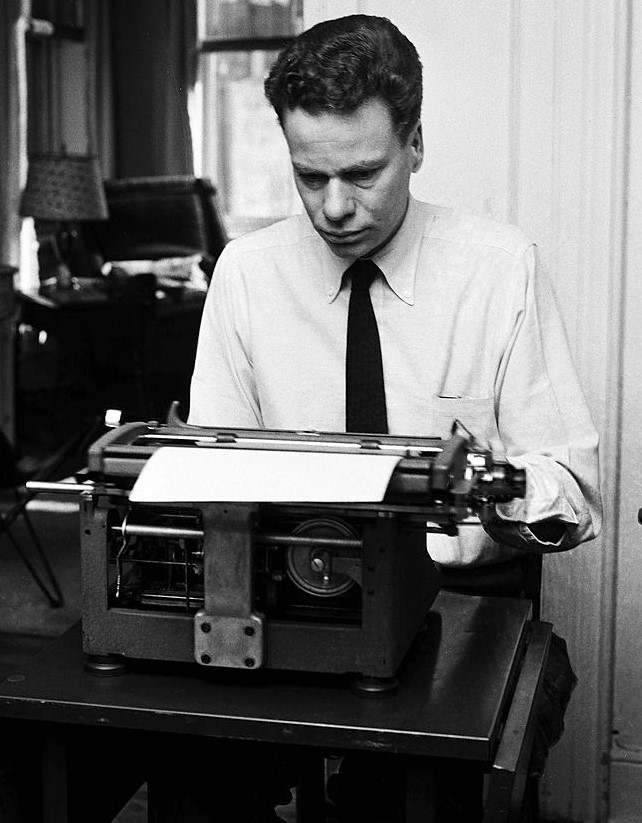

Charles Van Doren, who died April 9 at age 93, will forever be known as the man at the center of the quiz show scandals of the 1950s, the subject of the 1994 motion picture Quiz Show. Humiliated and ostracized when the truth emerged that Van Doren and other contestants of the brainy shows had been supplied the answers beforehand, Van Doren spent the rest of his life atoning for his betrayal of the public’s trust in a way that seems unimaginable now.

As Bret Stephens reminds us, the whole notion of “shame,” and in particular public shame, has radically changed over the course of the last 60 years. These days celebrities caught lying disappear from the public eye briefly and then reappear 6 months later for a teary “apology” interview and a lucrative tell-all memoir.

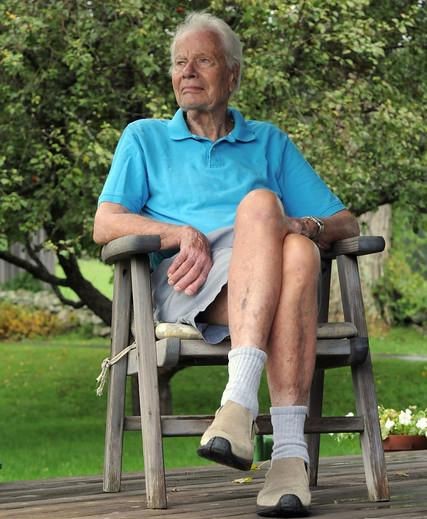

For Van Doren, his shame brought pariah-like status for the rest of his life, much of it self-imposed. Long after most of the world stopped caring about his sins, he still did. He declined to appear on camera talking about his mistakes, and 35 years after his appearance on “Twenty-One” he turned down an offer to be a consultant for the movie, refusing to profit from his lies. Who in the world would do that now? Not until 50 years after the scandal did he write about it.

Van Doren made amends in a more remarkable way, the only way that he knew how: by writing books about literature and the life of the mind. Before appearing on “Twenty-One,” Van Doren had been a literature professor at Columbia University, like his father Mark before him. After the scandal broke, his nascent academic career in ruins, Van Doren accepted an offer from family friend Mortimer Adler and went to work for Encyclopedia Britannica at its Chicago offices.

It was a gesture, one friend said, “that saved Charlie’s life.” Van Doren acknowledged it at Adler’s funeral in 2001: “There came the time when I fell down, face down in the mud, and he picked me up, brushed me off, and gave me a job.” Van Doren labored in relative obscurity for 20 years at Britannica, editing articles and contributing reviews to The Great Ideas Today, an annual companion volume to EB’s Great Books of the Western World.

In 1972, Van Doren co-wrote with Adler the completely revised and updated addition of Adler’s 1940 masterpiece, How to Read a Book: The Classic Guide to Intelligent Reading, which has never gone out of print. The book’s title has lent itself to jokes through the years, but as Clifton Fadiman pointed out, Van Doren and Adler don’t teach us “how to decipher words. That is merely a useful trick, just slightly above the capacity of a chimpanzee.” What this book teaches is how to read “books of some weight and density, into which went hard mental work and out which comes real mental change. Such reading involves a complex, often intense activity, not the passive reception of the author’s message. The result is not ‘finishing the book’ but starting something in the readers’ mind.”

A decade later Van Doren wrote in the 1983 edition of The Great Ideas Today a brilliant appreciation and review of Fernand Braudel’s pathbreaking The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II. It deserved a far wider audience than it received.

Charles Van Doren wrote many other books, and they are delightful to read. Pick up his 1991 volume, A History of Knowledge: Past, Present, and Future, which covers everything from Ancient Egypt to the Renaissance to AIDs and the computer revolution, and you’ll find many examples of gems like this one: “I have not met its author, but I have engaged Professor Berman in many silent conversations in the watches of the night.” Here is a sentiment every reader can share.

The Joy of Reading: A Passionate Guide to 189 of the World’s Best Authors and Their Works, first published in 1985 and revised in 2008, is even better. “Reading is my favorite thing to do,” he declares (that line was enough to hook me), and through a literary feast that doubles as a history of literature he proves it, writing knowledgeably and lovingly of books and authors from Homer to Harry Potter. It was Van Doren in this book who steered me toward Robert Fagles’ translations of Homer’s two great epics.

Unfortunately, Van Doren’s literary work received short shrift in the obituaries that appeared last week following his death, as I’m sure he always knew it would. He had no illusion about the fact that he would always be remembered for his part in one of the great shams of 20th-century popular culture.

But Charles Van Doren deserves more than to be remembered for his worst moment. His legacy is not to be found in the bad judgment of a 32-year-old who appeared on a long-forgotten TV show. Van Doren left something far more valuable: After falling face down in the mud, he spent his remaining 60+ years teaching and writing, hoping to inspire others to share his love of words, ideas, and books. His was the dignified example of a shamed man who made a very public mistake and thereafter lived a quiet life of redemption, a good and honorable and worthy life that should be remembered in its totality.

Van Doren wrote in his review of Braudel’s masterpiece, “It is a great historian who, when old, still is capable of making such an effort for the truth. And it is a great man who confesses the mistake that drove him to undertake it.”

It’s clear now that Charles Van Doren was writing about himself. May he rest in peace and his words–and example–live on.

Judicious and humane words, as always.

Nicely done. Thank you for helping us rememeber Charles Van Doren this way.