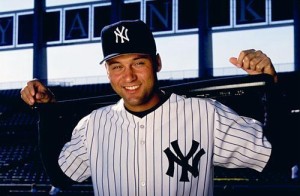

Six months ago in this space I lamented the end of the baseball season. Now, with the arrival of April and the return of Spring and the national pastime, it’s only fitting that we remember the Georgia native who made history in 1947 by being The First.

Six months ago in this space I lamented the end of the baseball season. Now, with the arrival of April and the return of Spring and the national pastime, it’s only fitting that we remember the Georgia native who made history in 1947 by being The First.

For most of us, being first is something we long for. Americans like being first in everything—first means gold medals, it means winning, it means recognition, it means an association with being the best, with something good. First in line; first-come, first-served. The first in our class. First edition. The first to climb Mount Everest. First in the polls. First in war, first in peace, first in the hearts of his countrymen. The first sign of spring. The first time ever I saw your face. The first kiss, the first dance, the first date, the first to walk on the moon. The first day of the year. The first. Number one.

But what if being first means having people hate your guts? What if going to work every day meant you were open to taunts, threats, and physical violence? And what about volunteering to be the first at something you know is going to be the hardest road you’ve ever walked down in your life? Why would you do it? Would you do it? Honestly, most of us would say, let this cup pass from me. We are reminded of William Shakespeare’s great lines: Some are born great; some achieve greatness; some have greatness thrust upon them.

After World War II, Brooklyn Dodgers president and general manager Branch Rickey was looking for a way to put more fannies in the seats at Dodger games and to make his team better. Every team president wanted to do that. But the other thing Rickey had in mind seemed downright radical and, some thought, un-American. He wanted to break baseball’s color barrier and put a black baseball player on the Brooklyn Dodgers. A dangerous piece of social engineering, to be sure. To give you some perspective, that same year, 1947, the Memphis Censorship Board banned the movie Curley because it showed black and white children playing together. If you thought opposition to health care reform was intense, what Rickey wanted to do seemed unimaginable. There had been an unofficial “gentlemen’s agreement” against such a thing since the nineteenth century. But Branch Rickey, a man born in the late nineteenth century in Ohio, thought it was a good idea.

Who would he sign? It would take a rare individual; it had to be someone with a relentless personality and a determined drive to succeed. Someone who could take the most vile abuse imaginable and turn the other cheek. Someone who could psychologically endure loneliness and extreme public persecution while simultaneously being a very good baseball player. History had summoned Jack Roosevelt Robinson.

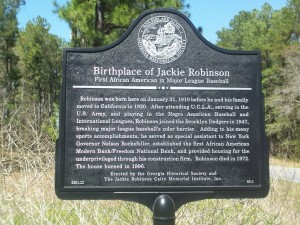

Robinson was born in Cairo, Georgia, on January 31, 1919. Abandoned by her husband, his mother Mallie moved the family to Pasadena, California, in 1920, and Robinson attended John Muir Technical High School and Pasadena Community College before transferring to the University of California, Los Angeles. At UCLA he was an outstanding athlete, lettering in four sports—baseball, football, basketball, and track—and he excelled in swimming and tennis as well. Jackie Robinson was used to competing at the highest level of competition, and he was no shrinking violet. Scott Simon called him “a hard-nosed, hard-assed, brass-balled, fire-breathing athlete.”

Robinson was born in Cairo, Georgia, on January 31, 1919. Abandoned by her husband, his mother Mallie moved the family to Pasadena, California, in 1920, and Robinson attended John Muir Technical High School and Pasadena Community College before transferring to the University of California, Los Angeles. At UCLA he was an outstanding athlete, lettering in four sports—baseball, football, basketball, and track—and he excelled in swimming and tennis as well. Jackie Robinson was used to competing at the highest level of competition, and he was no shrinking violet. Scott Simon called him “a hard-nosed, hard-assed, brass-balled, fire-breathing athlete.”

