We received word here at GHS this week of the death of our dear friend Ed Jackson on Tuesday, January 10, 2023, age 79.

We received word here at GHS this week of the death of our dear friend Ed Jackson on Tuesday, January 10, 2023, age 79.

The Kingsport, Tennessee, native grew up in Texas, but it was the people of Georgia and their history that he made his life’s work.

Ed went to the University of Mississippi in the early 1960s and received his B.A. in History and an M.A. in political science. He put both of those to good use when, in 1970, he arrived in Athens at the University of Georgia and began a long and distinguished career at the Carl Vinson Institute of Government, retiring as Senior Public Service Associate 40 years later, in 2010.

During those 40 years Ed became the acknowledged expert, the man to ask about Georgia history and government. He trained governors, legislators, state employees, mayors, civic organizations, teachers, students, authored textbooks, spoke extensively, published widely, compiled databases, created over fifteen websites, photographed every corner of our state, and collected anything and everything that he could get his hands on about Georgia history, from postcards, to photographs, maps, artifacts of all kinds, campaign signs, and everything beyond and between that could tell the story of Georgia and her people.

Here’s what I said about Ed in the GHS’s Headlines newsletter yesterday: “Ed Jackson’s knowledge of Georgia’s people and history was unparalleled. He was Georgia’s unofficial state historian, and all of us beat a path to his door to dip into that deep reservoir of learning. There was no subject related to Georgia that he didn’t know something about, and that he would gladly and freely share. Every conversation with him left you wiser. He was also a great friend to this institution, through his membership, his time and resources, and the knowledge that he shared through his writing and research. The Georgia Historical Society is honored to be the repository of the Edwin Jackson Collection, ensuring that his documentary legacy will live on and that his vast collection of Georgia materials will continue to inspire and teach future generations. Though not born here, Ed Jackson was one of Georgia’s great treasures, and the people of this state that he served so long and so well are richer for all he taught us.”

When the Georgia flag-change controversy was at its height in the early part of this century, Ed was the go-to expert. He lectured on the history of our state’s flags for GHS in Athens and Savannah and published an article about it in the Georgia Historical Quarterly. And who else do you know that was awarded the “Vexillonnaire Award” by the North American Vexillological Association? Ed was, in 2004, for his work with the Georgia General Assembly’s efforts to redesign Georgia’s state flag. (Vexillogy is the study of flags, and no, I didn’t know that either.)

Ed had an extensive stamp collection (he was a founding member of the Georgia Federation of Stamp Clubs, now called the Southeast Federation of Stamp Clubs), and he once lectured here in our Research Center during the Georgia History Festival on Georgia history as told through stamps.

When the online New Georgia Encyclopedia needed an authority to write the entry for Georgia’s founder himself, James Edward Oglethorpe, they chose Ed. That forbidding subject would have daunted most historians, but not him. (That’s Ed in the center of the picture to the right, taking a photograph at Oglethorpe’s tomb in England.) For good measure, he also wrote seven other entries for the NGE, including for Georgia’s Historic Capitals, the Dixie Highway, Georgia’s State Flags, the current Georgia State Capitol, and the Legislative Process. He also served as a section editor for the NGE.

When the online New Georgia Encyclopedia needed an authority to write the entry for Georgia’s founder himself, James Edward Oglethorpe, they chose Ed. That forbidding subject would have daunted most historians, but not him. (That’s Ed in the center of the picture to the right, taking a photograph at Oglethorpe’s tomb in England.) For good measure, he also wrote seven other entries for the NGE, including for Georgia’s Historic Capitals, the Dixie Highway, Georgia’s State Flags, the current Georgia State Capitol, and the Legislative Process. He also served as a section editor for the NGE.

Every time I called Ed and needed help, he was always happy to assist, whether it was asking him to write an article for GHS’s Georgia History Today popular history magazine (where he wrote about the Dixie Highway, FDR in Georgia, and any number of his other passions), querying him about a fact on a proposed historical marker, or to answer one of my many arcane questions about Georgia history. He was never too busy, he never said no, and he never took a dime for all he did for GHS. If he could help further the mission of Georgia history, he would.

It’s no exaggeration to say that we would not have been able to do “Today in Georgia History” in conjunction with Georgia Public Broadcasting without Ed Jackson. It was his website, “GeorgiaInfo,” created for the Vinson Institute, that provided a roadmap for all the subjects we’d cover day to day over the course of the year. Naturally, he made it all available to us—and to everyone else—without any desire for personal credit. He only wanted to teach Georgia history, and if his website helped GHS and GPB do that, then he was glad to help.

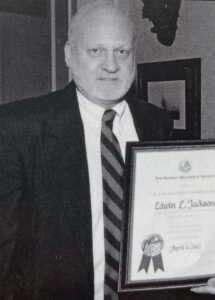

GHS honored Ed in 2002 with the John MacPherson Berrien Award for Lifetime Achievement in Georgia history (pictured here), and in 2012 with the Sarah Nichols Pinckney Volunteer Award.

GHS honored Ed in 2002 with the John MacPherson Berrien Award for Lifetime Achievement in Georgia history (pictured here), and in 2012 with the Sarah Nichols Pinckney Volunteer Award.

Ed donated his vast and extraordinary collection of materials related to Georgia history to the GHS just a couple of years ago. The Edwin Jackson Collection at the Georgia Historical Society is now being processed, and when completed and opened for research it will be a treasure trove of riches that will be mined for decades to come.

Thank you, Ed, for all your years of self-less service to others, in the finest tradition of Non Sibi, Sed Aliis, Not for Self, But for Others, harkening back to the original Georgia Trustees. Thank you for your years of friendship to the Georgia Historical Society, to the University of Georgia, to the State of Georgia and her people—including all those yet unborn. They too are in your debt. Thanks to you, the path forward will be brighter for all those who look to the past to help light the way.

Georgia never had a better friend than this adopted son, and he will be deeply missed. He is quite irreplaceable.

We salute you, and farewell.

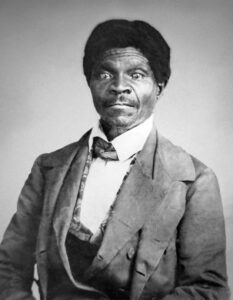

The Supreme Court’s decision was highly anticipated—and was leaked before the Court’s announcement. The Court would be ruling on the most contentious issue of the age, one that had threatened to tear the country apart for decades. When it was announced, one side hailed it as the final word on a divisive subject, finally laying the issue to rest. The other side exploded in moral outrage, charging the court with action far beyond its jurisdiction by trying to solve a complex and difficult political issue, overturning a long-standing precedent, and vowed to disregard the ruling and take the appeal directly to the American people.

The Supreme Court’s decision was highly anticipated—and was leaked before the Court’s announcement. The Court would be ruling on the most contentious issue of the age, one that had threatened to tear the country apart for decades. When it was announced, one side hailed it as the final word on a divisive subject, finally laying the issue to rest. The other side exploded in moral outrage, charging the court with action far beyond its jurisdiction by trying to solve a complex and difficult political issue, overturning a long-standing precedent, and vowed to disregard the ruling and take the appeal directly to the American people.