Teaching is not a lost art, but the regard for it is a lost tradition–Jacques Barzun

Teaching is not a lost art, but the regard for it is a lost tradition–Jacques Barzun

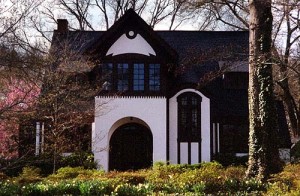

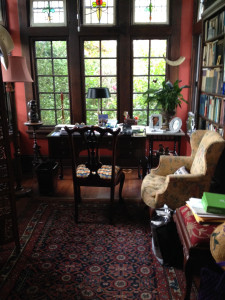

William Arthur Ward wrote that the mediocre teacher tells, the good teacher explains, the superior teacher demonstrates, the great teacher inspires. Carl Vipperman, my very first history professor at the University of Georgia, died on June 28, 2014, at the age of 86. I was honored and humbled to be the only one of the thousands of students he had in a 30-year teaching career to speak at his memorial service in Athens on July 2. I was privileged that day also to spend time with many of Carl’s friends and family, including his beloved wife Reggie, son Carl Jr.—known as Vip—and Vip’s wife Vick ie (all pictured below, left, at Vip’s 1982 wedding). I visited his beautiful Tudor-style historic home on W. Cloverhurst Avenue (at right), perused the book-lined shelves in his study, sat in his reading chair in the writing nook that he built in the backyard (reminiscent of writer Christopher Morley’s famous similar retreat, the Knothole), and walked the well-manicured grounds of Reggie’s beautiful gardens. Vip and I spent time in his father’s writing retreat that evening reminiscing over a glass of wine about his father and his own successful career as songwriter and musician. It was an emotional day of tribute to the good and gentle man who inspired me to choose the path of historian. Carl Jackson Vipperman was a great teacher, in the finest tradition of that honorabl

ie (all pictured below, left, at Vip’s 1982 wedding). I visited his beautiful Tudor-style historic home on W. Cloverhurst Avenue (at right), perused the book-lined shelves in his study, sat in his reading chair in the writing nook that he built in the backyard (reminiscent of writer Christopher Morley’s famous similar retreat, the Knothole), and walked the well-manicured grounds of Reggie’s beautiful gardens. Vip and I spent time in his father’s writing retreat that evening reminiscing over a glass of wine about his father and his own successful career as songwriter and musician. It was an emotional day of tribute to the good and gentle man who inspired me to choose the path of historian. Carl Jackson Vipperman was a great teacher, in the finest tradition of that honorabl e but too often undervalued profession. You will see why I was asked to speak in the remarks that follow, which I delivered at his memorial service:

e but too often undervalued profession. You will see why I was asked to speak in the remarks that follow, which I delivered at his memorial service:

“I begin with a quote from Charles Dickens, which is

fitting not only because of what it says, but also because Carl Vipperman could quote literature like few other people: ‘That was a memorable day to me, for it made great changes in me. But it is the same with any life. Imagine one selected day struck out of it, and think how different its course would have been. Pause you who read this, and think for a moment of the long chain of iron or gold, of thorns or flowers, that would never have bound you, but for the formation of the first link on one memorable day.’

One of those days for me was Friday, September 17, 1982, my first day of college and the day I first met Carl Vipperman. I was taking History 251, the first half of American history, in the PJ auditorium and was one of 300 people waiting for class to begin. In walked Carl Vipperman. He was silver haired (though only a little older than I am right now), wearing a white button-down oxford shirt, blue jeans, and comfortable brown shoes. Unassuming. He didn’t look like a professor so much as the guy you meet hanging out down at the  hardware store. There wasn’t much to go on, but I remember thinking that I might actually be able to do this college thing, and that I liked Carl Vipperman. I didn’t know it at the time, but that day was for me one like Dickens described, a memorable day that made great changes in me and bound me with chains of gold and flowers.

hardware store. There wasn’t much to go on, but I remember thinking that I might actually be able to do this college thing, and that I liked Carl Vipperman. I didn’t know it at the time, but that day was for me one like Dickens described, a memorable day that made great changes in me and bound me with chains of gold and flowers.

For the next 10 weeks, Monday through Friday, Carl walked up on stage and talked about American history. He started with the Norse invasion and it seemingly took him weeks and weeks to get to anything resembling American history, but I loved it. He not only was a master lecturer, but his knowledge and depth of learning were constantly on display. He casually dropped in names of historical sites we should see, books we should read; he somehow managed to work in lyrics from songs and he recited poetry as well. I wrote it all down in my notes and it often sent me scrambling in those pre-Google days to the library to track down the source of the poetry, the rest of the song, or the book he had mentioned. And he did it all without a single note. Here was a man who loved what he did, was good at it, and who put his passion and enthusiasm on display five days a week without fail for all of us to see. I had never seen anything like it, certainly not among my high school teachers, bless them. Quite simply, he set a model for how a professor should conduct his class that left me disappointed many times over in most of my other non-history classes that I took during the next 4 years. (It certainly wouldn’t have happened the next quarter with the professor who taught HIS 252, the second half of American history. He was deadly boring and shall remain nameless.) Carl Vipperman lit a fire in me that never burned out.

