Notes from my recent reading….

“Spring and winter look ahead, autumn looks back, but summer is most at home in the here and now. It is nature’s extroverted season, seldom subtle. Air is dense and heavy. Shade becomes a hunger. Fields droop with green, and gardens lean under the weight. Heat oppresses and thunderstorms build like pressure in the body until warm rain washes the hot streets, leaving steam to rise like the memory of a fleeting passion.”

Marv and Nancy Hiles, Almanac for the Soul

“The seasons cannot be hurried. Spring comes, the grass grows by itself. Being in a hurry usually doesn’t help, and it can create a great deal of suffering—sometimes in us, sometimes in those who have to be around us. Scratch the surface of impatience and what you will find lying beneath it, subtly or not so subtly, is anger. It’s the strong energy of not wanting things to be the way they are and blaming someone (often yourself) or some thing for it.”

Jon Kabat-Zinn, Wherever You Go, There You Are

“Perhaps the truth depends on a walk around the lake. . .”

Wallace Stevens, “Notes Toward a Supreme Fiction vii”

“Many people are afraid of Emptiness because it reminds them of Loneliness. Everything has to be filled in, it seems—appointment books, hillsides, vacant lots—but when all the spaces are filled, the Loneliness really begins.”

Benjamin Hoff, The Tao of Pooh

“If there is anything I like less than lending a book, it is borrowing one, and I know no greater bore than the man who insists on lending you a book which you do not intend to read. You can cure him, ultimately, by losing the volume, but the process takes time.”

Edward Newton, A Magnificent Farce: And Other Diversions of a Book-Collector

“[James] Boswell asked Voltaire was it not more ‘pleasing and noble’ to believe the soul was immortal? Of course, Voltaire replied, but what of it? ‘You have a noble desire to be King of Europe. I wish it for you and I ask your protection. But it is not probable.’”

Robert Zaretsky, Boswell’s Enlightenment

“Thoreau’s Walden: a rather irritating collection of inspirational puffballs by an eccentric show-off.”

E. B. White, Essays of E.B. White

“Ten thousand engineers are busy making sure that the world shall be convenient even if it is destroyed.”

E. B. White, Essays

“I am aware that there is no Truth, no objective truth, no single truth, no truth simple or unsimple, either; no verity, eternal or otherwise; no Truth about anything, there are Facts, objective facts, discernible and verifiable. And the more facts you accumulate, the closer you come to whatever truth there is. And finding facts—through reading documents or through interviewing and re-interviewing—can’t be rushed; it takes time. Truth takes time.”

Robert Caro, Working: Researching, Interviewing, Writing

“Power doesn’t always corrupt, but what power always does is reveal.”

Robert Caro, Working

“The wet black velvet of a Southern night.”

Florence King, Confessions of a Failed Southern Lady

“She would give you half of anything she had to eat and three of everything she had to say.”

Florence King, Confessions of a Failed Southern Lady

“I never talked about Phineas and neither did anyone else; he was, however, present in every moment of every day. Finny had a vitality which could not be quenched so suddenly, even by the marrow of his bones.”

John Knowles, A Separate Peace

“Many years have passed since that night. The wall of the staircase, up which I had watched the light of his candle gradually climb, was long ago demolished. And in myself, too, many things have perished that, I imagined, would last forever…”

Marcel Proust, Swann’s Way: In Search of Lost Time, Volume 1

“If the stars should appear one night in a thousand years, how would men believe and adore; and preserve for many generations the remembrance of the city of God which has been shown!”

Ralph Waldo Emerson, “Nature,” Essays and Lectures

“Trust thyself: every heart vibrates to that iron string.”

Ralph Waldo Emerson, “Self-Reliance”

“All things have two handles, beware of the wrong one.”

Ralph Waldo Emerson, “American Scholar”

“They also serve who only stand and wait.”

John Milton, “On His Blindness”

“Shy, crumpled, middle-aged, and carrying with him the air of some unspoken defeat.”

Helen Macdonald, H is for Hawk

“A car drives past the field, and there are people in it, held securely on their way somewhere, wrapped in life like a warm coat.”

Helen Macdonald, H is for Hawk

“He was part of us and when he died, all the actions stopped dead and there was no one to do them just the way he did. He was individual. He was an important man. I’ve never gotten over his death. He shaped the world. He did things to the world. The world was bankrupted of ten million fine actions the night he passed on.”

Ray Bradbury, Fahrenheit 451

“Everyone must leave something behind when he dies, my grandfather said. A child or a book or a painting or a house or a wall built or a pair of shoes made. Or a garden planted. Something your hand touched some way so your soul has somewhere to go when you die, and when people look at that tree or that flower you planted, you’re there. It doesn’t matter what you do, he said, so long as you change something from the way it was before you touched it into something that’s like you after you take your hands away.”

