Missing: One major league baseball team. Answers to the name of Atlanta Braves. Last seen April 28 after win over Cleveland. Went missing on plane flight to Seattle, not seen since. Began the 2024 season red hot, winning 19 out of 26 games. Formerly known to score runs in great bunches, particularly in the early innings. Also previously hit massive home runs, at record pace last season. Has not been seen at former home on Comcast since May 1. Last observed desperately clutching World Series rings. Team led away by balding friendly White man in his 60s with street name “Snit.” Other team members may respond affirmatively to names “Money Mike” and “The Big Bear.” The latter is the only player likely to be on base and might be wearing oven mitts. Fans are frantic to locate Braves while season still salvageable. Approach with caution—team can swing hard but usually misses. If you have any information, please call 911, Major League Baseball, and Truist Park immediately.

Missing: One major league baseball team. Answers to the name of Atlanta Braves. Last seen April 28 after win over Cleveland. Went missing on plane flight to Seattle, not seen since. Began the 2024 season red hot, winning 19 out of 26 games. Formerly known to score runs in great bunches, particularly in the early innings. Also previously hit massive home runs, at record pace last season. Has not been seen at former home on Comcast since May 1. Last observed desperately clutching World Series rings. Team led away by balding friendly White man in his 60s with street name “Snit.” Other team members may respond affirmatively to names “Money Mike” and “The Big Bear.” The latter is the only player likely to be on base and might be wearing oven mitts. Fans are frantic to locate Braves while season still salvageable. Approach with caution—team can swing hard but usually misses. If you have any information, please call 911, Major League Baseball, and Truist Park immediately.

Category Archives: Writings

Boswell and Johnson Walk Into a Bookstore: May 16, 1763

On Monday, May 16, 1763, 261 years ago this week, young James Boswell was introduced to Samuel Johnson at Thomas Davies’s bookshop on Russell Street, near Covent Garden in London. Boswell was a 22-year-old Scotsman, perhaps best described as what we’d today call a “social influencer”—he wanted to be famous, and he was hugely ambitious. Johnson was 53, an already-acclaimed writer and author that Boswell desperately wanted to meet. Boswell famously described their meeting years later: Boswell went to his friend Davies’s bookstore for afternoon tea, and in walked Johnson. Introducing the two, and knowing the grumpy Johnson’s dislike of the Scots, Davies playfully revealed Boswell’s nationality. Boswell blurted out, ““Mr. Johnson, I do indeed come from Scotland, but I cannot help it.” Johnson’s riposte: “That, Sir, I find, is what a very great many of your countrymen cannot help.” Such was the beginning of one of the most famous—if bumpy—friendships in all of literature.

On Monday, May 16, 1763, 261 years ago this week, young James Boswell was introduced to Samuel Johnson at Thomas Davies’s bookshop on Russell Street, near Covent Garden in London. Boswell was a 22-year-old Scotsman, perhaps best described as what we’d today call a “social influencer”—he wanted to be famous, and he was hugely ambitious. Johnson was 53, an already-acclaimed writer and author that Boswell desperately wanted to meet. Boswell famously described their meeting years later: Boswell went to his friend Davies’s bookstore for afternoon tea, and in walked Johnson. Introducing the two, and knowing the grumpy Johnson’s dislike of the Scots, Davies playfully revealed Boswell’s nationality. Boswell blurted out, ““Mr. Johnson, I do indeed come from Scotland, but I cannot help it.” Johnson’s riposte: “That, Sir, I find, is what a very great many of your countrymen cannot help.” Such was the beginning of one of the most famous—if bumpy—friendships in all of literature.

I wrote about Boswell in another blog entry from December 10, 2014, nearly 10 years ago, and on this auspicious anniversary of that famous meeting, I can do no better than to quote a bit from that post (with slight editing) again here:

“I am lost without my Boswell.” So says Sherlock Holmes about Dr. Watson in “A Scandal in Bohemia.” Boswell is most famous as the author of the monumental biography, The Life of Samuel Johnson, first published in 1791 and never out of print. I bought a nice Easton Press edition in three volumes a few years back and loved it. Boswell is best known as Johnson’s biographer, but he was a fascinating and complex man in his own right, well worthy of our attention, and his published journals are just the place to start.

Boswell would be well at home in today’s world of social media. He kept extensive journals throughout his life, covering the most intimate details of his private goings-on and detailed transcriptions of his conversations with the great men and women of 18th-century Britain, including Georgia’s founder James Edward Oglethorpe, Samuel Johnson of course, the artist Joshua Reynolds, actor David Garrick, writer Oliver Goldsmith, the aforementioned David Hume, Voltaire, and many, many others.

