Cronkite. By Douglas Brinkley. Harper Collins, 2012, 819 pp., $35.

Cronkite. By Douglas Brinkley. Harper Collins, 2012, 819 pp., $35.

“From Dallas, Texas, the flash, apparently official, President Kennedy died at 1 o’clock p.m., Central Standard Time, 2 o’clock, Eastern Standard Time, some thirty-eight minutes ago.”

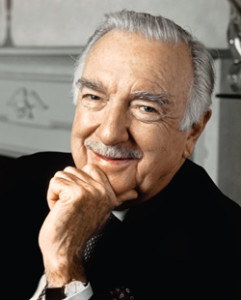

Last week I wrote about the 50th anniversary of the JFK assassination that America commemorated last November. Among all the moments that linger from that day in Dallas, there is another iconic image that has entered into our collective historical consciousness: that of Walter Cronkite sitting at his anchor desk at the CBS studios in New York, overcome with emotion as he announced President’s Kennedy’s death to a shocked and startled nation. Cronkite taking off his glasses and blinking back tears remains for an entire generation one of the most-remembered moments from that awful day and one of the most famous pieces of television theater in the history of the medium. (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RE-TCzIHrLI)

I magine now to find out that “Uncle Walter” staged the whole bit with the glasses, as Douglas Brinkley tells us in this new biography of the broadcasting legend. November 22, 1963, cemented Cronkite as presiding media king of America’s booming television empire. He metaphorically held the nation’s hand during those four excruciating days through Kennedy’s funeral, and when it was all over he was on his way to becoming the “Most Trusted Man in America.”

magine now to find out that “Uncle Walter” staged the whole bit with the glasses, as Douglas Brinkley tells us in this new biography of the broadcasting legend. November 22, 1963, cemented Cronkite as presiding media king of America’s booming television empire. He metaphorically held the nation’s hand during those four excruciating days through Kennedy’s funeral, and when it was all over he was on his way to becoming the “Most Trusted Man in America.”

It’s hard now, given all the television, satellite, cable, and internet viewing choices we have and the proliferation of social media, to remember or appreciate what it was like for millions of Americans to turn on their TVs each evening and invite the anchormen at the Big Three into their dinner hours. Chet Huntley and David Brinkley ruled on NBC (and beat Cronkite in the ratings till 1967), with Howard K. Smith and later Harry Reasoner at ABC. Even when I was in journalism school at the University of Georgia in the mid-1980s, the mantra was “hear it now [radio], see it tonight [TV], read it tomorrow [newspapers].” First CNN, then the internet and now the smart phone have made all of that obsolete.

But in post-World War II America, no one was more trusted or relied upon to tell Americans “that’s the way it was,” and for many Baby Boomers, Walter Cronkite was America. From the launch of the Telstar satellite, through Sputnik, JFK’s assassination, the moon landing, the Vietnam War, and Watergate, no other media figure commanded the authority or the trust that Cronkite did as CBS reporter from the mid-1950s and as anchor of the CBS Evening News from 1962 to 1981.

But in post-World War II America, no one was more trusted or relied upon to tell Americans “that’s the way it was,” and for many Baby Boomers, Walter Cronkite was America. From the launch of the Telstar satellite, through Sputnik, JFK’s assassination, the moon landing, the Vietnam War, and Watergate, no other media figure commanded the authority or the trust that Cronkite did as CBS reporter from the mid-1950s and as anchor of the CBS Evening News from 1962 to 1981.

For those of us who grew up in the 1960s and 70s, this book is chock full of the faces and voices we all knew and loved: Cronkite, Roger Mudd, Eric Severeid, Douglas Edwards, Charles Collingwood, Chet Huntley, David Brinkley, Tom Brokaw, Dan Rather, Connie Chung, Leslie Stahl, Bernard Shaw, Barbara Walters, Charles Kuralt, Andy Rooney, right up to Brian Williams, the current NBC News anchor who revered Uncle Walter and had a special relationship with him. For an old news junkie like me this book was a feast.

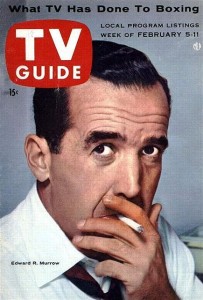

Brinkley details Cronkite’s rise from Kansas City and United Presser scribe through World War II to the top of the media mountain as the revered CBS newsman. Most interesting to me was his volatile relationship with the legendary Edward R. Murrow and his later fierce competition for interviews with Barbara Walters at ABC, whom he did not at first take seriously.

