Spencer Tracy: A Biography. By James Curtis. Alfred A. Knopf, 2011, 1,001 pp. $39.95

Spencer Tracy: A Biography. By James Curtis. Alfred A. Knopf, 2011, 1,001 pp. $39.95

He’s the kind of actor who makes it look so easy and you think to yourself, I can do that. Go ahead and try it. It’s not easy and you can’t do it.

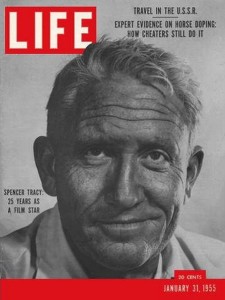

Spencer Tracy is widely considered to be the greatest film actor of the 20th century. Perhaps even the greatest actor of all time. Clark Gable considered him untouchable. “The guy`s good,” Gable famously said. “There`s nobody in the business who can touch him, and you`re a fool to try. And the bastard knows it, so don`t fall for that humble stuff!”

Having recently plowed through mammoth biographies of Lyndon Johnson and Walter Cronkite, two of the seminal figures in the second half of the twentieth century, I decided to complete the triumvirate by reading James Curtis’s recent biography of my favorite actor. At almost exactly 1,000 pages, it’s not a fast read, but it’s a wonderful journey.

I first encountered Spencer Tracy as a college senior at the University of Georgia in 1986. As a journalism major focusing on radio-TV-film production, I took the late great Barry Sherman’s class on journalism and broadcast history, and he challenged us to become familiar with the great movies and actors of the past, in the same way one reads “classic” books and authors to become more “well rounded.”

To help us along on that quest, he screened Citizen Kane in class, and before long I was haunting the student center theater for any classic movies that showed up. It was there that I first saw Casablanca and Gone With the Wind, both on the big screen. I was hooked.

Pretty soon I was wearing out my VCR, recording old movies on TBS and AMC (back when they showed old movies on either of those stations), anything that featured Humphrey Bogart and Clark Gable. Arsenic and Old Lace led me to Cary Grant, other movies to Henry Fonda, Jimmy Stewart, Edward G. Robinson, Gary Cooper, Errol Flynn, and Katharine Hepburn. I watched Alfred Hitchcock, John Ford, Preston Sturges, Ernst Lubitsch, and other directors. I bought a copy of Halliwell’s Filmgoer’s Companion and read it to tatters, all 1,200 pages.

James Cagney died that spring and I became interested in his work, watching and studying everything of his that I could find. Nobody then or now could dance like him, and when he was on screen, you couldn’t watch anybody else. As one critic wrote about Cagney, “He can’t even put a telephone receiver back on the hook without giving the action some special spark of life.”

James Cagney died that spring and I became interested in his work, watching and studying everything of his that I could find. Nobody then or now could dance like him, and when he was on screen, you couldn’t watch anybody else. As one critic wrote about Cagney, “He can’t even put a telephone receiver back on the hook without giving the action some special spark of life.”

About that time, PBS aired a documentary on Spencer Tracy. He was in a class all by himself. I had heard of him, of course, and was familiar with the names of some of his movies like Bad Day at Black Rock, but I’d never seen him on the screen. He was so good that he didn’t seem to be acting; as his fellow actors say, you never saw the mechanism at work. One reviewer watching him on stage in 1929, before he ever set foot in front of a camera, captured his style perfectly:

“No makeup—none to speak of—no tricks whatever; just an unassuming, easy manner that gets him about the stage without your quite knowing how he does it. He belongs to that school of acting—if it is a school—which doesn’t want you to think it is acting. It is acting, though, of a very high order, forceful, reserved, artistic.”

Tracy was born in Milwaukee in 1900, served in the Navy in World War I, and made his stage debut as a student at Ripon College in 1921. He attended the American Academy of Dramatic Arts (where he learned, he said, “the value of sincerity and simplicity, unembellished and unintellectualized”) and mastered his trade for 10 years in the daily grind of a stock company. The legendary George M. Cohan called him “the best goddamned actor I’ve ever seen.”