And just like today’s most avaricious social media posters, he held nothing back, even when he probably should have. He wrote about everything: politics, art, literature, court intrigues, his sexual and sensual escapades (including cavorting with London’s prostitutes and contracting and living with an STD), the peccadilloes of his friends and associates, falling out with his father over his chosen career, his fear of ghosts, and everything else you can imagine. He was an inveterate sinner who feared damnation but would walk out of a church and have sex with a prostitute. Sometimes he would miss the sermon because he was lusting over a woman in another pew. It is about as revealing a snapshot of everyday life in 18th-century Britain—and a man driven by and forever at war with his passions—as we are ever likely to have, and it is all fascinating, a ripping good read.

Boswell died in 1795 at age 54, leaving behind a wealth of personal papers and journals that he hoped would one day be published. His family, however, had other ideas. Generations of his descendants thought his writings inappropriate and scandalous, detailing as they did his every whim, fancy, and indiscretion. They were also ashamed of their association with a man whom they considered to have lowered himself by acting the sycophant to the overbearing and boorish Johnson simply to obtain material for his biography.

Boswell’s descendants didn’t exactly lose his writings, but it’s safe to say they put them away and mostly forgot about them as they passed from generation to generation. They were “rediscovered” in the 1920s and 1930s in a croquet box at Malahide Castle in Ireland and in a stable loft at the home of a Scottish laird at Fettercairn House near Aberdeen.

The story of the Boswell Papers’ disappearance and re-discovery is told in fascinating if sometimes excruciating details in Frederick Pottle’s Pride and Negligence: The History of the Boswell Papers (1981) and in David Buchanan’s more enthralling The Treasures of Auchinleck: The Story of the Boswell Papers (1974). Pottle was a lifelong Boswell scholar and edited, in the “Boswell Factory” at Yale, all but one of the thirteen volumes of the popularly published journals that begin with the London Journal.

When Boswell’s London Journal, 1762-1763, was first published in 1950, it was a surprising best seller and one can see why. It’s racy and titillating, gossipy and erudite, introspective and philosophical, witty and just plain fun. There are two famous scenes in these pages: Bozzy’s first meeting with Johnson on May 19, 1763, of course, but also the memorable day when he confronts his girlfriend Louisa as to whether she knowingly gave him a venereal disease: “Madam, I have had no connection with any woman but you these two months. I was with my surgeon this morning, who declared I had got a strong infection, and that she from whom I had it could not be ignorant of it. Madam, such a thing in this case is worse than from a woman of the town, as from her you may expect it. You have used me very ill. I did not deserve it.” Louisa protested her innocence, but to no avail. Boswell stormed out and ended the relationship. Later in a quieter moment he confessed to his journal that he’d had this same disease twice before, but if he ever apologized to poor Louisa, the journal is silent.

Boswell kept on writing till his last days, and though his father scolded him for keeping “a register of his follies and communicat[ing] it to others as if proud of them,” we are the ultimate beneficiaries. There are twelve other volumes after this one and I look forward to reading them all.

***

With the publication of Boswell’s Journals, the perception of the famous friendship has begun to change: Boswell has come into his own as one of the great historical figures of the 18th century, a flawed genius that, for many people, now eclipses Johnson’s brilliance. In Clifton Fadiman’s words, “the disciple is beginning to overshadow the master.” Boswell, he rightly insisted, “is more than a superb reporter. He is an artist, just as surely as Rembrandt.”

The literature on Boswell, Johnson, and their famous friendship is vast, but start, as mentioned above, with the London Journal, then read as many of the other Journals as you desire. I’ve since read six volumes now, with seven more to go. They never disappoint. And of course, read Boswell’s Life of Johnson, which critic Michael Dirda called “the greatest of all biographies and probably the most entertaining book in English literature.”

But you don’t have to stop there. In addition to the Pottle and Buchanan books cited above, I recommend the following: Frederick Pottle, James Boswell: The Earlier Years, 1740-1769 (1966); W. Jackson Bate, Samuel Johnson (1977, winner of the 1978 Pulitzer Prize for Biography); Frank Brady, James Boswell: The Later Years, 1769-1795 (1984); Peter Martin, A Life of James Boswell (2000); Liza Picard, Dr. Johnson’s London (2001); Adam Sisman, Boswell’s Presumptuous Task: The Making of the Life of Dr. Johnson (2001) Peter Martin, Samuel Johnson: A Biography (2008); John B. Radner, Johnson and Boswell: A Biography of Friendship (2013); and Leo Damrosch, The Club: Johnson, Boswell, and the Friends Who Shaped An Age (2020).

