Former baseball commissioner and Yale president Bart Giamatti captured it best: Baseball, he wrote, breaks your heart: “It is designed to break your heart. The game begins in the spring, when everything else begins again, and it blossoms in the summer, filling the afternoons and evenings, and then as soon as the chill rains come, it stops and leaves you to face the fall all alone. You count on it, rely on it to buffer the passage of time, to keep the memory of sunshine and high skies alive, and then just when the days are all twilight, when you need it most, it stops.”

Former baseball commissioner and Yale president Bart Giamatti captured it best: Baseball, he wrote, breaks your heart: “It is designed to break your heart. The game begins in the spring, when everything else begins again, and it blossoms in the summer, filling the afternoons and evenings, and then as soon as the chill rains come, it stops and leaves you to face the fall all alone. You count on it, rely on it to buffer the passage of time, to keep the memory of sunshine and high skies alive, and then just when the days are all twilight, when you need it most, it stops.”

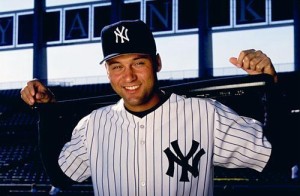

As a lifelong baseball fan, I’ve always hated to see the season end. Unless the Braves makes the playoffs, that is, which they didn’t this year, after another awful September. I love playoff season too, but this year is different. The end of the season marked the end of Derek Jeter’s career.

Before you Braves and Red Sox fans fill up my inbox with flaming burritos in protest, let me explain. I’ve never been much of a Yankee fan. Indeed, it’s still hard for me to accept the outcome of the 1996 World Series. The Braves, defending World Series champions that year, again won the National League pennant in ’96 and went to New York to open the series with the Yankees.

Before you Braves and Red Sox fans fill up my inbox with flaming burritos in protest, let me explain. I’ve never been much of a Yankee fan. Indeed, it’s still hard for me to accept the outcome of the 1996 World Series. The Braves, defending World Series champions that year, again won the National League pennant in ’96 and went to New York to open the series with the Yankees.

They promptly shocked the baseball world by winning the first two games in Yankee Stadium by a combined score of 16-1 behind the offensive firepower of Andruw Jones and Fred “Crimedog” McGriff and the dazzling pitching duo of John Smoltz and Greg Maddux. The next three games would be in Atlanta, followed by two more in New York if necessary. The Braves needed to win only two of those potential five games to clinch their second consecutive series. It was going to be Atlanta Braves baseball nirvana.

Except it never happened, of course. They lost the next four games and that was that, with the Yankees winning their first championship since 1978. Derek Jeter was on that ’96 team, playing in his first full season as a Yankee. The Braves lost to Jeter’s Yankees again in 1999.

So though I’ve never been a dyed-in-the-wool Yankee hater, I’ve not been partial to them either, as we say. But I can certainly respect the history of the great franchise and the great players who’ve worn the pinstripes—Ruth, Gehrig, DiMaggio, Mantle, Jackson, Mattingly, Rivera.

None, however, were ever better than number 2, who retired Sunday after 20 years in the big leagues. It was all in the way he played the game.

Baseball is a game of numbers, but it wasn’t just Jeter’s statistics that made him great, though they’re impressive enough too. One of the reasons I love baseball is that it’s so tied to its own history, as no other sport really is—every player who puts on the uniform is compared to all of those who have gone before. When Jeter legged out a single on Sunday for his last hit, it was number 3,465 in his career. Only five players in major-league history, across more than 145 years, have ever hit more. Only five. He finished with a .310 batting average, won five World Series titles, five Gold Gloves, five Silver Slugger awards, and was an All-Star fourteen times. He will be voted unanimously into the Hall of Fame.

Baseball is a game of numbers, but it wasn’t just Jeter’s statistics that made him great, though they’re impressive enough too. One of the reasons I love baseball is that it’s so tied to its own history, as no other sport really is—every player who puts on the uniform is compared to all of those who have gone before. When Jeter legged out a single on Sunday for his last hit, it was number 3,465 in his career. Only five players in major-league history, across more than 145 years, have ever hit more. Only five. He finished with a .310 batting average, won five World Series titles, five Gold Gloves, five Silver Slugger awards, and was an All-Star fourteen times. He will be voted unanimously into the Hall of Fame.

In this, his last season, he played in 145 games. Only one other Hall of Famer in the last century, Al Kaline, played in more games in his final season. His walk-off game-winning single in his last game at Yankee Stadium on September 25 was the stuff of legend. And he played all twenty seasons with the same team, again a rare thing.

But the most impressive statistic about Derek Jeter to me? Zero. Across twenty major-league seasons, he was never ejected from a game. Not once. With my temper I would have rivaled Bobby Cox’s record for getting tossed out of games (158) if I’d ever been so blessed to play that long, so I can appreciate Jeter’s self-control perhaps more than anything. To play at that high level and never lose your cool enough to get thrown out of a game is remarkable indeed. It speaks to his character, his temperament under pressure, and yes, his upbringing too.