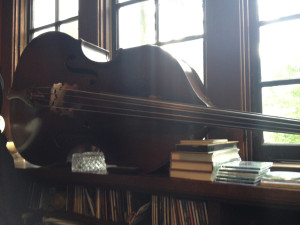

Carl almost pursued a musical career and maintained that love all his life. He played the upright bass in an Athens trio called “The Professors” for years.

I loved history but didn’t major in it, getting my undergraduate degree in journalism instead. But I immediately went back for a master’s degree in history and was privileged to be in the history department in LeConte Hall at a very special time. I took more classes with Carl and got to know his remarkable colleagues: Nash Boney, Phinizy Spalding, Jim Anderson, Emory Thomas, Jean Friedman, Ron Rader, Charlie Wynes, Joe Berrigan, Kirk Willis, Bill McFeely, Bob Pratt, Will Holmes, Bud Bartley, Lester Stephens, Alf Heggoy, John Inscoe, Tom Dyer, Aubrey Land. These were scholars who treated us with respect and expected us to do the same with each other. They welcomed us into their homes for social gatherings with a warmth of spirit and generosity, of collegiality, that set a very powerful example. I learned later it was a rare thing indeed in the academy. I have never forgotten it or them.

My path led me into public history, where I’ve had a wonderful and very fulfilling career that has allowed me to do things I never would have imagined when I began this journey on that long ago September Friday. In January 2006 I decided the time was way overdue for the man most responsible for launching me on that journey to know what he had done for me. So I wrote the following letter to Carl Vipperman:

‘Dear Dr. Vipperman: Please allow me to re-introduce myself to you. In my very first quarter at the University of Georgia, in the Fall of 1982, I took your American History class and it set me on the course of my life’s work as a historian and writer. For all these years, I’ve wanted you to know the enormous and positive influence you had on my life, but I’ve never taken the time to write you. Having gotten a doctorate and done a bit of teaching myself on the college level, I have had students approach me and tell me how much they enjoyed my class and appreciated how exciting I made my subject, how I had pushed them and challenged them to expand their minds. I would respond, ‘I studied under one of the masters.’ It always made me think about my own teachers–like you–and how much that was true of the best of them, but yet I’d never taken the opportunity to tell them so, to tell them how much they’ve shaped who I’ve become, the important role they played in my journey, and how much they mean to me–in short, to say a heartfelt and profound ‘thank you.’

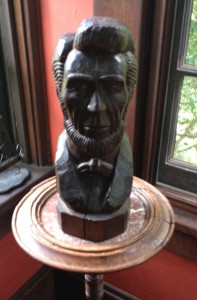

Carl was an accomplished woodworker, carving this bust of Abraham Lincoln.

First and foremost, you made history fun and exciting. Your teaching style was engaging and lively, your lectures were informative and humorous, yet packed with insight and analysis. And you did it all without any notes whatsoever! You could pick up on Monday morning exactly where you had left off on Friday, and never miss a beat. When the lecture was over, you always had time for students and their questions, and you never tired of conversations after class. Your warmth and generosity continue to inspire me, and the lessons you taught me in that classroom–as a scholar and as a gentleman–have stayed with me throughout my life. It was a privilege to be in your class.

As I watched you all those years ago, I asked myself, “How can I get a job doing what he’s doing?” I came to your office once and talked to you about a career in history, and though you discouraged me from getting an advanced degree in history due to the depressed job market, I didn’t listen! I went on to take your upper division course on Jefferson to the Civil War and though I received my undergraduate degree in journalism, I took my master’s degree in history there at UGA (working with Bill McFeely) and went on to get my Ph.D. in history at the University of Florida, where I studied under Bertram Wyatt-Brown. I would have never written my dissertation on South Carolina without your influence in that first class. It was you who first sparked my interest in South Carolina history, and it was your lectures that led me to take my first trip to Charleston. The vineyard of South Carolina history and historiography is a rich one, and your works on Rawlins and William Lowndes are both models of careful and thorough scholarship, good writing, and penetrating analysis. Indeed, anyone who labors in the field of history knows that their study would not be possible without the hard work and scholarship of those who have walked the vineyards before us and all who study the history of South Carolina stand in your debt.

