December 21 marks the anniversary of the end of General William Tecumseh Sherman’s March to the Sea, the surrender of Savannah to United States armed forces during the Civil War, and Sherman’s Christmas “gift” of Savannah to President Abraham Lincoln. Sherman’s March was also an important part of the history of emancipation. This Dispatch examines that controversial event and its legacy in American history.

Category Archives: Public History

The Law of Unintended Consequences

The Supreme Court’s decision was highly anticipated—and was leaked before the Court’s announcement. The Court would be ruling on the most contentious issue of the age, one that had threatened to tear the country apart for decades. When it was announced, one side hailed it as the final word on a divisive subject, finally laying the issue to rest. The other side exploded in moral outrage, charging the court with action far beyond its jurisdiction by trying to solve a complex and difficult political issue, overturning a long-standing precedent, and vowed to disregard the ruling and take the appeal directly to the American people.

The Supreme Court’s decision was highly anticipated—and was leaked before the Court’s announcement. The Court would be ruling on the most contentious issue of the age, one that had threatened to tear the country apart for decades. When it was announced, one side hailed it as the final word on a divisive subject, finally laying the issue to rest. The other side exploded in moral outrage, charging the court with action far beyond its jurisdiction by trying to solve a complex and difficult political issue, overturning a long-standing precedent, and vowed to disregard the ruling and take the appeal directly to the American people.

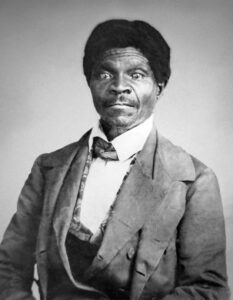

Sound familiar? It was March 6, 1857, and the case was Dred Scott v. Sanford. It has often been called by historians “the worst Supreme Court decision ever handed down.”

Dred Scott was an enslaved man who lived in Missouri (a slave state) with an Army surgeon, Dr. John Emerson. Emerson took Scott to the free state of Illinois and then on to the free territory of Wisconsin, where Scott married his wife, Harriet Robinson. Four years later they returned to Missouri with Emerson. After Emerson’s death, his widow refused to sell the Scotts their freedom. With the help of anti-slavery lawyers, Scott sued, claiming that his residence in Illinois and Wisconsin meant that he was free. The case worked its way through state courts. Mrs. Emerson eventually transferred Scott’s ownership to her brother, John Sanford, who lived in New York state, moving the suit into Federal jurisdiction. The case finally made its way to the Supreme Court, presided over by Chief Justice Roger Taney of Maryland.

Missouri applied for statehood in 1820 as a slave state, which would have upset the Congressional balance of power between free and slave states. Maine came in as a free state at the same time, but Congress, passing the Compromise, ruled that all future territories west of Missouri and north of Missouri’s southern border at latitude 36°30′ would be free. The Missouri Compromise had held for 37 years, even as the agitation over slavery in the western territories had fiercely divided the country.

The Taney Court, in a 7-2 decision, handed down its decision on March 6, just two days after pro-slavery Pennsylvania Democrat James Buchanan’s inauguration as the 15th president.

Taney could have ruled that Scott, being Black and enslaved, was not due his freedom and left it at that. But Taney went much further, ruling that Black Americans—whether enslaved or free—were not citizens, had never been citizens, and would never be, ignoring the precedent that African Americans were citizens in several states already. Not being citizens, he ruled, they had no standing to sue in any court in the United States and in fact had “no rights which any white man is bound to respect.”

Again, Taney and his majority could have stopped there. But Taney wanted to put an end to the acrimonious debates threatening to rend the Union asunder. He ruled that the Missouri Compromise of 1820 forbidding slavery in the western territories had been unconstitutional, that Congress never had the right to forbid or abolish slavery in any territory. Slavery followed the flag.

Associate Justice James Moore Wayne of Georgia played a large role in pushing the Court to go farther than simply issuing a narrow ruling. Hoping that the Court could do what politicians seemingly could not—settle the slavery question for good—Wayne was instrumental in persuading the Court to rule the Missouri Compromise unconstitutional, and his concurring opinion went farther in supporting Taney’s than any other justice’s.

