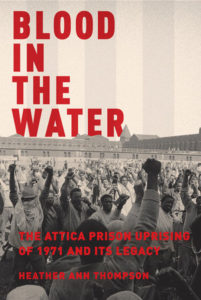

Heather Ann Thompson, Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy. Pantheon Books, 2016, 724 pp., $35.00.

At the Henry W. Grady School of Journalism at the University of Georgia, the late great Conrad Fink—Marine lieutenant, former Vietnam War correspondent, Associated Press veteran, and journalist par excellence—taught us that above all our mission was to “comfort the afflicted, and to afflict the comfortable,” to shine the light in dark places. Wherever things are done—for good or evil—by public institutions, he said, they are done in the name of the people of this republic, and therefore the people will always have a right to know what is done in their name.

At the Henry W. Grady School of Journalism at the University of Georgia, the late great Conrad Fink—Marine lieutenant, former Vietnam War correspondent, Associated Press veteran, and journalist par excellence—taught us that above all our mission was to “comfort the afflicted, and to afflict the comfortable,” to shine the light in dark places. Wherever things are done—for good or evil—by public institutions, he said, they are done in the name of the people of this republic, and therefore the people will always have a right to know what is done in their name.

In a similar vein, Voltaire long ago taught us that we should always rage against injustice, and that those in authority will forever bear watching because they will abuse that power. When they do, call them to account for it in the strongest terms possible. Theodore Besterman, the legendary Voltaire scholar, said of his subject’s life’s work, “Voltaire did not destroy injustice, but he took the first step, he put the unjust on the defensive.” Voltaire’s motto toward the end of his life? “Crush the infamous.”

In the finest sense of both of these charges, Heather Ann Thompson has fulfilled that mission and has shined a bright light on one of the darkest places imaginable and one of the most disturbing episodes in American history, the 1971 Attica prison uprising and its aftermath. She has put injustice on the defensive and in so doing has won the 2017 Pulitzer Prize for history.

First, a full disclosure: Heather Ann Thompson is my friend. I’ve known her and her husband Jon Wells for years, and they’re both great scholars and terrific people, so I can’t pretend to be impartial about this book. I think it’s great and would like it had it won nothing but the Irving Forbush Prize.

Jon Wells for years, and they’re both great scholars and terrific people, so I can’t pretend to be impartial about this book. I think it’s great and would like it had it won nothing but the Irving Forbush Prize.

But of course you don’t have to take my word for it. The 2017 Pulitzer judges awarded this book the prize for history for “a narrative history that sets high standards for scholarly judgment and tenacity of inquiry in seeking the truth about the 1971 Attica prison riots.”

Tenacity of inquiry is putting it mildly. The state of New York has had a vested interest for over 45 years in making sure the truth of what happened at Attica—during the takeover by the inmates, during the retaking by the state, and the fallout afterward—never sees the light of day.

Why would this be so? The state’s actions at Attica—taken in the name of the people—should have been able to bear the scrutiny of the most thorough investigation. As Thomas Jefferson said, “It is error alone which needs the support of government. Truth can stand on its own.”

But this has never been the case. From that day to this, the highest officials in the state of New York have done their best to make sure that the real story of this tragic episode never got out. It defies understanding how an entirely different generation of people, many of whom were not even born in 1971, could still be complicit in continuing to cover up the truth about Attica. And yet the documentary and artifactual evidence of what happened during the five days of September 9-13, 1971, and for years afterward, has been distorted, hidden away, or deliberately destroyed.

In a truly remarkable achievement of historical research and journalistic detective work, Heather relentlessly pursued the story of Attica using every weapon at her disposal to uncover the full story of the Attica uprising, the state’s brutal retaking of the prison that killed both hostages and inmates, and the barbaric retaliation meted out to prisoners in the days, months, and years afterwards. Martin Luther King, Jr. famously said that “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” In light of the Attica story, one wonders.

