“I carry you with me,

A ghost inside,

And in these shattered arms

You’re still alive.”

Heather Nova, “Walking Higher”

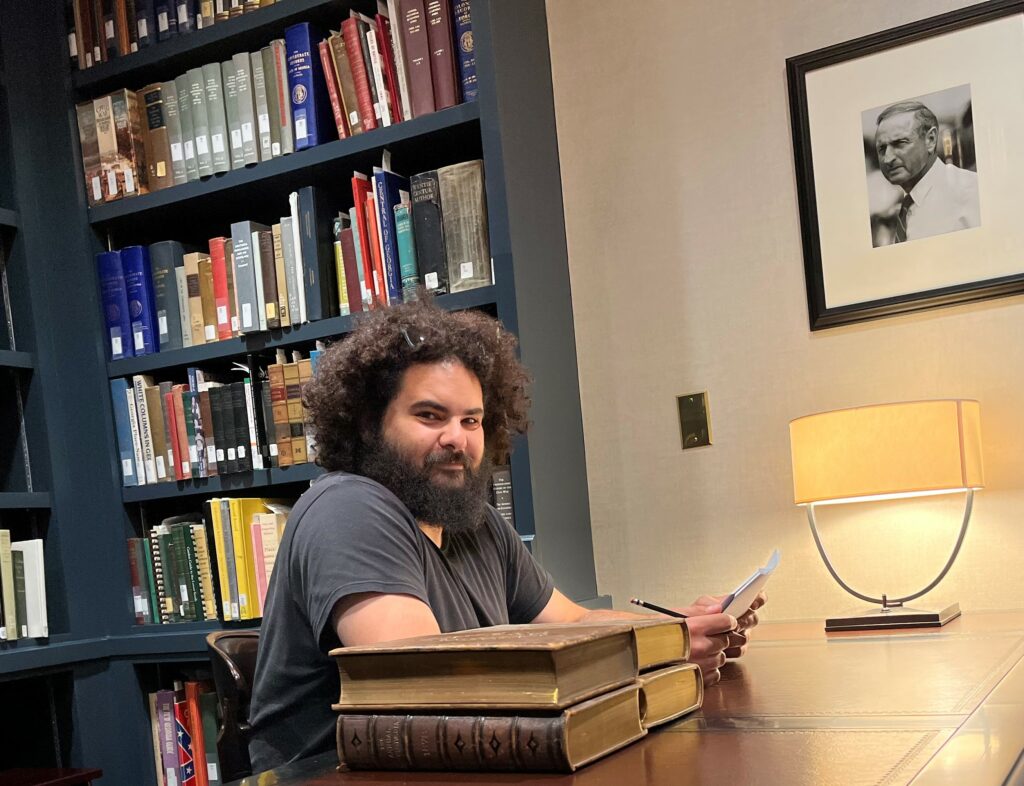

My father died one year ago, on September 5. A Sunday afternoon. 5:25 p.m. To say that I miss him doesn’t do justice to the wound that occupies the space he filled. I feel as if I’m drifting downstream, and I can still see him, standing on the riverbank. But I cannot swim back to him, against the current, and he can’t hear me calling for him. Every day, the waters that rush us along in life enlarge that gulf.

My father died one year ago, on September 5. A Sunday afternoon. 5:25 p.m. To say that I miss him doesn’t do justice to the wound that occupies the space he filled. I feel as if I’m drifting downstream, and I can still see him, standing on the riverbank. But I cannot swim back to him, against the current, and he can’t hear me calling for him. Every day, the waters that rush us along in life enlarge that gulf.

Some days I just want to call and talk to him about the latest Braves rookie phenom, or how good the Bulldogs look, or the best way to fix the belt on my lawn mower. I want him to know my knees hurt, just as his must have, when I painted the porch at our cabin this summer. Other days I want to hear his laughter, the way he laughed years ago when time and disease had not robbed him of the ability to let loose when something really tickled him.

Some days I just want to hear his voice say, “Hey Doc,” the way he always did whenever I called, and he picked up the phone. These are things I knew I would miss long before he was gone and knowing it has softened the blow not one whit.

Some days I just want to hear his voice say, “Hey Doc,” the way he always did whenever I called, and he picked up the phone. These are things I knew I would miss long before he was gone and knowing it has softened the blow not one whit.

Dad was a devoted Georgia Bulldogs and Atlanta Braves fan, and both teams won their respective championships in the months after his death. I know how much he would have loved to watch them win. I keep wanting to talk to him about it, to relive those glorious moments together, and it bothers me deeply that I can’t and never will.

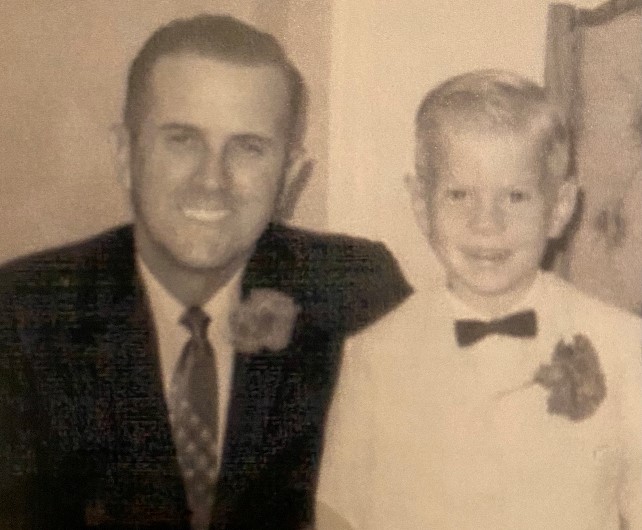

I want to tell him that I know now how hard it must have been for him when his own father died in 1979, when Dad was 46 years old, how sorry I am that I didn’t try harder to comfort him and be there for him. But I know that, even then, he expected no comfort from a 14-year-old boy. Still, I wish that I could have shared that pain with him in a more meaningful way, now that I fully comprehend how crushing that loss was.