He hit it big on Broadway in 1930’s The Last Mile, and Fox Studios in Hollywood signed him to a contract that same year. He made his big screen debut in Up the River, directed by John Ford. Unlike most actors trained on the stage, Tracy was subdued, letting the camera come to him. It was inauspicious debut to the 75 films he would eventually make and that would establish him as the best screen actor in history, with nine Academy Award nominations and two Oscars for best actor.

He hit it big on Broadway in 1930’s The Last Mile, and Fox Studios in Hollywood signed him to a contract that same year. He made his big screen debut in Up the River, directed by John Ford. Unlike most actors trained on the stage, Tracy was subdued, letting the camera come to him. It was inauspicious debut to the 75 films he would eventually make and that would establish him as the best screen actor in history, with nine Academy Award nominations and two Oscars for best actor.

For all his acting talent, Tracy was the stereotypical “tortured” artist. He was as well known for his long-standing relationship with Katharine Hepburn, his moodiness, and his alcoholism as he was for his acting. After his first-born child, John, was born deaf, Tracy for the rest of his life blamed himself and his sins for his son’s affliction and it ate at him like a cancer. He suffered from chronic insomnia and took mouthfuls of pills just to catch an hour’s sleep. Tracy had multiple affairs with other actresses long before he met Hepburn—most notably Loretta Young and Ingrid Bergman–and his marriage to actress Louise Treadwell had settled into an awkward, platonic partnership by 1940.

Tracy and Hepburn first met filming Woman of the Year in 1942 and were together until his death 25 years later. I had always assumed it was an open secret, but Curtis tells us that was not the case. They were finally outed in several high-profile national magazines in the mid 1950s. Tracy had been married to Louise Treadwell since 1923, and they never divorced. After discovering their son John was deaf, Louise founded the John Tracy Clinic in Los Angeles and used her celebrity status to ensure its eventual success. Tracy’s staunch Catholicism and Louise’s insistence on remaining Mrs. Spencer Tracy until her death combined to keep them in a relationship that was unusual even in Hollywood. Despite their estrangement, they were still married at Spencer’s death in 1967, still respected each other, valued the other’s advice, and maintained a semblance of family with their two children. Curtis deftly details the finer points of their shared and singular history.

Tracy and Hepburn first met filming Woman of the Year in 1942 and were together until his death 25 years later. I had always assumed it was an open secret, but Curtis tells us that was not the case. They were finally outed in several high-profile national magazines in the mid 1950s. Tracy had been married to Louise Treadwell since 1923, and they never divorced. After discovering their son John was deaf, Louise founded the John Tracy Clinic in Los Angeles and used her celebrity status to ensure its eventual success. Tracy’s staunch Catholicism and Louise’s insistence on remaining Mrs. Spencer Tracy until her death combined to keep them in a relationship that was unusual even in Hollywood. Despite their estrangement, they were still married at Spencer’s death in 1967, still respected each other, valued the other’s advice, and maintained a semblance of family with their two children. Curtis deftly details the finer points of their shared and singular history.

Hepburn’s attraction to Tracy was immediate and intense. But what did Tracy see in Hepburn? We’re never quite sure, and Curtis lets the reader fill in the blanks on this particular subject. According to Hepburn, she never knew exactly how he felt about her. That he loved her is beyond doubt, but he apparently never told her, which is hard to believe. They appear to have been intellectually suited and admired each other’s acting ability enormously. They were undoubtedly lovers, though one wonders how much that ever entered into the equation, as Tracy was 42 when he met Hepburn and looked and acted 10 years older. She helped him through his insomnia and alcoholism, though the evidence points to the inescapable fact that he physically abused her on more than one occasion. They didn’t share a home until the last 5 years of his life; “I love him but I can’t live with him and he won’t live with Louise,” Hepburn said. In the end, it’s clear they were best friends, in the truest sense of those words, and enjoyed each other’s company and companionship. They made each other contented and happy.