In the months leading up to September 1971, many of Attica’s prisoners petitioned and crusaded for better conditions at the prison, to no avail. On the morning of Thursday, September 9, in an uprising that was totally unplanned and unrehearsed, prisoners seized a chaotic moment in which a door was unexpectedly locked to rise up in protest against prison conditions and within hours nearly 1,300 inmates had taken control of Attica Correctional Facility. Seizing state and civilian hostages working at the prison (who naturally feared for their lives but who were protected by the inmates), prisoners negotiated with state authorities for basic civil and human rights that they felt they’d too long been denied. With tensions mounting and fears for the hostages safety, Governor Nelson Rockefeller sent the New York State Police and Attica’s Correctional Officers in with tear gas raining down and guns blazing.

Twenty-nine inmates and ten hostages were killed, all by state authorities, and over a hundred more were shot. In the bloody aftermath the state retaliated unmercifully for the uprising by torturing prisoners with sadistic acts and denying them adequate medical care. The officials also lied to hostage families about who killed their loved ones, and to the American public about what really happened. From Governor Rockefeller on down, the state went to extraordinary lengths to cover up official actions, protect state police from criminal charges, all while denying any official culpability for mental and physical damage inflicted on hostage and inmate survivors and their families that continues to this day.

It’s a shameful story that Heather has dragged kicking and screaming into the light of day through Freedom of Information requests, interviews with survivors, over a decade of dogged research in archives across the country, and sheer determination to not let this story remain hidden from the public any longer. In addition to the adulation and prizes, she’s also received threats and been vilified.

As you would expect from a prize winner, this book is a compelling, page-turning read, but make no mistake: some of the graphic descriptions of what happened at Attica will—and should—turn your stomach.

The author’s attention to the smallest details is impressive. Just two examples among hundreds: on the morning the uprising began, Heather describes a moment when the inmates battered down a gate that didn’t just give way; one of the bars securing the gate to the cement “broke in half about fifteen inches down from the ceiling” (p. 54), a small nugget gleaned from a close reading of a very long after-action report. Similarly, after the retaking, inmates struggled to get word out to loved ones that they were alive, if not safe from state retribution and retaliation. They smuggled a red spiral-bound notebook from cell to cell, into which inmates wrote notes to family members in hopes it would get over the walls. State police confiscated it, and 40 years later Heather held it in her hands in a warehouse of the New York State Museum, its messages finally seeing the light of day. The notebook and the rest of the documents and artifacts she saw in that warehouse have subsequently disappeared.

After years of litigation, the state of New York finally settled with a group of former Attica prisoners in 2000, and with surviving hostages and their families in 2005. To date there have been no official apologies or admissions of wrong-doing, and no trooper or correctional officer was ever charged with a crime for their actions during the re-taking.

Blood in the Water isn’t just about what happened in 1971, of course. As we continue to live in the era of mass incarceration, the populations of this country’s ever-expanding prisons receive the least sympathy/empathy/understanding of all our fellow human beings. It’s customary for us to turn away from what happens behind those walls, secure in the knowledge that “whatever they get, they deserve. They should have thought about that before they raped, murdered, shot, stole, or…..” whatever else “they” did. When prison rebellions occur, our collective response isn’t to try to understand why, it’s to crack down even harder on the system and those in it.

What civil or human rights, after all, do convicted criminals have? That question always reminds me of the exchange between William Roper and Sir Thomas More in A Man For All Seasons, when Roper says he would cut down every law in England to get to the Devil. More replied, “And when the last law was down, and the Devil turned ’round on you, where would you hide, the laws all being flat? Yes, I’d give the Devil benefit of law, for my own safety’s sake!”

As Attica and its aftermath make clear, in a nation that holds any moral claims to standing for basic human rights, we turn a blind eye to what is done in our name—in prisons or anywhere else—at our own peril. This book is a reminder to we who need reminding that indifference to injustice and human suffering is obscene and immoral, no matter the source, and that in a self-governing republic power must always be held accountable.

As Voltaire said, “Every man is guilty of the good he did not do.”