I regret the things we never talked about, but the truth is, I asked him everything that I really wanted to know. Except one. In his last weeks, when he could no longer stand or walk, when he must have known the end was near, I wanted to ask him if he was afraid of dying. And I wanted to tell him how badly we would miss him when he was gone. But I couldn’t bring myself to do it. I didn’t want him to think there wasn’t hope, that we had given up, and so I remained silent.

I think I know what he would have said, though, given the example he lived throughout his long years. Afraid? No. It always seemed to me that Dad was incapable of fear. Death is part of life. I’m sure there were some days he welcomed it. But knowing him, I doubt he spent much time thinking about it. For Dad as for T.S. Eliot: “For us, there is only the trying. The rest is not our business.”

The last month was hard, but after reading about others who suffered from cancer or Alzheimer’s, there was much to be thankful for. His mind was clear up to the last 24 hours before his death. As he battled idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, we feared in his last moments he’d be gasping for breath. When the end came, however, it was as peaceful and easy as if he’d gotten up out of his chair and walked out of the room. Sometimes that’s what it seemed like. It still feels at times as if he’s just gone somewhere and will be coming back. The finality of it, the eternal-ness of it, knowing I won’t see him again if I live to be a hundred—that part has been hard to accept.

I remember walking into my parents’ bedroom shortly after his death, and there, peeking out from the dresser, was a pair of his shoes. It wasn’t as if I didn’t know about the power of things left behind, but I wasn’t prepared, in that moment, for those shoes. He would never wear them again. The reality of it seized me, strangled me, reduced me to a quivering mess. I fought through it then, as I’ve done many times since. Sometimes I can’t.

I remember walking into my parents’ bedroom shortly after his death, and there, peeking out from the dresser, was a pair of his shoes. It wasn’t as if I didn’t know about the power of things left behind, but I wasn’t prepared, in that moment, for those shoes. He would never wear them again. The reality of it seized me, strangled me, reduced me to a quivering mess. I fought through it then, as I’ve done many times since. Sometimes I can’t.

I have many of his things left behind. The hat he wore when he first began driving a truck professionally in 1959. His pocketknife. Many of his shirts, his smell living in them still. His belts. And his handkerchiefs. I tuck one in my pocket every day as I go off to work, just as he did. A tangible reminder in a small piece of fabric of a loss still deeply felt. I owe him everything.

Grief is ever constant, silent, unseen by those around you. Grief is navigated on muggy morning runs, on quiet walks, on Sunday evenings, watching a crimson sky fade to black. It sits with you in the silent watches of the night.

James Baldwin wrote that “after departure, only invisible things are left.” The world, he said, is held together “by invisible chains of memory, loss, and love.”

My aunt Corine turned 95 on Sunday, August 7. She is my father’s oldest sister, the last remaining child of nine born to my grandmother and grandfather, who were both born in the first years of the 20th century, 120 years ago. As a historian, I probably appreciate this kind of longevity in a different way than most people.

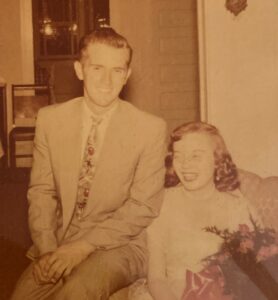

My aunt Corine turned 95 on Sunday, August 7. She is my father’s oldest sister, the last remaining child of nine born to my grandmother and grandfather, who were both born in the first years of the 20th century, 120 years ago. As a historian, I probably appreciate this kind of longevity in a different way than most people. Mother Teresa said that “In this life we cannot do great things. We can only do small things with great love.” Corine’s life has been a life of service and sacrifice. She was the oldest girl in a family of sharecroppers—six boys and three girls—with long years of hard toil in hot Georgia summers. (Dad used to jokingly tell listeners, “There were six of us boys in the family, and we each had three sisters.”) She revered her mother and father and lovingly helped to raise the seven siblings born after her. Indeed, she witnessed the entirety of those seven lives, literally from cradle to grave.

Mother Teresa said that “In this life we cannot do great things. We can only do small things with great love.” Corine’s life has been a life of service and sacrifice. She was the oldest girl in a family of sharecroppers—six boys and three girls—with long years of hard toil in hot Georgia summers. (Dad used to jokingly tell listeners, “There were six of us boys in the family, and we each had three sisters.”) She revered her mother and father and lovingly helped to raise the seven siblings born after her. Indeed, she witnessed the entirety of those seven lives, literally from cradle to grave. Corine (top right in the photo above) is now the last of Hubert and Reba’s nine children still alive, a singular fate that she neither understands nor welcomes but accepts without complaint. Age gains ground, little by little, and then in bursts. She is still in strong mind if faltering body, still living alone though lovingly cared for by two of my cousins, Susan and Kelly, who are surely angels on earth. She is a lone messenger from a long-distant and irretrievable past, the last living link to a vanished time and place, to the people who passed through those years with her, who laughed and prayed and sang and loved, now all left behind with tears and a promise to meet again.

Corine (top right in the photo above) is now the last of Hubert and Reba’s nine children still alive, a singular fate that she neither understands nor welcomes but accepts without complaint. Age gains ground, little by little, and then in bursts. She is still in strong mind if faltering body, still living alone though lovingly cared for by two of my cousins, Susan and Kelly, who are surely angels on earth. She is a lone messenger from a long-distant and irretrievable past, the last living link to a vanished time and place, to the people who passed through those years with her, who laughed and prayed and sang and loved, now all left behind with tears and a promise to meet again.