But you don’t have to stop there. In addition to the Pottle and Buchanan books cited above, I recommend the following: Frederick Pottle, James Boswell: The Earlier Years, 1740-1769 (1966); W. Jackson Bate, Samuel Johnson (1977, winner of the 1978 Pulitzer Prize for Biography); Frank Brady, James Boswell: The Later Years, 1769-1795 (1984); Peter Martin, A Life of James Boswell (2000); Liza Picard, Dr. Johnson’s London (2001); Adam Sisman, Boswell’s Presumptuous Task: The Making of the Life of Dr. Johnson (2001) Peter Martin, Samuel Johnson: A Biography (2008); John B. Radner, Johnson and Boswell: A Biography of Friendship (2013); and Leo Damrosch, The Club: Johnson, Boswell, and the Friends Who Shaped An Age (2020).

As for the date of that famous meeting, Boswell missed dying on the anniversary itself by three days—32 years later—on May 19, 1795. He is buried in the family vault at Auchinleck Old Churchyard in Auchinleck, Scotland. Johnson died on December 13, 1784, at age 75, and is buried in Westminster Abbey.

But how’s this for coincidence? Frederick Pottle, the man who spent nearly his entire professional career as the editor and biographer of Boswell and his papers, considered the greatest Boswell scholar of all, himself died on the anniversary of that famous meeting, on May 16, 1987, at age 89. I suspect that would have pleased Dr. Pottle very much. No Westminster Abbey for him: Pottle is buried, appropriately, at Elmwood Cemetery in quiet Otisfield, Maine.

Alas, the Boswell Papers Project at Yale that Pottle captained for so long is no more, unceremoniously shut down by Yale bean counters during the pandemic. But the great friendship that began on that long-ago Monday in a London bookstore lives on for all of us to discover and explore, not only through print but now also on numerous social media pages and forums, dedicated to every aspect of Boswell, his life, and his world, in all his wickedness and glory—which he most assuredly would have loved.

Savannah, May 16, 2024

The Freshest Advices, May 10, 2024

Hello again. It’s been 8 months since I’ve written in this space (not counting two editorials), so it’s good to be back in between podcasts and other duties as assigned. Let’s dive right in, shall we?

Hello again. It’s been 8 months since I’ve written in this space (not counting two editorials), so it’s good to be back in between podcasts and other duties as assigned. Let’s dive right in, shall we?

Baseball, and Trying to Watch Baseball: The Beloved Braves got off to a hot start, despite losing Spencer Strider for the year, but at this moment they’ve cooled off considerably and let the Hated Phillies (HPs) catch and pass them in the standings. We’re now looking up at the HPs from second place. I doubt that will hold for the season, but if it does, I’m fine with that. Maybe we can reverse the trend from the last two years and go into the postseason as a Wild Card team, make the HPs sit around for a week as their reward for winning the division, and then beat them in the best-of-five second round. Between now and then, we will pray to Hermes, the Greek god of coaxial cable, that Comcast and Bally Sports can work out their problems so that long-suffering fans can actually watch the team again. More than any other league, Major League Baseball makes it incredibly difficult to actually watch the sport. From regional sports networks like Bally that are forever fighting with carriers Comcast and DirecTV, to Friday games on Apple TV, Saturday games on Fox or FS1, Sunday games on ESPN, and whatever games aren’t blacked-out in your region on the expensive MLB app, baseball can be harder to find than Uncle Pootsie’s dentures. Of course, if the Braves continue to play like they did in Los Angeles last weekend, we’ll pay Comcast to keep them off the air and set fire to our remotes in protest. Stay tuned.

Books, Books, and Books: If you’ve been listening to the recent Off the Deaton Path podcasts—and of course you have—then you know I’ve read some great books this year: Michael Thurmond’s new take on Georgia founder James Oglethorpe, Jerry Grillo’s biography of Johnny Mize, the Big Cat, David Henkin’s fascinating exploration of the origins of The Week, Pulitzer-Prize winner David Blight’s uncovering the unexpected history of Yale and Slavery, John O’Connor’s Secret History of Bigfoot, Clayton Trutor’s award-winning Loserville, and Elizabeth Varon’s pathbreaking biography of Confederate general James Longstreet.

What else have I been reading in 2024? The history of the British monarchy fascinates me—as does the death of famous people—and Dr. Suzie Edge has become a Tik-Tok star because of her incredible knowledge on the history of the Royals and all the horrible ways they’ve died. Check out her recent Mortal Monarchs: 1,000 Years of Royal Deaths.

What else have I been reading in 2024? The history of the British monarchy fascinates me—as does the death of famous people—and Dr. Suzie Edge has become a Tik-Tok star because of her incredible knowledge on the history of the Royals and all the horrible ways they’ve died. Check out her recent Mortal Monarchs: 1,000 Years of Royal Deaths.