But the most impressive statistic about Derek Jeter to me? Zero. Across twenty major-league seasons, he was never ejected from a game. Not once. With my temper I would have rivaled Bobby Cox’s record for getting tossed out of games (158) if I’d ever been so blessed to play that long, so I can appreciate Jeter’s self-control perhaps more than anything. To play at that high level and never lose your cool enough to get thrown out of a game is remarkable indeed. It speaks to his character, his temperament under pressure, and yes, his upbringing too.

True to the best about the sport, baseball history was in play on his final day in uniform, last Sunday, September 28, in Boston. With two hits on Sunday, Jeter could have tied Ty Cobb’s record for the most seasons with at least 150 hits, with 18.The Georgia Peach played his last season in 1928, 86 years ago, so this is a cumulative record that speaks to skill and longevity, one not likely to fall very easily. Yankee manager Joe Girardi told Jeter about the record on Sunday morning, and asked if he wanted to play longer than his planned two at bats. Jeter said no. He would stick with just two trips to the plate and take the results, whatever they were.

“I never played the game for numbers,” he said. “So why start now?” He fell one hit short.

“I never played the game for numbers,” he said. “So why start now?” He fell one hit short.

Others have more eloquently described Jeter’s career than I can, but as a lifelong fan of the national pastime, I know something rare when I see it. I’ve been lucky enough in my life to see some great baseball players in person. Long-suffering readers of this blog will recall that I saw Hank Aaron hit homerun number 713 in 1973. I saw the Big Red Machine in a championship year, and many other legendary players too numerous to mention across 40 years of attending big-league games.

Jeter played the game the way it’s supposed to be played, the way we all dreamed of back when we were playing ball with our friends out in the street or in the backyard, when we played just for the sheer love of the game. Jeter played that way every day.

He played with an intensity that Pete Rose had, but without Rose’s arrogance. He played with unbelievable skill—no one will ever forget his famous flip in the 2001 playoffs against the A’s—with finesse, style, and above all, with class, both on and off the field. He didn’t run his mouth or think he was entitled, or create more headlines for what he did off the field than on. He respected the game and played it with honor.

How remarkable was he? As I mentioned above, he played his last game in Boston, home of the Red Sox, the Yankees’ most hated rival, and the fans stood and cheered for him as if he were their own, long and loudly and with tears in their eyes. Red Sox greats from years past lined up to shake his hand. Boston’s a great baseball town, and they know a legend when they see one, but even this was something to see. It would be like UGA fans giving a retiring Steve Spurrier a standing and rousing ovation, if Spurrier had ever had one ounce of class.

How remarkable was he? As I mentioned above, he played his last game in Boston, home of the Red Sox, the Yankees’ most hated rival, and the fans stood and cheered for him as if he were their own, long and loudly and with tears in their eyes. Red Sox greats from years past lined up to shake his hand. Boston’s a great baseball town, and they know a legend when they see one, but even this was something to see. It would be like UGA fans giving a retiring Steve Spurrier a standing and rousing ovation, if Spurrier had ever had one ounce of class.

Will we see his like again? Yes. One thing we know about baseball is that it renews itself, and as one era ends, another begins, even if it takes a few years to realize it. When Jeter came on the scene in the 1995 season, another Yankee legend—Don Mattingly—was ending his storied career. Donnie Baseball, now the Dodgers’ manager, played all 14 of his big-league seasons with the Yankees and retired with a career .307 average, one year before the Yankees began their championship run. It was the end of an era, but without our even knowing it at the time, a new one began that same season. It’s the way the game is played.

To watch a great athlete across his entire career is one of the great joys in life. To then see him walk away in the fading twilight is a reminder of our own fleeting youth, when we played the game with passion and love, and of our own mortality. It is a painful reminder, if we needed one, that all good things must end someday.

So there is no joy in Mudville at the end of this season and the end of Derek Jeter’s splendid career. To paraphrase John Fogerty, this particular brown-eyed handsome man has rounded third for the last time. Like all great players who have gone before, Jeter will now gracefully stand aside and make way for others whose names we may not know very well—yet—but who will, in time, achieve greatness. They’ll be here as sure as one season follows another, keeping the memory of high skies, sunshine, and childhood alive. In another September we’ll lament they’re passing from the stage as well. It’ll break our hearts because baseball always does. It’s the way the game is played.

So there is no joy in Mudville at the end of this season and the end of Derek Jeter’s splendid career. To paraphrase John Fogerty, this particular brown-eyed handsome man has rounded third for the last time. Like all great players who have gone before, Jeter will now gracefully stand aside and make way for others whose names we may not know very well—yet—but who will, in time, achieve greatness. They’ll be here as sure as one season follows another, keeping the memory of high skies, sunshine, and childhood alive. In another September we’ll lament they’re passing from the stage as well. It’ll break our hearts because baseball always does. It’s the way the game is played.