The Great Gatsby, by F. Scott Fitzgerald (Scribner, 1925, 180 pp.)

The Great Gatsby, by F. Scott Fitzgerald (Scribner, 1925, 180 pp.)

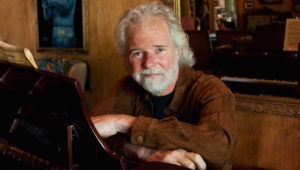

Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald is one of those artists whose tragic life has become in some ways more famous than his creations.

He was a founding member of the Lost Generation of (mostly) expatriate writers who flourished in the 1920s and ’30s, and who have been endlessly romanticized and criticized, particularly in Ernest Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast.

Fitzgerald’s meteoric rise after the publication of This Side of Paradise in 1920, his stormy marriage to Zelda and her descent into madness, his rocky friendship with Hemingway, his close partnership with editor Maxwell Perkins, his alcoholism and depression, and his last frantic scriptwriting hack days in Hollywood are all well-known and well-documented. When he died of a heart attack four days before Christmas in 1940 (at age 44, like Robert Louis Stevenson), with his last novel only half-finished, he considered himself a literary failure who would quickly be forgotten.

But a funny thing happened on the way to obscurity. His third novel, The Great Gatsby, had never sold particularly well in his own lifetime—in the first year Scribner’s sold only 20,000 copies—and was considered nothing more than a 1920’s period piece. Then during World War II the paperback version became enormously popular with soldiers stationed abroad, and in the post-war years it was added to high-school curricula across the country. Suddenly it was re-evaluated as a towering classic of American 20th-century fiction, and sales skyrocketed. It has now sold over 25 million copies (including about half a million worldwide annually) and remains Scribner’s most popular title. If only Fitzgerald had lived to see even a bit of it.

Mercifully, I was never required to read it in high school, because if I had, I would have brought a 17-year-old’s sensibilities to a great piece of literature, and it would have been wasted on me. Now was my time to read it. Harrumph alert: It irritates me to no end when I hear grown, mature adults wave off reading a great book because “I read it in high school,” or, when I tell them what I’m reading, ask “Didn’t you read that in high school?”

The Encyclopedia Britannica calls Gatsby “the most profoundly American novel of its time.” The Modern Library in 1998 voted it the 20th century’s best American novel and the century’s second-best English-language novel, behind only—if you can believe it—Ulysses.

Is Gatsby worthy of all the praise? In the immortal words of James I. “Bud” Robertson, Jr., “oh my yes.”

It’s a novel that works on and in you, that will continue to make you ponder just what was going on in it for a good long while after you’ve put it back on the shelf. I just finished it, and I’d like to re-read it already, and that’s not something I say very often. If I were writing a novel, I’d study it and use it as a model for what a writer can do with plot, a few characters (and there aren’t many) and pacing, using spare, lean language that says more than you think it does, all in 180 pages.

The book was written when Fitzgerald was just 29 years old . One can only marvel at his felicity with language at so young an age:

“The bored haughty face that she turned to the world concealed something—most affectations conceal something eventually, even though they don’t in the beginning—and one day I found out what it was.”

“There are only the pursued, the pursuing, the busy, and the tired.”

“The evening had made me light-headed and happy; I think I walked into a deep sleep as I entered my front door.”

“No amount of fire or freshness can challenge what a man will store up in his ghostly heart.”

“There is no confusion like the confusion of a simple mind.”

It was a literary feat that proved hard to live up to, much less repeat. Fitzgerald spent the last sloshy 15 years of his life pitifully trying to recreate the magic. He did not know that he had already achieved literary immortality:

“They were careless people, Tom and Daisy—they smashed up things and creatures and then retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness, or whatever it was that kept them together, and let other people clean up the mess they had made.”

Finally: “So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.”

Those last words adorn Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald’s grave in Baltimore, a fitting literary blanket under which to slumber, marking two lives that ended much too soon.