Staying with the theme, if, like me, you’ve always wanted to get a peek behind the curtain at your local funeral home—or even if you haven’t—I highly recommend Caitlin Doughty’s Smoke Gets in Your Eyes and Other Lessons From the Crematory. Yes, it’s every bit as gruesome as you’d think but endlessly fascinating.

Speaking of gruesome, who knew that Joseph Stalin, in addition to being one of the most vicious tyrants in world history, was also a voracious reader? And he wrote in his books, many of which have survived and are preserved in Moscow. It’s all detailed in Geoffrey Roberts’s Stalin’s Library: A Dictator and His Books.

Speaking of Stalin, I also read The Groves of Academe, Mary McCarthy’s 1952 Joseph McCarthy-era campus novel that a recent New York Times article proclaimed as the novel that explains the current crisis in American higher education. To quote from the NYT: “Every squawking buzzard in American public life — every quarrel about race, class, sex, foreign policy, pronoun usage — takes wing from or comes home to roost on campus. The crisis is permanent, structural, a feature of the conflicting expectations we impose on our schools. There is a vast body of scholarship to explain why this is so. Academia is a serious place, and it takes itself seriously. But it is also, like Hollywood or Washington, profoundly ridiculous — the kind of symbolically overburdened, sociologically peculiar environment that can only really be understood through satire. Luckily, we have an entire literary subgenre, the campus novel, to fulfill that requirement.”

McCarthy’s book is one very notable contribution to that subgenre and it captures the anti-Communist frenzy of the early 50s quite well. My favorite campus novel remains 1954’s Lucky Jim by Kinglsey Amis.

A strong runner-up, however, also read recently, has to be Julie Schumacher’s hilariously funny Dear Committee Trilogy: Dear Committee Members, The Shakespeare Requirement, and The English Experience. The trilogy follows the travails of Jason Fitger, a sad sack, rumpled aging professor and chair of creative writing and literature at Payne University, “a small and not very distinguished liberal arts college in the Midwest.” For all that our college campuses are ground zero for the country’s culture wars, Schumacher’s trio of books will give you a cringe-worthy too-real-for-comfort look at the smallness and silliness of cut-throat university politics and the personalities that engage in them.

A strong runner-up, however, also read recently, has to be Julie Schumacher’s hilariously funny Dear Committee Trilogy: Dear Committee Members, The Shakespeare Requirement, and The English Experience. The trilogy follows the travails of Jason Fitger, a sad sack, rumpled aging professor and chair of creative writing and literature at Payne University, “a small and not very distinguished liberal arts college in the Midwest.” For all that our college campuses are ground zero for the country’s culture wars, Schumacher’s trio of books will give you a cringe-worthy too-real-for-comfort look at the smallness and silliness of cut-throat university politics and the personalities that engage in them.

Speaking of campus politics in popular culture, check out Lucky Hank, an 8-part TV series that aired on AMC last spring and again this winter. It starred Bob Odenkirk (Breaking Bad, Better Caul Saul) as Hank Devereaux, the English department chair at a small Pennsylvania college, based on Richard Russo’s 1997 novel, Straight Man. The casting was spot-on (watch for Tom Bower, who played Mary Ellen Walton’s husband Kirk on The Waltons 45 years ago, as Hank Devereux Sr.) and the acting brilliant, perfectly capturing the personalities at play in the modern academy. I haven’t read Russo’s book, so I’ve no idea how faithful the show was to it, but we’ll save the subject of turning books into other mediums—or using another author’s book as the basis for your own—for another blog post.

Okay, maybe just a little bit about books adapted into movies. I recently re-read Richard Adams’s Watership Down, first published in 1972 and then turned into a 1978 animated film, a 1999-2001 TV series, and a 2018 animated re-boot. I haven’t watched any of them and probably won’t, because I love the book too much as a book to have it filtered through another lens. I first read this novel in Ms. Hewitt’s 11th-grade literature class at South Gwinnett High School in 1981 (God bless you, Ms. Hewitt, wherever you are), and re-read it two years later after my first year at UGA. The novel had a huge impact on me at that time, and I’ve hesitated to re-read it as a full-blown adult for fear I would find the whole story disappointing and not what I remembered. Turns out, the opposite is true—the book spoke to me much more now, 40+ years later, than it did then, sometimes in profoundly moving ways. This is the power of re-reading: the book hasn’t changed, but you have, and what you bring to it has altered, matured (hopefully), and deepened with the passage of time. In all likelihood, I’ll read it again in 10 years, if not before.

