A recent story on the national park at the site of the crash of Flight 93 in Shanksville, Pennsylvania, brought back all the raw emotions of September 11. The anger, the terror, and the realization that our lives can change in an instant was never more starkly on display than on that sun-lit Tuesday fifteen years ago.

A recent story on the national park at the site of the crash of Flight 93 in Shanksville, Pennsylvania, brought back all the raw emotions of September 11. The anger, the terror, and the realization that our lives can change in an instant was never more starkly on display than on that sun-lit Tuesday fifteen years ago.

There will be many moments of reflection on this momentous anniversary. As we do, we should reflect on two other events from this past July that went by virtually unnoticed.

July 1 marked the 100th anniversary of the beginning of the Battle of the Somme during World War I. On July 2, Elie Wiesel died at age 87, the Auschwitz survivor who spoke eloquently for those 6 million who could no longer speak for themselves.

What will happen when those who give voice to hell in the flesh are gone?

At the anniversary of September 11, it’s worth remembering that every event in history that evoked raw emotions was in time smoothed over and faded from memory. In our own time, the Somme and Wiesel’s death should remind us what can happen when the voices of resentment become dominant.

We’ve already forgotten about the horrors of the Somme—and World War I in general. Probably not one American on the street could tell you what happened in that murderous and savage battle. Or at Passchendaele or Verdun.

not one American on the street could tell you what happened in that murderous and savage battle. Or at Passchendaele or Verdun.

The Somme is a river in northern France, and the battle that took place there for 136 days in 1916 has become a metaphor for the useless slaughter of human life.

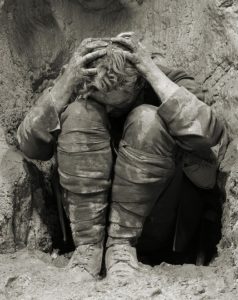

The Germans were securely entrenched and strategically located when the allied British and French forces launched their frontal attack on a 21-mile front north of the River. Before they sent the men over the top, they shelled the dug-in Germans with a week-long artillery bombardment. For the Germans living through it, it was hell: A soldier who suffered through the bombardment at Verdun said that by day nine almost every soldier was crying. The bombardment was so loud and so intense it could be heard north of London. When the shells subsided for an instant, the air was filled with the buzzing of millions of flies who were eating the dead, and the terrifying high-pitched screams of the rats who often grew so big and bloated from feeding on the dead, it was said that they would attack and eat a wounded man if he couldn’t defend himself. It brought catatonic depression, shell shock, madness.

Saturday, July 1, 1916, was the day of the biggest military fiasco in British history. At 7:30 that morning Field Marshal Douglas Haig, the commander of the British Expeditionary Force, ordered his men over the top, out of their trenches, to attack the German lines head on at the Somme. Within a matter of hours 21,000 British soldiers were killed, 40,000 wounded, many of them within sight of their own trenches.

By noon 60,000 men lay wounded, dying, or dead. Let that soak in. 60,000. The Germans said they didn’t even have to aim, just shoot. The 1st Newfoundland Battalion lost 91% of its men within 40 minutes, which is why July 1 is Memorial Day in Newfoundland and Labrador.

By noon 60,000 men lay wounded, dying, or dead. Let that soak in. 60,000. The Germans said they didn’t even have to aim, just shoot. The 1st Newfoundland Battalion lost 91% of its men within 40 minutes, which is why July 1 is Memorial Day in Newfoundland and Labrador.

After that day, the Somme offensive deteriorated into a battle of attrition. In October torrential rains turned the battlefield into an impassable sea of mud, and by mid-November the Allies had advanced only 5 miles.

Between July and November 1916, there were an estimated 1.3 million Allied and German casualties on the Somme. Among the British losses 73,412 were never recovered or identified.

Let me repeat those figures: 1.3. million casualties in that one battle in a war that lasted over four years. Almost 75,000 missing. To give you some perspective, as of March 23, 2016, the total of those missing in action in Vietnam is 1,621.

All those deaths and mangled bodies, for what? A few yards of mud. Almost no one today can tell you anything about it, or explain how the war began in a toxic brew of ethnic hatred, religious animosities, and tribalistic territorial alliances.

The poison of the first world war culminated of course in the second one.

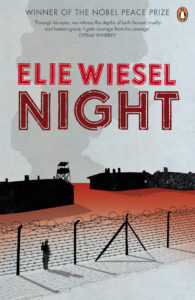

In 1956, Elie Wiesel published Night, his memoirs of his experience in the concentration camps: “Never shall I forget that night, the first night in camp, which has turned my life into one long night. Never shall I forget that smoke. Never shall I forget the little faces of the children, whose bodies I saw turned into wreaths of smoke beneath a silent blue sky. Never shall I forget these things, even if I am condemned to live as long as God himself. Never.”

In 1956, Elie Wiesel published Night, his memoirs of his experience in the concentration camps: “Never shall I forget that night, the first night in camp, which has turned my life into one long night. Never shall I forget that smoke. Never shall I forget the little faces of the children, whose bodies I saw turned into wreaths of smoke beneath a silent blue sky. Never shall I forget these things, even if I am condemned to live as long as God himself. Never.”

Wiesel recounted it all, including the murders of his father, mother, and sister.

The U.S. Third Army liberated Buchenwald on April 11, 1945. Among the survivors was Elie Wiesel.

“I must do something with my life,” he said years later. “It is too serious to play games with anymore, because in my place, someone else could have been saved. And so I speak for that person.”

The Somme and the Holocaust stand as warnings as we once again find ourselves grappling both at home and around the world with tribalism, revanchism, and nativism. We delude ourselves if we think these things cannot happen again.

The European Union has presided over peace in Europe for the longest period in its history, 71 years and counting, and it is imploding before our eyes in a swirl of economic unrest and ethnic hostility. We think that we are too superior to blunder blindly into another useless and forgotten conflict like World War I, leaving 37 million causalities behind. We are not.

We think we would never allow something like the Holocaust to happen again, that we would see the madmen coming and cut them down before they turned the world into a charnel house again. Would we? Emotions flamed by legitimate fears of terrorism and fueled by religious and ethnic hatred raise troubling doubts.

We think we would never allow something like the Holocaust to happen again, that we would see the madmen coming and cut them down before they turned the world into a charnel house again. Would we? Emotions flamed by legitimate fears of terrorism and fueled by religious and ethnic hatred raise troubling doubts.

This September 11, along with the memory of our dead and the brave warriors who have since died fighting, remember too the dead of the Somme and the unchecked madness that allowed 6 million to be exterminated. The cult of resentment and fanaticism have their fatal and tragic consequences. Night may come again. If it does, humanity itself will be its author—and its final victim.

Elie Wiesel warned that “if we forget, we are guilty, we are accomplices.” 37 million casualties in World War I. Over 100 million in World War II. 6 million human beings in the Holocaust. Fifteen years after September 11 and every day forward, remember.

Elie Wiesel warned that “if we forget, we are guilty, we are accomplices.” 37 million casualties in World War I. Over 100 million in World War II. 6 million human beings in the Holocaust. Fifteen years after September 11 and every day forward, remember.

Remember.