Robinson showed early that he was not afraid to stand up to bigotry. He was drafted in 1942 and served on military bases in Kansas and Texas. With help from boxer Joe Louis, he succeeded in opening an Officer Candidate School for black soldiers. Soon after, Robinson became a second lieutenant. Late one evening at Fort Hood, Texas, Robinson got on a bus and spotted a fellow officer’s light-skinned wife who could easily be mistaken for white; he sat down next to her. The bus driver stopped the bus and yelled out, “Hey boy! Get to the back of the bus!” Robinson refused and faced a court martial. When a private at MP headquarters later that evening asked Robinson if he was “the nigger lieutenant” who had gotten in trouble, Jackie told him, “If you ever call me a nigger again, I’ll break you in two.” In the end, the order was ruled a violation of Army regulations, and he was exonerated. Shortly after leaving the Army in 1944, Robinson joined the Kansas City Monarchs, a leading team in the Negro Leagues.

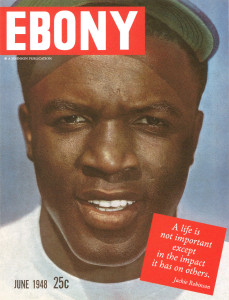

When Branch Rickey signed Jackie Robinson and finally brought him up to the big leagues in the spring of 1947, baseball’s “Great Experiment,” as it was called, electrified America. Probably the only rookie given a day in his honor, Robinson trailed only Bing Crosby in a year-end national popularity poll. Virtually the entire black population of America became Dodger fans. At the end of the season, Robinson had been named the league’s Rookie of the Year (an award that now bears his name), gaining respect throughout the baseball world and beyond. Three years later he won the batting title, hitting .346, was named Most Valuable Player, and led the Dodgers to the World Series. Over a ten-year career he hit .311, and played in six all-star games and six World Series. He was voted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1962.

When Branch Rickey signed Jackie Robinson and finally brought him up to the big leagues in the spring of 1947, baseball’s “Great Experiment,” as it was called, electrified America. Probably the only rookie given a day in his honor, Robinson trailed only Bing Crosby in a year-end national popularity poll. Virtually the entire black population of America became Dodger fans. At the end of the season, Robinson had been named the league’s Rookie of the Year (an award that now bears his name), gaining respect throughout the baseball world and beyond. Three years later he won the batting title, hitting .346, was named Most Valuable Player, and led the Dodgers to the World Series. Over a ten-year career he hit .311, and played in six all-star games and six World Series. He was voted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1962.

It sounds like he won American Idol, doesn’t it? But this is to sum up a year and a career, and we don’t live our lives like that. We live out each minute and each hour, sometimes in excruciating pain. For Jackie Robinson, 1947 was an entirely different experience, a hell on earth.

The kind of public torture that Jackie Robinson faced few of us, thank goodness, will ever know. We all remember the public humiliation we felt and the laughter we faced from our peers when our mothers made us wear raincoats to school or take an umbrella on days when it rained, or when she made you wear a tie to school on picture day. And while few things in life equal the scorn of tormenting 13-year-olds whose approval you would desperately like to have, for most of us that’s as bad as it will ever get. But the rites of passage we all knew in our adolescence are not what I’m talking about. I’m talking about the special level of hell reserved for those first black students who walked up the steps that morning at Little Rock Central High School in 1957. For the first former slave who walked to a polling place and told a white man that he was there to vote after the Civil War. For the first women who attended law schools. This is the kind of first that Jackie Robinson volunteered for.

In a now-legendary meeting, Dodgers GM Branch Rickey confronted Robinson with the wide range of abuse he knew Robinson would face. Robinson listened to Rickey talk, growing visibly angry, and finally blew up. “Do you want a player afraid to fight back?” he shouted. Rickey replied no, that he wanted someone even tougher than that, someone, he said, “with the guts not to fight back.” Restraint would be the measure of his courage. Rickey told him, “Jackie, we’ve got no army. There’s virtually nobody on our side. No owner, no umpires, very few newspapermen. And I’m afraid that many fans may be hostile. We’ll be in a tough position. We can win only if we can convince the world that I am doing this because you’re a great ballplayer, and a fine gentleman. You cannot fight back.” He told Robinson, “I need someone who can carry this load.” Robinson agreed that for three years, he wouldn’t fight back. He wouldn’t speak up. He wouldn’t argue. He would simply take it, and all the while he would try to perform at the highest level. Failure wasn’t an option.