They say that a teacher’s influence never ends, that their influence is passed down from generation to generation. You are living proof of that. Rest assured, my dear sir, you have touched many other lives besides mine. To quote Thomas Jefferson, writing to his friend John Adams in 1812, ‘No circumstances have lessened the interest I feel in these particulars respecting yourself; none have suspended for one moment my sincere esteem for you, and I now salute you with unchanged affection and respect. ‘ With all good wishes…’

They say that a teacher’s influence never ends, that their influence is passed down from generation to generation. You are living proof of that. Rest assured, my dear sir, you have touched many other lives besides mine. To quote Thomas Jefferson, writing to his friend John Adams in 1812, ‘No circumstances have lessened the interest I feel in these particulars respecting yourself; none have suspended for one moment my sincere esteem for you, and I now salute you with unchanged affection and respect. ‘ With all good wishes…’

Some time went by and I heard nothing. I thought, well, maybe my letter got thrown out with the junk mail. Who writes letters anymore anyway? Maybe I should have called or gone to visit instead. And then one day, nearly two months later, I found this email waiting for me one morning, with the subject line ‘Landmark Letter of January 31’:

‘Dear Dr. Deaton: I have delayed far longer than I intended in answering your letter and for that I must apologize. Part of the reason was the profound impact it made at our house. As I didn’t have my glasses, my wife Reggie opened the mail and started reading your letter to me. She was in tears before she got halfway through it, and when she finished, I said, ‘If I should fall over dead tomorrow, I want that letter read at my funeral, and I’d like for Stan Deaton to read it.’ If that comment sounds flippant, I assure you I could hardly be more serious. Your letter established a landmark in my professional life. Over the years I have received many compliments, mostly verbal and some written, and the year after I retired in 1994, the history department established the Graduate Teaching Assistant Award in my name, which I appreciate very much. But your letter is the first of its kind, coming from a student who did not major in history under my guidance, who wrote neither his thesis nor dissertation under my direction, who decided to become a historian against my market-prompted advice, who sought out the most challenging (and most rewarding) road to advanced degrees by choosing to study under McFeely and Wyatt-Brown, two of the best in the business

and among the most demanding in the profession, and who went on to establish himself as a respected member of my profession and especially among the community of historians in Georgia. What I found most gratifying and at the same time most humbling in your letter was that you considered the American history survey course you had with me to be a pivotal point in turning your attention toward history as a profession. That tends to vindicate what I have always believed, that introductory history courses are so important (1) for the enlightenment of ordinary American citizens on the historical character of their country and (2) for the recruitment of students like you for the history profession, that indifferent or uninterested instructors should never be allowed near them. Stan, in closing I must say that your letter was a great gift to the household of this old retired historian. You were lost to my memory before it came, but never again. Reggie and I thank you again for your priceless gift, and wish you every success and future happiness.’

Someone should read Carl’s letter at my funeral.

One month ago I spoke in Savannah at the memorial service for a dear friend of mine who committed suicide. One of his cousins said to me, ‘there are going to be some rough days ahead. Let’s all be there for each other.” I say the same to you today, in the spirit of my friend and mentor, who meant so much to me. Take the time to tell people what they mean to you, the influence they’ve played in your life. Before we are historians, scholars, teachers, we are human beings. Be kind to each other, lift each other up. Forgive other people, and be the first to reach out. Be there for each other. The academy—indeed, life in any profession—can be a petty, mean-s pirited, ugly business, with nasty backbiting and turf wars that can hurt feelings and leave friendships and reputations destroyed. Carl Vipperman was living proof that one can rise above all of that, and live one’s life with honor and integrity while treating others with kindness and respect. He told us in class one day that our lives would last longer than our careers, to fill it with things like community, culture, conversation and friends. Service to others. Absorption in things other than self is the secret to a happy life, well-rounded and well-lived, like Carl Vipperman’s. I regret that I didn’t go to greater lengths to see him and spend time with him in these latter years, but I’m grateful that at the end of the day he knew how much he meant to me and the influence he had on my life.

pirited, ugly business, with nasty backbiting and turf wars that can hurt feelings and leave friendships and reputations destroyed. Carl Vipperman was living proof that one can rise above all of that, and live one’s life with honor and integrity while treating others with kindness and respect. He told us in class one day that our lives would last longer than our careers, to fill it with things like community, culture, conversation and friends. Service to others. Absorption in things other than self is the secret to a happy life, well-rounded and well-lived, like Carl Vipperman’s. I regret that I didn’t go to greater lengths to see him and spend time with him in these latter years, but I’m grateful that at the end of the day he knew how much he meant to me and the influence he had on my life.

Peace to Carl and all who knew and loved him, and honor and glory to his memory.”