Okay, maybe just a little bit about books adapted into movies. I recently re-read Richard Adams’s Watership Down, first published in 1972 and then turned into a 1978 animated film, a 1999-2001 TV series, and a 2018 animated re-boot. I haven’t watched any of them and probably won’t, because I love the book too much as a book to have it filtered through another lens. I first read this novel in Ms. Hewitt’s 11th-grade literature class at South Gwinnett High School in 1981 (God bless you, Ms. Hewitt, wherever you are), and re-read it two years later after my first year at UGA. The novel had a huge impact on me at that time, and I’ve hesitated to re-read it as a full-blown adult for fear I would find the whole story disappointing and not what I remembered. Turns out, the opposite is true—the book spoke to me much more now, 40+ years later, than it did then, sometimes in profoundly moving ways. This is the power of re-reading: the book hasn’t changed, but you have, and what you bring to it has altered, matured (hopefully), and deepened with the passage of time. In all likelihood, I’ll read it again in 10 years, if not before.

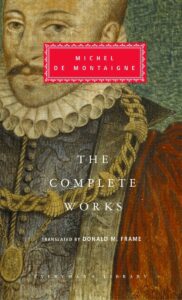

Great Books: Just recently I finished reading Montaigne’s Essays. Michel de Montaigne was the famous 16th-century Frenchman who practically invented the literary form we know today as the essay. Writing in his famous tower almost 450 years ago, Montaigne wrote mainly about himself—his mantra being “What do I know?”—and in so doing he wrote about all of us as well. Sarah Bakewell, in her award-winning 2012 book, How to Live, or A Life of Montaigne In One Question and Twenty Attempts at an Answer described it this way: “The twenty-first century is full of people who are full of themselves. . . thousands of individuals fascinated by their own personalities and shouting for attention. They go on about themselves; they diarize and chat, and upload photographs of everything they do. Uninhibitedly extrovert, they also look inward as never before. Even as bloggers and networkers delve into their private experience, they communicate with their fellow humans in a shared festival of the self. . .By describing what makes them different from anyone else, the contributors reveal what they share with everyone else: the experience of being human. This idea—writing about oneself to create a mirror in which other people recognize their own humanity—has not existed forever. It had to be invented….it can be traced to one person: Michel de Montaigne.”

Great Books: Just recently I finished reading Montaigne’s Essays. Michel de Montaigne was the famous 16th-century Frenchman who practically invented the literary form we know today as the essay. Writing in his famous tower almost 450 years ago, Montaigne wrote mainly about himself—his mantra being “What do I know?”—and in so doing he wrote about all of us as well. Sarah Bakewell, in her award-winning 2012 book, How to Live, or A Life of Montaigne In One Question and Twenty Attempts at an Answer described it this way: “The twenty-first century is full of people who are full of themselves. . . thousands of individuals fascinated by their own personalities and shouting for attention. They go on about themselves; they diarize and chat, and upload photographs of everything they do. Uninhibitedly extrovert, they also look inward as never before. Even as bloggers and networkers delve into their private experience, they communicate with their fellow humans in a shared festival of the self. . .By describing what makes them different from anyone else, the contributors reveal what they share with everyone else: the experience of being human. This idea—writing about oneself to create a mirror in which other people recognize their own humanity—has not existed forever. It had to be invented….it can be traced to one person: Michel de Montaigne.”

The essays are at once easy and difficult to describe. Montaigne set about examining his interior life in 107 essays that have titles like “Of Friendship,” “Of Liars,” “Of the power of the imagination,” “Of drunkenness,” “Of books.” As Clifton Fadiman described them in The Lifetime Reading Plan, “They are formless, they rarely stick to the announced subject.” In fact, Montaigne may start off writing about the subject in the title of the essay, and then for the next dozen pages he may write about body odors, strange people who turn up at his house, the way his servants talk, or how he can’t eat certain foods. One essay that is ostensibly about the Roman poet Virgil discusses the size of Montaigne’s sexual organs and the pros and cons of marriage. They are literally all over the map, and loaded with quotations from his other reading, usually the ancient Greeks and Romans. Fadiman again: “Montaigne is not only the first informal essayist but incomparably the best. He writes as if he were continually enjoying himself, his weaknesses and oddities and stupidities no less than his virtues.”

All of which is why he’s read as avidly today as he was in his own time. The Essays went through multiple editions in French in Montaigne’s own lifetime and were first translated into English by John Florio in 1603. Readers have included Francis Bacon, William Shakespeare, Lord Byron, William Makepeace Thackeray, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Virginia Woolf, T.S. Eliot, and Aldous Huxley. Quoting the Encyclopedia Britannica: “Voltaire and Denis Diderot saw in him a precursor of the free thought of the Enlightenment. Jean-Jacques Rousseau rightly considered Montaigne the master and the model of the self-portrait. Flaubert kept the Essays on his bedside table and recognized in Montaigne an alter ego.” Many others still do right up to the present day.