At least as happy as anyone like Tracy could ever be. Alcoholism nearly ruined him. Several times in his career he would go on 10-day benders and wind up in hospital detox centers, bringing to a screeching halt whatever picture he might be working on or about to start, holding up production and costing the studio millions. His father and grandfather were alcoholics, and his working-class Irish Catholic upbringing in Milwaukee did nothi ng to dissuade him from seeking solace in a bottle. He went through long periods of sobriety, most notably after meeting Hepburn, but never really sought professional help. Alcoholism was more often seen as a moral failing than a disease during his life, a view to which both Hepburn and Tracy partially subscribed. He eventually brought it under control himself, though he never fully mastered it. He would go on and fall off the wagon with excruciating regularity all of his life.

ng to dissuade him from seeking solace in a bottle. He went through long periods of sobriety, most notably after meeting Hepburn, but never really sought professional help. Alcoholism was more often seen as a moral failing than a disease during his life, a view to which both Hepburn and Tracy partially subscribed. He eventually brought it under control himself, though he never fully mastered it. He would go on and fall off the wagon with excruciating regularity all of his life.

Curtis chronicles all of this in wonderful detail, but the heart of the story—as in Tracy’s life—was his work before the camera. Tracy labored in obscurity at Fox Studios through 5 years and 19 films before moving over to MGM and stardom in 1935. If you’ve never seen him on screen, go on Netflix right now and queue up any one of a dozen of his best pictures: Inherit the Wind (widely acclaimed as his best work), Judgment at Nuremburg, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, Father of the Bride, Boy’s Town, Fury (his 1936 break-out role), Captains Courageous, San Francisco, The Old Man and the Sea, Bad Day at Black Rock.

In my opinion all nine of his movies with Katharine Hepburn are good but especially watch Woman of the Year, Keeper of the Flame, State of the Union, Adam’s Rib, Pat and Mike, and Desk Set. The latter movie is little regarded among movie critics, but two scenes in it are worth studying in some detail: when Tracy quizzes Hepburn about her memory over lunch on t he rooftop of their office building, and later when Tracy gets caught in the rain on the way home and Hepburn invites him in for dinner. Both scenes feature two movie legends at the top of their game, with a natural affinity for their work and for each other that comes through brilliantly on screen. I particularly like him in Stanley Kramer’s It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, because he’s as superb a comedian as anyone else in that picture. Bottom line: if he’s in it, watch it. You will never be disappointed.

he rooftop of their office building, and later when Tracy gets caught in the rain on the way home and Hepburn invites him in for dinner. Both scenes feature two movie legends at the top of their game, with a natural affinity for their work and for each other that comes through brilliantly on screen. I particularly like him in Stanley Kramer’s It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, because he’s as superb a comedian as anyone else in that picture. Bottom line: if he’s in it, watch it. You will never be disappointed.

There are many actors, then and now, who never convince you they’ve done anything more than memorize lines and pretend to be someone else. For all their matinee idol appeal, I’ve always felt this way about Brad Pitt and Tom Cruise; you can tell they’re performing. Even some of Hollywood’s greatest legends, like Clark Gable, John Wayne, Gary Cooper, and Errol Flynn, were always accused of just playing themselves, that they weren’t really actors. As John Wayne famously said, “I don’t act, I react.” (Tracy once told the Duke, “It’s a good thing you’re so good looking, because you can’t act your way out of a paper bag.” Of Gable, whom he loved, he said, “Can’t act, doesn’t care, and everybody loves him better than any actor that was ever born.”)

Tracy, as one critic wrote, did not act, he was. It never seemed as if he was trying to perform. He belonged to a school of acting “which believed in selection—not how much the actor could do in any given scene, but how little he had to do to make the point, using the minimum to make the maximum.” Tracy understood the power of silence, of scarcely moving; it was all in his eyes and face, and the way he held himself. As Curtis writes, he demanded the audience’s attention in a natural and subdued way, dared them not to feel what he was feeling, not to think what he was thinking. To my mind, Tom Hanks is the living embodiment of Spencer Tracy: they both underplay to enormous effect what others would turn into farce.