Ray Bradbury, Fahrenheit 451

“May my course be bright, if it be but brief.”

Sir Walter Scott, The Talisman

“Whether a man is considered a saint or a troublemaking eccentric depends largely on circumstance.”

David Brion Davis, The Problem of Slavery in Western Culture

“Sometimes I wondered if

I had any faith.

I sat down and thought about it.

And when I had had enough

Of that I got up

And went on my way.

And that—the getting up

And going—was faith.”

Mary Jean Irion, Yes, World

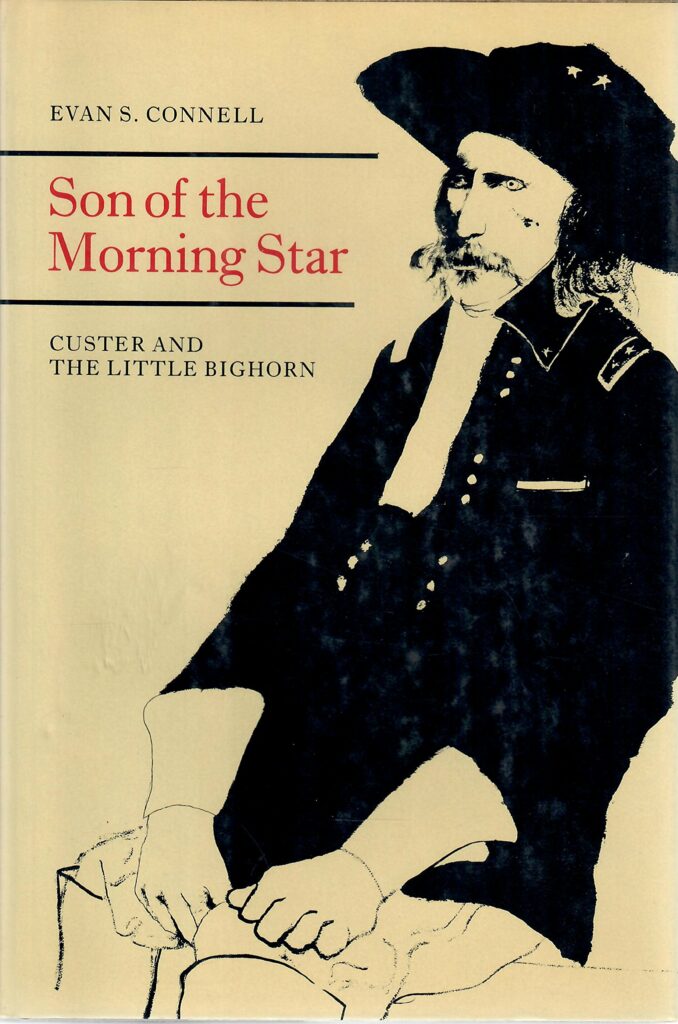

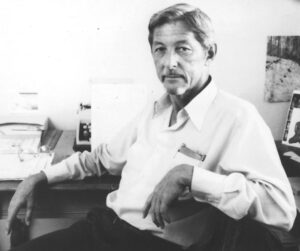

Item: Books, or A Case of Serendipity: I recently bought a copy of T.J. Stiles’s 2015 book, Custer’s Trials: A Life on the Frontier of a New America, which won the 2016 Pulitzer Prize for History. As I was putting it on the appropriate shelf in my office, I noticed immediately beside it my copy of Evan Connell’s 1984 best-seller on Custer, Son of the Morning Star, which has been hailed as a masterpiece. I remember buying the book as an undergraduate at UGA just getting interested in history. Why had I never read it? And who was Evan Connell? I remember reading articles in the mainstream media (like Time magazine) about how this unusual book and author surprisingly took the literary world by storm that year. I did the usual Google searches on Connell and found myself fascinated by what I discovered. Suffice it to say, Connell is considered a writer’s writer, at home in nearly every genre, from fiction, essays, and short stories, to history, biography, and poetry. The contemporary of Jack Kerouac, Philip Roth, and John Updike labored in comparatively undeserved obscurity, but hiding in plain sight was part of his deliberate brand. Connell, who died in 2013 at age 88, was a lifelong unmarried loner, the opposite of a self-promoter, who hated publicity and never courted the spotlight. He granted few interviews (none on camera) and if there’s a picture out there anywhere of him smiling, I’ve never seen it. He never did public readings of his work, never spoke publicly about his writing, never taught classes about writing or literature. He lived in the Bay Area much of adult life, spent some time in local watering holes, and formed few permanent attachments. He