Here are some of his bon mots:

“I used to mark the burdensome and gloomy days as extraordinary. Those are now my ordinary ones; the extraordinary are the fine serene ones.”

“It is a rare life that remains well ordered even in private.”

“I set little value on my opinions, but I set just as little on those of others.”

“Old age puts more wrinkles in our minds than on our faces.”

“I am all in the open and in full view, born for company and friendship.”

“It is impossible to discuss things in good faith with a fool.”

“If you do not know how to die, don’t worry. Nature will tell you what to do on the spot, fully and adequately. She will do this job perfectly for you, don’t bother your head about it.”

“If your doctor does not think it good for you to sleep, to drink wine, or to eat such-and-such a food, don’t worry; I’ll find you another who will not agree with him.”

“On the loftiest throne in the world we are still sitting on our own rump.”

I suggest Donald Frame’s translation, first published in 1958. The Essays are broken up into three “Books” that run to well over 800 pages. You need not read them from start to finish; as Fadiman noted, “you may wander about almost at will in Montaigne. He should be read as he wrote, unsystematically.” Alas, I’m too structured for that—I read one Book each year over the last three years, consuming the elephant in small bites.

However you decide to read him, I highly recommend making Montaigne and his Essays a part of your life, slowly, over a number of months or years. Consume him at your leisure, the way Fadiman suggests. You’ll discover, as so many others have over the last 400+ years, a kindred spirit who “appeals to that part of us more fascinated by the questions than the answers.”

Pulitzer Prizes: Finally, the 2024 Pulitzer Prizes were announced this week, and hurrahs are due to Director Lisa Bayer and the University of Georgia Press, publishers of this year’s winner for poetry, Tripas: Poems, by Brandon Som. Anytime a university press publishes a Pulitzer winner it’s a big deal, and when the winners are published by our good friends at UGA Press, it’s even better. Congratulations, one and all.

Stay safe, and until next time, thank you for reading.

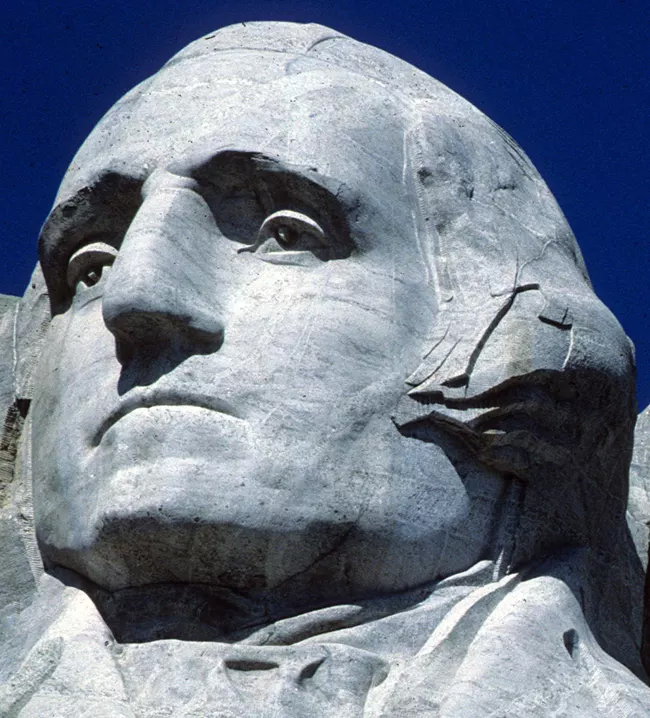

George Washington and The Road Not Taken

This first appeared as an editorial in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution on Monday, February 19, 2024.

Percy Shelley wrote that power poisons every hand that touches it. History is littered with the names of those who attained power ruthlessly, wielded it arbitrarily, and refused to give it up.

Percy Shelley wrote that power poisons every hand that touches it. History is littered with the names of those who attained power ruthlessly, wielded it arbitrarily, and refused to give it up.

In one of history’s most famous stories, King George III asked the American painter Benjamin West what George Washington would do after winning independence. West replied, “They say he will return to his farm.” King George was incredulous: “If he does that, he will be the greatest man in the world.”

At the end of the American Revolution, George Washington rode to Annapolis, Maryland, where Congress was in session, to resign the commission he had accepted in June 1775, eight years earlier.

Consider what he was doing. Congress had vested full military authority in Washington to lead the Continental Army as commander in chief, and he had done so for the duration of the conflict. At least twice toward the end of that period, however, he was encouraged by others to seize power as dictator.

The Confederation Congress was weak and had virtually no ability to raise revenue to pay its expenses, chief among them the back pay of soldiers and officers of the Continental Army, months in arrears. Now was the time for Washington to strike.