How did he do it? What was his technique? No one really knows, because he never really shared his secret, a legacy, perhaps of his days working as a magician as a boy. Gene Kelly, who starred with Fredric March and Tracy in Inherit the Wind, described it thus: “I could understand and see what March was doing. He was like Olivier. A wonderful technician. You could see the characterization taking shape—the cogs and wheels beginning to turn. If you studied his methods closely, it was all there, like an open book. But with Spence it was just the reverse. He’d play a scene with you, and you’d think nothing much was happening. Then, when you saw the rushes, there it all was—pouring out of his face. He was quite amazing. The embodiment of the art that conceals art. It was impossible to learn anything from Spence, because everything he did came from some inner part of himself, which to an outsider anxious to learn, was totally inaccessible. All you could do was watch the magic and be amazed.”

Part of it, of course, was his natural talent and ability. When other actors asked him for advice, he would invariably reply, “There’s nothing I can teach you. Your either are an actor, or you’re not. And you are.” But though he made it seem effortless, it wasn’t. He did have a photographic memory, a gift for any actor, but he worked hard at making it seem as though he wasn’t doing anything at all. He spent long hours alone in his room at night preparing himself for the next day’s work.

Watch him read the verdict in Judgment at Nuremburg (over 10 minutes, done in one take): “Before the people of the world . . . let it now be noted . . . that here in our decision, this is what  we stand for: Justice, truth, and the value of a single human being”; watch him cross examine Fredric March in Inherit the Wind, or give the final speech in Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner: “Old? Yes, Burnt out? Certainly. But I can tell you the memories are still there—clear, intact, in destructible. And they’ll still be there if I live to be a hundred and ten.” A cough here, a lowering of his voice mid-sentence there, a catch in his throat as he described his love for Christina (Hepburn): Small, subtle things, that make his performances seem wholly natural, but nearly impossible to replicate. As Stanley Kramer, who directed all three movies, said: “Tracy reduced everything to a fine powder of simplicity, and that takes hard work, it takes a lot of hard work. ‘Improvisation,’ Tracy always said, ‘is perspiration.’”

we stand for: Justice, truth, and the value of a single human being”; watch him cross examine Fredric March in Inherit the Wind, or give the final speech in Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner: “Old? Yes, Burnt out? Certainly. But I can tell you the memories are still there—clear, intact, in destructible. And they’ll still be there if I live to be a hundred and ten.” A cough here, a lowering of his voice mid-sentence there, a catch in his throat as he described his love for Christina (Hepburn): Small, subtle things, that make his performances seem wholly natural, but nearly impossible to replicate. As Stanley Kramer, who directed all three movies, said: “Tracy reduced everything to a fine powder of simplicity, and that takes hard work, it takes a lot of hard work. ‘Improvisation,’ Tracy always said, ‘is perspiration.’”

It wasn’t unusual for his fellow cast and crew to burst into applause after one of his scenes. Fellow actors on the set or movie lot would stand offstage just to watch him work. The three movies cited above contain his best work, superb, flawless performances. If I ever aspired to act, I would study them until my eyes blurred. Burt Lancaster, following the verdict scene in Judgment at Nuremburg, asked Tracy, “How did you do that so easily?” Tracy quietly replied, “You practice for 35 years.” The art that conceals art, using the minimum to make the maximum. There was nobody better.

I just finished reading your podcast on James Curtis’ biography of Spencer Tracy. I have read the biography, also, as well as anything else I’ve been able to put my hands on in the last 7 months. I especially like the way you phrased Spencer and Louise’s relationship, ‘ an awkward, platonic partnership’.

Pingback: Blog on Blog | History@UF

Pingback: oakley homme pas cher

Pingback: nike tn requin pas cher

Pingback: nike air max pas cher

Pingback: maglie italia mondiali 2014

Pingback: scarpe hogan outlet

Pingback: louboutin sale

Pingback: Nike Air Max 1 Essential Chaussure pour Homme

Pingback: eso gold

Pingback: christian louboutin prix

Pingback: portefeuille homme longchamp

Pingback: ray ban frames

Pingback: 皇冠足球盘口分析

Pingback: 必博备用网址

Pingback: ferragamo outlet

Pingback: nike outlet

Pingback: jordan shoes for sale

Pingback: prada outlet

Pingback: グッチ バッグ

Pingback: coach factory online

Pingback: buy fifa coins

Pingback: Elderscrollsnet.com

Pingback: EASPORTS

Pingback: bayern trikot

Pingback: maillot france coupe du monde 2014

Pingback: fifa 14