Many thought Rickey would pick the great Satchel Paige, and when he wasn’t chosen reporters sought him out. Was he bitter or disappointed? No, Paige said with enormous class, “They didn’t make a mistake by signing Robinson,” he told them. “They couldn’t have picked a better man.” In Scott Simon’s words, Rickey had anointed a knight to ride out first.

But being first means being a target, and it began with members of his own team. In spring training, Dodgers manager Leo Durocher had to squelch plans for a players’ petition against Robinson in a midnight meeting. But when some Dodgers actively protested against Robinson, Durocher stood up to them: “Listen, I don’t care if this guy is white, black, green or has stripes like a f’ing zebra. If I say he plays, he plays. He can put an awful lot of f’ing money in our pockets. Take your petition and shove it up your ass. This guy can take us to the World Series, and so far we haven’t won spit.”

When the team went on the road in spring training, Robinson had to stay in different hotels, separate from the rest of the team, and eat in different dining rooms. And always he was alone. The famous Dodgertown complex later erected was in part a response to the problems that Robinson and other blacks faced with spring-training racism. His teammates kept their distance in the dugout and on the field. One sportswriter said that Jackie Robinson looked to him, sitting in the dugout all by himself, away from his teammates, like the loneliest man in the world. He knew that nearly everyone wanted to see him fall flat on his face, to make a fool of himself, and of Branch Rickey, who was accused of being a communist and a socialist. After the start of the season, the St. Louis Cardinals were rumored to be planning a strike in protest of Robinson. Vile insults and black cats were thrown at him from the stands in St. Louis. Some of the worst abuse came from players on opposing teams.

The Phillies were managed by Ben Chapman from Alabama, and he told his players that when Robinson came to bat, to open up with both barrels, to taunt and bait Robinson with all they had, “to see if he can take it.” Hitting a major league curveball is considered one of the most difficult of all athletic achievements. Imagine trying to do it while hearing things like this coming from the opposing dugout:

“Hey nigger! That ball ain’t no watermelon boy!”

“You can’t play with white boys, you know that! Get back to the jungle, nigger boy!”

“Hey nigger, why don’t you go back to the cotton field where you belong?”

“Hey, snowflake, which one of those white boys’ wives are you dating tonight?”

“We don’t want you here, nigger!”

We can wonder now how anyone could have been so ignorant. Or how he could have endured it. There were references to thick lips, thick skulls, and syphilis sores. The stands rained down with tomatoes, rocks, watermelon slices, Sambo dolls, and the most vile things you could ever say to another human.

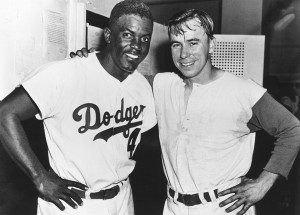

It did something even to his own teammates, who for the most part had left him alone, had kept their distance. Dodger Eddie Stanky—also from Alabama—had enough. He stood up on the dugout steps and called Chapman a coward and told him to pick on someone who could fight back. In Cincinnati, Dodger shortstop Pee Wee Reese,a native of Louisville, Kentucky, put his arm around Robinson’s shoulder to show his support for his teammate. A small thing, really, but a hugely symbolic moment that was lost on no one and meant the world to Robinson.

It did something even to his own teammates, who for the most part had left him alone, had kept their distance. Dodger Eddie Stanky—also from Alabama—had enough. He stood up on the dugout steps and called Chapman a coward and told him to pick on someone who could fight back. In Cincinnati, Dodger shortstop Pee Wee Reese,a native of Louisville, Kentucky, put his arm around Robinson’s shoulder to show his support for his teammate. A small thing, really, but a hugely symbolic moment that was lost on no one and meant the world to Robinson.

There were other moments, with other teams. In Pittsburgh, Robinson and the great Hank Greenberg, who was Jewish and had been called vile names himself, collided on a violent play at first and Robinson was called safe. It was a tense moment. They each got up, dusted themselves off, and as Robinson took his lead off first base, he heard Greenberg say behind him, “Stick in there. You’re doing fine. Keep your chin up.” After the game, Robinson told a reporter, “Class sticks out all over Mr. Greenberg.”