On May 22, 1782, Washington received a letter from Colonel Lewis Nicola of Pennsylvania, proposing that Washington seize power with the help of the army and declare himself dictator or king. It had apparently been talked about for some time. Nicola was proposing nothing less than a military coup.

Revolutions often dissolve into dictatorships. Chaos breeds the conditions for a strong man to seize power, claiming to have all the answers and authority to solve complex problems. For many people this was where the road of self-government always ended. Why should the American Revolution have been any different?

If there was ever a moment in American history when one individual could have felt justified in seizing power and doing the unthinkable, that was it. There was no central government, no executive branch, no federal bureaucracy, no Supreme Court, and he was head of the national army. Washington could not be charged with acting unconstitutionally because there was no Constitution. Rule of law? Washington could have been the law.

No. Washington responded to Nicola with scorn and contempt. “Be assured, Sir, no occurrence in the course of the war has given me more painful sensations than such ideas existing in the Army as you have expressed, and I view them with abhorrence and reprehend with severity. I am at a loss to conceive what part of my conduct could have given encouragement to an address which to me seems big with the greatest mischiefs that can befall my country. You could not have found a person to whom your schemes were more disagreeable.”

Consider the reception Nicola’s letter might have received in other hands than Washington’s: “If you have any regard for your country, for posterity, or respect for me, banish these thoughts from your mind, and never communicate a sentiment of like nature.”

It happened again a year later. In March 1783, Washington refused to support the so-called “Newburgh Conspiracy,” a thinly veiled attempt by Continental officers to extort back pay from Congress by threatening a military coup.

Only one American could play the role of Caesar, and he twice refused to do it.

Two days before Christmas in 1783, Washington stood before Congress, the hall crowded with spectators, his hands visibly trembling. He spoke in a faltering voice. “Mr. President, having now finished the work assigned to me, I retire from the great theatre of Action; and bidding an Affectionate farewell to this August body under whose orders I have so long acted, I here offer my Commission, and take my leave of all the employments of public life.” He walked out, the hall ringing with applause.

Thomas Jefferson, present that day, understood the enormity of what he had witnessed: “The moderation and character of a single man has probably prevented the revolution from being closed, as most others have been, by a subversion of the liberty it was intended to establish.”

Had Washington possessed greater ambition and less character, the history of the United States would have been far different over the last two centuries.

After serving two terms as President, Washington walked away voluntarily again.

By surrendering power and refusing a dictatorship, Washington launched the American experiment on a firm foundation of principled and moral leadership that established that anyone who deviates from this model would be turning their back on one of the core values of the American republic—that ours is a government of laws, not of men—and one of the bedrock principles of American political leadership.

He secured to all mankind the gift of the world’s most enduring self-governing republic that, with all its flaws, remains an inspiration to the world.

The experiment continues, the outcome still in doubt. As Lincoln said, no one will ever conquer us—as a nation of free men and women, we shall live forever or die by suicide.

That need not be our destiny. When in doubt, look to our lodestar. As was said of Voltaire, so we can say about Washington: Consider that life and take courage.

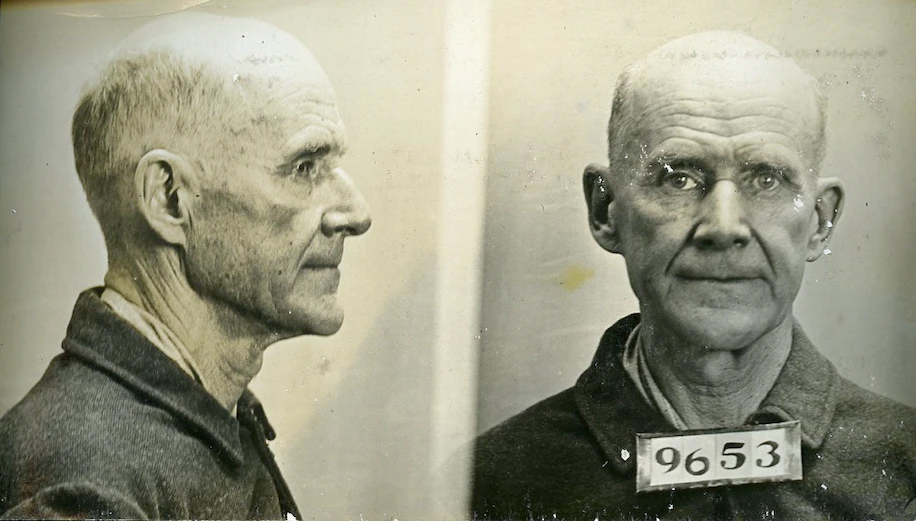

Prisoner #9653 For President

A shorter version of this essay first appeared in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution on Wednesday, January 3, 2024, and can be seen here.

