Van Wyck Brooks, The World of Washington Irving (E.P. Dutton, 1944, 387 pp.)

Van Wyck Brooks, The World of Washington Irving (E.P. Dutton, 1944, 387 pp.)

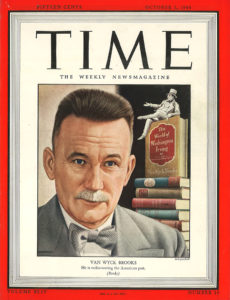

Van Wyck Brooks is an author whose work was enormously popular in the mid-20th century. How popular? Walk into any used bookstore and you’ll trip over his books. Time magazine, whose cover he graced in 1944, called him “the nation’s most distinguished literary critic.”

He is most famous for five volumes known collectively as “Makers and Finders: A History of the Writer in America, 1800-1915,” the most well-known of which is The Flowering of New England, 1815-1865, published in 1936, winner of the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award. The other volumes are New England: Indian Summer, 1865-1915 (1940); The World of Washington Irving (1944); The Times of Melville and Whitman (1947); and The Confident Years: 1885-1915 (1952).

Scott Berg’s Max Perkins: Editor of Genius (1978) recounts the harrowing years when Brooks was unable to write because of a mental breakdown, and how Perkins helped him climb back out of his psychic abyss to become one of the 20th century’s most prolific, if now forgotten, authors. Brooks himself was the focus of Raymond Nelson’s Van Wyck Brooks: A Writer’s Life (1981), and his long friendship with critic Lewis Mumford was detailed in Robert E. Spiller’s edited volume of their letters, The Record of a Literary Friendship, 1921-1963 (1970).

I am thoroughly enjoying The World of Washington Irving, being a huge fan of Irving, but the book’s canvas stretches far beyond, covering a host of other writers from Edgar Allen Poe to James Fenimore Cooper, John James Audubon, William Gilmore Simms, and lesser luminaries whose stars have long since dimmed. There is a treasury of learning here, and it is a pleasure to read.

Van Wyck (rhymes with bike) Brooks was widely lauded during his own day with awards and honorary degrees, but as Patton so rightly noted, all glory is fleeting. When Brooks died in Bridgewater, Connecticut in 1963 at the age of 77, his town decided to build a library wing in his honor. The effort died after ten years of meager fundraising, only to be revived when a California hermit who admired Brooks’s writing left the library $300,000 in his will. The wing was finally dedicated in 1980.

Eighty years ago, with the Nazis rising in Europe and with the world tottering on the brink of madness, critic Malcolm Cowley reviewed The Flowering of New England. In addition to Brooks’s erudition and scholarship, Cowley lauded Brooks for “turning back to the great past in order to see the real nature of the traditions that we are trying to save, and in order to gain new strength for the struggles ahead.”

Gaining new strengths for the struggles ahead, be they against personal demons or the next global firestorm: still one of the best reasons I’ve ever heard for reading books like this, then or now.