As Branch Rickey later remembered, racists like Chapman actually brought the Dodgers together as nothing else could. “He solidified and unified thirty men, not one of whom was willing to sit by and see someone kick a man who had his hands tied behind his back.” Incidentally, Jackie Robinson scored the only run that day. The Dodgers beat Chapman’s Phillies 1-0. God does have a sense of humor.

He said later that that day almost broke him. For one moment, he remembered, he thought, “to hell with this.” “I was, after all, a human being. What was I doing here turning the other cheek as though I weren’t a man?” Robinson said he wanted to “stride over to that Phillies dugout, grab one of those white sons of bitches, and smash his teeth with my despised black fist.”

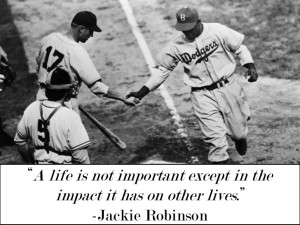

That Jackie Robinson had to go through something like that just to play a game is shameful, but it gives us some insight into the character of the man that he endured it, bore it with grace and dignity, and thrived in spite of it. He stood there and took it, and he did it, he said later, for his mother who had kept his family together after being abandoned by his father, for his brothers who never got this kind of chance, for Branch Rickey who displayed enormous courage himself, and for all the ones who would come after him. It was for good reason that much later his daughter Sharon wrote a children’s book about him entitled Testing the Ice, which he did both literally and metaphorically. This was a man whose life provided a foundation upon which so many others would build. Willie Mays said later that every time he looked at his house he thanked God for Jackie Robinson.

After three years, Robinson pushed back. He argued with umpires, he protested second-class accommodations, and no one ever taunted him to his face. But having to internalize all of it killed him, quite literally. He was dead by 53. It is his name we remember today, and not those of the small men who taunted him.

This is what makes history so fascinating to me: you can read all day about how depraved humans as a species have been, but then you come across someone who inspires you by simple acts of courage and dignity. Jackie Robinson was not a great military hero or politician; he never took a city by force, never won an election, never conquered an army, never explored unknown lands, never founded a colony. He never started a war or ended one. Nor was he a saint. No man is. He was just a baseball player, albeit a great one; but he was so much more than that. As someone once said, it didn’t take a great baseball player to break down that barrier. It took a great man.

This is what makes history so fascinating to me: you can read all day about how depraved humans as a species have been, but then you come across someone who inspires you by simple acts of courage and dignity. Jackie Robinson was not a great military hero or politician; he never took a city by force, never won an election, never conquered an army, never explored unknown lands, never founded a colony. He never started a war or ended one. Nor was he a saint. No man is. He was just a baseball player, albeit a great one; but he was so much more than that. As someone once said, it didn’t take a great baseball player to break down that barrier. It took a great man.

Even if she never likes baseball—and she will—I want my daughter to know about Jackie Robinson. I want her to learn that many things she might take for granted were achieved only with great sacrifice and at a very high cost, and that she will have opportunities in her life—to vote, to go to college, perhaps attend law school, become a doctor, a CEO, a writer, a soldier, a teacher, a baseball player—because someone else opened a door that was closed and carried the weight of being first upon their shoulders. And should she herself ever be called upon one day to step forward and be the first in some field or endeavor, she could have no better example of how to walk a difficult and lonely yet dignified path than the life of Jackie Robinson.

Robinson was a brave and courageous man, one of those rare souls who, when the great question is asked, “who will go first?” didn’t avert his eyes, put his head down, or walk away. He stepped forward and said, “I will.” When he took the field on April 15, 1947, and kept taking it, day after day, he didn’t just make the Dodgers better. He made the human race better. “I’m not concerned with your liking or disliking me,” he said, “all I ask is that you respect me as a human being.”

Robinson was a brave and courageous man, one of those rare souls who, when the great question is asked, “who will go first?” didn’t avert his eyes, put his head down, or walk away. He stepped forward and said, “I will.” When he took the field on April 15, 1947, and kept taking it, day after day, he didn’t just make the Dodgers better. He made the human race better. “I’m not concerned with your liking or disliking me,” he said, “all I ask is that you respect me as a human being.”

Play ball.