Brinkley details Cronkite’s rise from Kansas City and United Presser scribe through World War II to the top of the media mountain as the revered CBS newsman. Most interesting to me was his volatile relationship with the legendary Edward R. Murrow and his later fierce competition for interviews with Barbara Walters at ABC, whom he did not at first take seriously.

Cronkite hadn’t been one of Murrow’s Boys during World War II, and the fiercely competitive and territorial Cronkite was never beholden to Murrow once he went to work at CBS. Murrow was good on CBS specials with a script and the ever-present cigarette in his hand, exposing Joseph McCarthy or some other corrupt politician, but Cronkite was better on the fly, as he proved repeatedly at political conventions, NASA rocket launchings, and especially on the day of Kennedy’s assassination. No one was smoother, more relaxed, or more reassuring than Walter Cronkite in a crisis. When he finally denounced the Vietnam War as a stalemate in 1968 following the Tet Offensive, LBJ knew he had lost middle America.

For Cronkite, Barbara Walters heralded the  advent of “entertainment as news” and he scoffed at the notion that she was serving the public’s interest or practicing serious journalism. He refused to take her seriously until she repeatedly got the big story, leaving Cronkite sputtering that this glamorous upstart had scooped him once again.

advent of “entertainment as news” and he scoffed at the notion that she was serving the public’s interest or practicing serious journalism. He refused to take her seriously until she repeatedly got the big story, leaving Cronkite sputtering that this glamorous upstart had scooped him once again.

For all his on-air good manners and avuncular nature, Cronkite was fiercely competitive and never hesitated to go for the jugular when his territory or ego was involved. He deplored Dan Rather’s work in the anchor chair after succeeding Cronkite on the CBS Evening News and never missed an opportunity to blister Rather’s performance in public, particularly after Rather’s spectacular fall from grace at CBS. Brinkley says that Rather was the only man whom Cronkite despised, and the one person he would not mend fences with before he died.

Cronkite lived long enough to see not only entertainment become news, but also the advent of reality TV, Twitter, Facebook, and an entire generation that confuses fame with real accomplishment. We are now all velocity and no coherence, and it will only get worse. But before we descend completely into curmudgeonly-ness, a la Cronkite in his dotage, we must remember that for young people coming of age now, this will eventually be “the good old days.” Context is everything.

As Brinkley points out, when so much of American culture is disposable, Cronkite and his work endures. Anchors will come and go, but there will be only one Uncle Walter, the one guy in TV, who, as Ted Turner noted, nobody ever got sick of. We seem now to long for his brand of authenticity, his pride of professionalism, his sense of moderation. The American public sensed what fellow sailor Mike Ashford said at his funeral: when people asked him what Cronkite was really like, his answer was always “He’s just the way you hope he is.”

As Brinkley points out, when so much of American culture is disposable, Cronkite and his work endures. Anchors will come and go, but there will be only one Uncle Walter, the one guy in TV, who, as Ted Turner noted, nobody ever got sick of. We seem now to long for his brand of authenticity, his pride of professionalism, his sense of moderation. The American public sensed what fellow sailor Mike Ashford said at his funeral: when people asked him what Cronkite was really like, his answer was always “He’s just the way you hope he is.”

When those moments of collective shock come—assassinations, Watergate, the Challenger explosion, September 11—we still turn to the media, splintered and fragmented though it may be now, to help us understand it and to share our grief with each other. And as long as America remembers that tragic autumn day in Dallas, we’ll also remember that singular moment when Walter Cronkite cemented his position as national father-figure-in-chief.

When those moments of collective shock come—assassinations, Watergate, the Challenger explosion, September 11—we still turn to the media, splintered and fragmented though it may be now, to help us understand it and to share our grief with each other. And as long as America remembers that tragic autumn day in Dallas, we’ll also remember that singular moment when Walter Cronkite cemented his position as national father-figure-in-chief.

And that’s the way it is, Wednesday, February 5, 2014. For GHS, I’m Stan Deaton. Thanks for reading.

Pingback: Juicy Couture Outlet

Pingback: Tiffany & Co Bracelets Three Letters Lock