Item: Books, or A Case of Serendipity: I recently bought a copy of T.J. Stiles’s 2015 book, Custer’s Trials: A Life on the Frontier of a New America, which won the 2016 Pulitzer Prize for History. As I was putting it on the appropriate shelf in my office, I noticed immediately beside it my copy of Evan Connell’s 1984 best-seller on Custer, Son of the Morning Star, which has been hailed as a masterpiece. I remember buying the book as an undergraduate at UGA just getting interested in history. Why had I never read it? And who was Evan Connell? I remember reading articles in the mainstream media (like Time magazine) about how this unusual book and author surprisingly took the literary world by storm that year. I did the usual Google searches on Connell and found myself fascinated by what I discovered. Suffice it to say, Connell is considered a writer’s writer, at home in nearly every genre, from fiction, essays, and short stories, to history, biography, and poetry. The contemporary of Jack Kerouac, Philip Roth, and John Updike labored in comparatively undeserved obscurity, but hiding in plain sight was part of his deliberate brand. Connell, who died in 2013 at age 88, was a lifelong unmarried loner, the opposite of a self-promoter, who hated publicity and never courted the spotlight. He granted few interviews (none on camera) and if there’s a picture out there anywhere of him smiling, I’ve never seen it. He never did public readings of his work, never spoke publicly about his writing, never taught classes about writing or literature. He lived in the Bay Area much of adult life, spent some time in local watering holes, and formed few permanent attachments. He  died alone in Santa Fe, New Mexico. And yet his novels reveal a remarkably penetrating insight into human relationships that are astonishing for someone who seemed to spend most of his life shunning them. His 1959 novel Mrs. Bridge (a National Book Award finalist) was praised as a masterpiece of spare, lean, concise story-telling, with not a spare word in it, as was his 1969 follow-up, Mr. Bridge. I bought and devoured them both and wished for more. I finally also read Son of the Morning Star (published by then-little-known North Point Press in Berkeley, now owned by FSG) and found it beautifully written and moving as well. The New York Times called it “impressive in its massive presentation of information” and added that “its prose is elegant, its tone the voice of dry wit, its meandering narrative skillfully crafted.” The Washington Post said it “leaves the reader astonished,” and the Wall Street Journal called it “a scintillating book, thoroughly researched and brilliantly constructed.” I can confirm that all of this is true. Happily, for people like me who are fascinated by him, there’s a new literary biography of Connell out by Steve Paul, Literary Alchemist: The Writing Life of Evan S. Connell, published in 2021 by the University of Missouri Press. And so, through the serendipity of shelving one book, Evan Connell is now on my list as a favored author whose writings I plan to work through patiently and in their entirety, one bite at a time. I’ll be spending considerable time with him in the coming years. If you love the power of words, I invite you also to get to know this talented, mysterious man in the only way we can—through his writing.

died alone in Santa Fe, New Mexico. And yet his novels reveal a remarkably penetrating insight into human relationships that are astonishing for someone who seemed to spend most of his life shunning them. His 1959 novel Mrs. Bridge (a National Book Award finalist) was praised as a masterpiece of spare, lean, concise story-telling, with not a spare word in it, as was his 1969 follow-up, Mr. Bridge. I bought and devoured them both and wished for more. I finally also read Son of the Morning Star (published by then-little-known North Point Press in Berkeley, now owned by FSG) and found it beautifully written and moving as well. The New York Times called it “impressive in its massive presentation of information” and added that “its prose is elegant, its tone the voice of dry wit, its meandering narrative skillfully crafted.” The Washington Post said it “leaves the reader astonished,” and the Wall Street Journal called it “a scintillating book, thoroughly researched and brilliantly constructed.” I can confirm that all of this is true. Happily, for people like me who are fascinated by him, there’s a new literary biography of Connell out by Steve Paul, Literary Alchemist: The Writing Life of Evan S. Connell, published in 2021 by the University of Missouri Press. And so, through the serendipity of shelving one book, Evan Connell is now on my list as a favored author whose writings I plan to work through patiently and in their entirety, one bite at a time. I’ll be spending considerable time with him in the coming years. If you love the power of words, I invite you also to get to know this talented, mysterious man in the only way we can—through his writing.

