This first appeared as an editorial in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution on Monday, February 19, 2024.

Percy Shelley wrote that power poisons every hand that touches it. History is littered with the names of those who attained power ruthlessly, wielded it arbitrarily, and refused to give it up.

Percy Shelley wrote that power poisons every hand that touches it. History is littered with the names of those who attained power ruthlessly, wielded it arbitrarily, and refused to give it up.

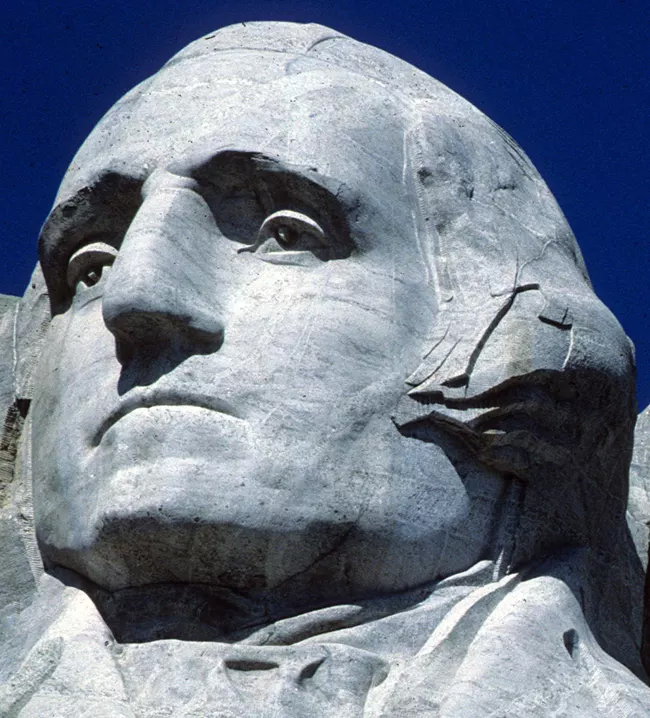

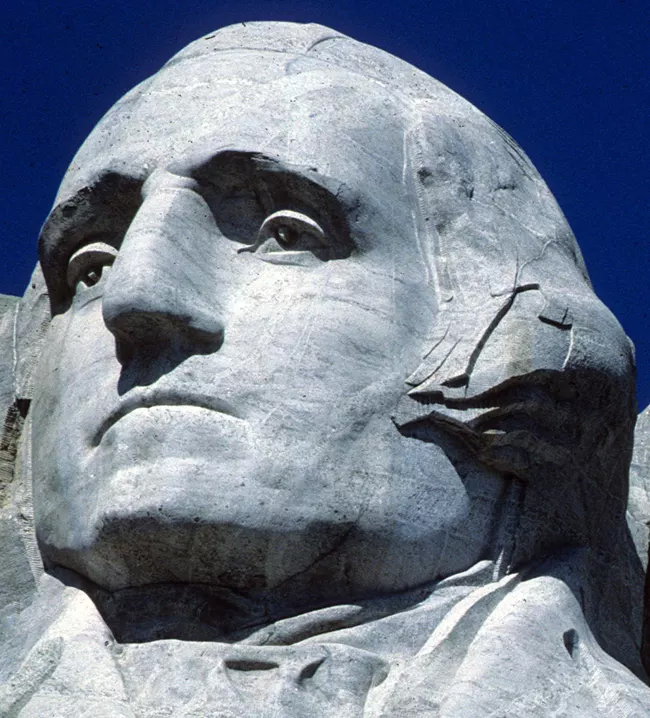

In one of history’s most famous stories, King George III asked the American painter Benjamin West what George Washington would do after winning independence. West replied, “They say he will return to his farm.” King George was incredulous: “If he does that, he will be the greatest man in the world.”

At the end of the American Revolution, George Washington rode to Annapolis, Maryland, where Congress was in session, to resign the commission he had accepted in June 1775, eight years earlier.

Consider what he was doing. Congress had vested full military authority in Washington to lead the Continental Army as commander in chief, and he had done so for the duration of the conflict. At least twice toward the end of that period, however, he was encouraged by others to seize power as dictator.

The Confederation Congress was weak and had virtually no ability to raise revenue to pay its expenses, chief among them the back pay of soldiers and officers of the Continental Army, months in arrears. Now was the time for Washington to strike.

On May 22, 1782, Washington received a letter from Colonel Lewis Nicola of Pennsylvania, proposing that Washington seize power with the help of the army and declare himself dictator or king. It had apparently been talked about for some time. Nicola was proposing nothing less than a military coup.

Revolutions often dissolve into dictatorships. Chaos breeds the conditions for a strong man to seize power, claiming to have all the answers and authority to solve complex problems. For many people this was where the road of self-government always ended. Why should the American Revolution have been any different?

If there was ever a moment in American history when one individual could have felt justified in seizing power and doing the unthinkable, that was it. There was no central government, no executive branch, no federal bureaucracy, no Supreme Court, and he was head of the national army. Washington could not be charged with acting unconstitutionally because there was no Constitution. Rule of law? Washington could have been the law.

No. Washington responded to Nicola with scorn and contempt. “Be assured, Sir, no occurrence in the course of the war has given me more painful sensations than such ideas existing in the Army as you have expressed, and I view them with abhorrence and reprehend with severity. I am at a loss to conceive what part of my conduct could have given encouragement to an address which to me seems big with the greatest mischiefs that can befall my country. You could not have found a person to whom your schemes were more disagreeable.”

Consider the reception Nicola’s letter might have received in other hands than Washington’s: “If you have any regard for your country, for posterity, or respect for me, banish these thoughts from your mind, and never communicate a sentiment of like nature.”

It happened again a year later. In March 1783, Washington refused to support the so-called “Newburgh Conspiracy,” a thinly veiled attempt by Continental officers to extort back pay from Congress by threatening a military coup.

Only one American could play the role of Caesar, and he twice refused to do it.

Two days before Christmas in 1783, Washington stood before Congress, the hall crowded with spectators, his hands visibly trembling. He spoke in a faltering voice. “Mr. President, having now finished the work assigned to me, I retire from the great theatre of Action; and bidding an Affectionate farewell to this August body under whose orders I have so long acted, I here offer my Commission, and take my leave of all the employments of public life.” He walked out, the hall ringing with applause.

Thomas Jefferson, present that day, understood the enormity of what he had witnessed: “The moderation and character of a single man has probably prevented the revolution from being closed, as most others have been, by a subversion of the liberty it was intended to establish.”

Had Washington possessed greater ambition and less character, the history of the United States would have been far different over the last two centuries.

After serving two terms as President, Washington walked away voluntarily again.

By surrendering power and refusing a dictatorship, Washington launched the American experiment on a firm foundation of principled and moral leadership that established that anyone who deviates from this model would be turning their back on one of the core values of the American republic—that ours is a government of laws, not of men—and one of the bedrock principles of American political leadership.

He secured to all mankind the gift of the world’s most enduring self-governing republic that, with all its flaws, remains an inspiration to the world.

The experiment continues, the outcome still in doubt. As Lincoln said, no one will ever conquer us—as a nation of free men and women, we shall live forever or die by suicide.

That need not be our destiny. When in doubt, look to our lodestar. As was said of Voltaire, so we can say about Washington: Consider that life and take courage.

Percy Shelley wrote that power poisons every hand that touches it. History is littered with the names of those who attained power ruthlessly, wielded it arbitrarily, and refused to give it up.

Percy Shelley wrote that power poisons every hand that touches it. History is littered with the names of those who attained power ruthlessly, wielded it arbitrarily, and refused to give it up.