The White South embraced the decision as an answered prayer while a storm of anger swept across the North. Georgia’s Robert Toombs bragged that he would call the roll of his slaves under Boston’s Bunker Hill Monument, while abolitionists exploded in outrage when they read newspaper headlines that boasted, “The Triumph of Slavery Complete.” Northern Free-Soilers and champions of popular sovereignty—the right of citizens in each territory to decide the issue for themselves—thought the ruling a blow against democracy. Ultimately the decision split the Democratic Party into irreconcilable factions while uniting the nascent Republican Party in opposition to what it considered an outrageous case of judicial overreach that had no moral validity and insulted freedom-loving Americans everywhere.

The decision proved to be a disaster for the Supreme Court and the proslavery advocates who celebrated it. The Court’s reputation was damaged, and far from quelling the slavery issue, the decision backfired, pushing the country ever closer to Civil War. That conflict did exactly what Taney had denied possible: It destroyed slavery and, through the Reconstruction amendments, made citizens of the formerly enslaved, in the process forever altering the relationship between the Federal government and the American people.

The Black struggle for full citizenship during the era of Emancipation and Reconstruction would lead to the great Civil Rights revolutions of the 20th century—and, ironically, the heavily politicized Dred Scott case helped pave the way.

Podcast S6E2: Johann Neem: History and Democracy

In this episode Stan interviews Dr. Johann Neem, historian and author, whose research focuses on the history of American democracy. They discuss history in the public realm, why history has become so controversial in recent years, and where it’s all headed.

Dispatches from Off the Deaton Path: Veterans Day

Stan explores the origins of Veterans Day 100 years in the aftermath of World War I, and how Savannah has honored and memorialized those who served and died for their country.

The Freshest Advices

Hello again. It’s been 8 months since I last spoke to you directly in this space, and a lot has happened since then. A lot. War in Ukraine. A landmark court case. Historic Congressional committee hearings. Divisive legislation in state houses across the country. FBI searches. Monkey pox. The University of Georgia won the College Football National Championship. The Major League Baseball season began. Our beloved Braves are winning though still underperforming. Better Call Saul is ending. I discovered honest-to-goodness Keto bread at the Red and White.

Much has also happened at the Georgia Historical Society, and I hope you’ve enjoyed reading on this blog about some of the great scholars who have been visiting our newly renovated and expanded Research Center and the interesting projects they’re working on. We’ll continue to do that from time to time.

There’s a lot to catch up on regarding history in the public arena, and I hope to do that in this space very soon. To say that we live in interesting times would be an understatement.

For now, besides re-introducing myself here, I would be remiss if I didn’t note two recent deaths, one quite well known, the other less so but equally deserving.

Just this week, on August 7, we lost David McCullough, one of our very finest public historians, whose work in print and on television touched millions over the last 50 years. The large pile of books that he click-clacked out of his 1940 Royal manual typewriter in his small writing shed on Martha’s Vineyard were all deeply researched, beautifully written, and magisterial in scope. Two won Pulitzer Prizes. Every word was written for the public, not other scholars, and few practitioners of Clio’s craft did it as well as he. He proudly carried on the tradition of William Prescott, Francis Parkman, George Bancroft, Esther Forbes, Margaret Leech, Allan Nevins, and Bruce Catton. He will be sorely missed.

On July 29 Fred Mingledorff died, one of the last surviving combat veterans of World War II living here in Savannah (or anywhere else, for that matter). Three years ago, on the 75th anniversary of the invasion of Guam, in which he fought, I had the privilege of interviewing him for a podcast. He shared his vivid memories and nightmares about The War and his hopes and fears for the future. He had earlier donated to the Georgia Historical Society many of the artifacts he brought home as a US Marine from the Pacific, now preserved for educating future generations . It was honor to know this gentle, kind man, beloved by his family, friends, and the community that he served so long and so well. Fred Mingledorff, Marine Corps veteran, one of our last living links to the generation that saved the world in the darkest period of history, lived to be 98. Well done, sir. Semper Fi.

My long disappearance from this space may have prompted you to fear or hope that I had gone to seed somewhere, never to return, moldering blissfully away glass in hand, whiskey-sodden in a malaria-infested backwater or mountain-top aerie. No such luck for you. As this blog has attested over the previous months, work here at GHS has been busy, and summer hiatus is now over. Long-suffering readers will once again be afflicted with blogs, podcasts, videos, book and movie reviews, articles about history and sports, food, or whatever else is on my mind.

Stay tuned and stay safe, and as always, thank you for reading.