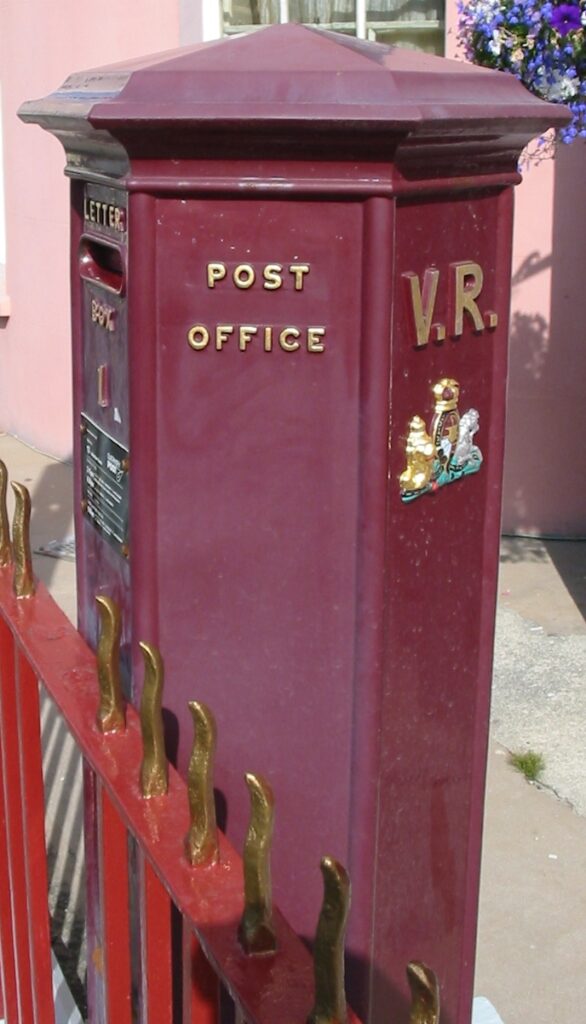

Item: Currently Reading: The Last Chronicle of Barset, by Anthony Trollope (originally published in 1867), the final volume (of 6) in the Barsetshire series that begins with The Warden (1855) then continues with Barchester Towers (1857), Doctor Thorne (1858), Framley Parsonage (1861), and The Small House at Allington (1864), chronicling the always interesting goings-on in the fictional county of Barsetshire and its cathedral town of Barchester during the height of the Victorian Era. The county is peopled with delightful almost-living characters like The Rev. Mr. Quiverful, Mrs. Proudie, Sir Omicron Pie, Dr. Fillgrave, Sir Abraham Haphazard, Sir Raffle Buffle, and many, many others. The series is beloved by Trollope fans, who are legion, ranging from actor Alex Guinness (Obi-Wan Kenobi), who never travelled without a Trollope novel, to economist John Kenneth Galbraith, to author Sue Grafton. It’s taken me 14 years to read the series, not because the books are hard to read—just the opposite; one critic said they’re like eating peanuts, hard to stop—but because I let too many years elapse between volumes. After this, it’s on to Trollope’s 6-volume Palliser series, which I hope to finish in half the time. Maybe I’ll read those straight through? At any rate, Trollope is also one of my favorite authors, not only for his wonderful books but because of how he wrote them. He famously kept to a disciplined schedule, putting in 3 hours at his writing desk every day before going to his real job at the Post Office, where he is credited with introducing the ubiquitous red pillar mailbox to the United Kingdom (seen here). His literary output was prodigious by any standards: 47 novels, 42 short stories, 5 travel books, 2 works of non-fiction, and an auto-biography. I intend to read them all.

Item: Currently Reading: The Last Chronicle of Barset, by Anthony Trollope (originally published in 1867), the final volume (of 6) in the Barsetshire series that begins with The Warden (1855) then continues with Barchester Towers (1857), Doctor Thorne (1858), Framley Parsonage (1861), and The Small House at Allington (1864), chronicling the always interesting goings-on in the fictional county of Barsetshire and its cathedral town of Barchester during the height of the Victorian Era. The county is peopled with delightful almost-living characters like The Rev. Mr. Quiverful, Mrs. Proudie, Sir Omicron Pie, Dr. Fillgrave, Sir Abraham Haphazard, Sir Raffle Buffle, and many, many others. The series is beloved by Trollope fans, who are legion, ranging from actor Alex Guinness (Obi-Wan Kenobi), who never travelled without a Trollope novel, to economist John Kenneth Galbraith, to author Sue Grafton. It’s taken me 14 years to read the series, not because the books are hard to read—just the opposite; one critic said they’re like eating peanuts, hard to stop—but because I let too many years elapse between volumes. After this, it’s on to Trollope’s 6-volume Palliser series, which I hope to finish in half the time. Maybe I’ll read those straight through? At any rate, Trollope is also one of my favorite authors, not only for his wonderful books but because of how he wrote them. He famously kept to a disciplined schedule, putting in 3 hours at his writing desk every day before going to his real job at the Post Office, where he is credited with introducing the ubiquitous red pillar mailbox to the United Kingdom (seen here). His literary output was prodigious by any standards: 47 novels, 42 short stories, 5 travel books, 2 works of non-fiction, and an auto-biography. I intend to read them all.