Many people are asking, can a candidate run for the presidency from prison? Yes, and it’s happened before—to a Socialist who received nearly a million votes.

Eugene Debs ran as the Socialist Party nominee for president five times in the six presidential elections between 1900 and 1920—and in 1920 he ran from the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary.

Debs was born in Terre Haute, Indiana, in 1855. He left home at age fourteen to work on the railroad and became involved in the nascent efforts to organize labor unions. Before his 20th birthday he helped create a local lodge of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen, rising to become a national officer within five years. By the time he was 30 he was serving in the Indiana legislature.

Debs was a labor organizer, but he was not anarchist. He had been shocked by Chicago’s Haymarket Riots of 1886. Though he was the son of Alsatian immigrants, he still indulged in nativist rhetoric, insisting that the incoming tide of Eastern European Jews and Southern European Catholics in the late 19th century threatened Protestant White Americans. “The Dago,” he said, “works for small pay and lives far more like a savage or a wild beast than the Chinese.” Like a modern-day cable news talking head, he warned that “Italy has millions to spare, and they are coming.” He denounced the influx of Russian Jews as “criminals and paupers.”

By the 1890s, the growing power of corporations and the threat they posed to workers led Debs to oppose all attempts to divide workers against themselves based on ethnicity. Class, not religion, was his fault line. He led the American Railway Union in a successful strike for higher wages against the Great Northern Railway in April 1894.

Debs gained greater renown—and vilification—in 1895 when he was sentenced to six months in jail for his role in leading the Chicago Pullman Palace Car Company strike, which severely disrupted rail traffic in the Midwest during the summer of 1894. That strike was historic: it marked the first time that the Federal government resorted to an injunction to break the strike.

Sitting in jail for his 40th birthday, Debs read Karl Marx’s Das Kapital, and though he never embraced Marxian Socialism, he grew to loathe competitive capitalism. Lincoln, not Lenin, remained his hero. But the rail-splitter’s America was gone, replaced by an economic system that Debs felt would have been unrecognizable to the Founders.

Debs emerged from jail more defiant than ever. An inspiring speaker, he energized a crowd of more than 100,000 in Chicago, denouncing capitalism and advocating for “the Spirit of ’76” and a system that allowed every worker “the opportunity to advance to the fullest limits of his abilities.” He was not a revolutionary, calling instead for workers to seize power through the ballot and reclaim the country that was rightfully theirs.

In 1897 he proclaimed himself a Socialist and founded the Socialist Party of America, injecting European-style class conflict into American politics.

Debs ran for president at the head of his party in 1900, receiving 96,000 votes; the total grew to 400,00 four years later. He ran again in 1908 and 1912, receiving 6 percent of the vote.

With the U.S. entry into World War I, the Federal government’s need for increased industrial production clashed headlong with the goals of Debs and organized labor. In the flurry of war-time patriotism, Congress passed the Espionage Act of 1917, designed to punish acts deemed disloyal, dangerous, and disruptive of the war effort. “I believe in free speech, in war as well as in peace,” Debs declared. “If the Espionage Law stands, then the Constitution of the United States is dead.” Flouting the law, Debs encouraged young American men not to fight: “The master class has always declared the wars, the subject class has always fought the battles.”

Federal authorities pounced. Prosecutor Edwin Wertz announced that “No man, even though four times the candidate of his party for the highest office, can violate the basic law of this land.” Debs was charged with violating the Espionage Act and convicted of sedition in 1918—and disfranchised for life. He was sentenced to three concurrent ten-year sentences. (Ironically, the same Act was used to charge Donald Trump in his handling of classified documents.)

Whether First Amendment martyr or war-time traitor, Eugene Debs found himself running as the Socialist candidate for president in 1920 from the Atlanta Federal prison. He told his supporters, who handed out photos of the candidate in convict denim, along with campaign buttons for “Prisoner 9653,” “I enter the prison doors a flaming revolutionist, my head erect, my spirit untamed and my soul unconquerable.” Despite the obvious impediments to his campaign and doubts about his eligibility, Debs received 915,000 votes for president—3.5 percent—the highest total the party ever won.

President Warren Harding finally released Debs—but did not pardon him—on Christmas Day 1921, and promptly invited him to the White House, where Debs’s charm was on full display. Fifty thousand supporters greeted him on his return to Indiana. But it was a pyrrhic victory, as prison nearly broke him. His health was ruined.

Debs died five years later, in 1926, at age 70, his dream and his cause in ruins. To this point, Eugene Debs remains the only presidential candidate to seek the office while imprisoned after a Federal conviction.