In this podcast Stan discusses the newly available Ed Jackson Collection at GHS, Freddie Mercury’s handwritten lyrics to “Bohemian Rhapsody,” Ed Ames’ tomahawk throw, and college students giving up their cellphones to take a vow of silence.

In this podcast Stan discusses the newly available Ed Jackson Collection at GHS, Freddie Mercury’s handwritten lyrics to “Bohemian Rhapsody,” Ed Ames’ tomahawk throw, and college students giving up their cellphones to take a vow of silence.

Do unexpected calls on your smart phone send you into panic mode? Should people text before calling? Do you hate text messages too? Is AI the end of the world as we know it? Stan discusses these pressing issues and more, including this year’s Pulitzer Prize winners, the travails of our beloved Braves, and the goings-on in the Fraternal Order of Tall People in Shorts.

President Joe Biden announced last week that he will seek a second term. For some, the power of the presidency is irresistible. Almost no one walks away voluntarily from seeking a second term. Lyndon Johnson was the last man who did in 1968, but only after Vietnam and domestic unrest combined to nearly destroy his presidency. And he was swept into office in one of the greatest landslides in history just four years earlier.

President Joe Biden announced last week that he will seek a second term. For some, the power of the presidency is irresistible. Almost no one walks away voluntarily from seeking a second term. Lyndon Johnson was the last man who did in 1968, but only after Vietnam and domestic unrest combined to nearly destroy his presidency. And he was swept into office in one of the greatest landslides in history just four years earlier.

Many presidents seek a second term to complete what they consider the unfinished business of the first term; in fact, the current incumbent used almost this exact language in announcing his bid for re-election. Only one president, James K. Polk, felt that he had completed everything he set out to accomplish when he stepped down willingly in 1849 after one term. His four years encompassed the annexation of Texas, the Mexican War, the dispute with Great Britain over the Oregon Territory, and the violent controversy over the westward expansion of slavery. The stress of it all contributed to Polk’s death at age 53, just three months after his term ended.

Historically, second terms are almost always disasters. From Washington to Barack Obama, almost every president who has served beyond four years came to grief on the rocky shoals of a second term. Political scandals, wars, assassinations, economic blunders, natural disasters, and foreign affairs (and sometimes domestic ones too, a la Bill Clinton) can quickly diminish popularity and political power, limiting a president’s leadership and ability to govern effectively.

Second-term woes go all the way back to our nation’s first president. George Washington agreed to seek a second term only after being persuaded to do so by Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson and Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton. Both men then promptly resigned and left Washington to preside over an increasingly divided country polarized by Jefferson’s Republicans and Hamilton’s Federalists.

Washington’s second term was bedeviled by diplomatic troubles with Great Britain—most notably the controversial Jay Treaty—and Revolutionary France. The day Washington left office he saw this vitriol directed at him in a Republican paper: “Would to God you had retired to private life four years ago. If ever a nation was debauched by a man, the American nation has been debauched by you.”

Thomas Jefferson’s first term was one of the most successful in American history—the Louisiana Purchase doubled the size of the country and hastened the Federalist party into extinction—and his popularity propelled him into a second term. But it was a disaster, again thanks to the diplomatic tangle of European affairs. Jefferson’s Embargo Act of 1807, which basically stopped American shipping abroad, nearly ruined the American economy and was enormously unpopular. Jefferson practically fled the White House in 1809.

Most other presidents who served two terms fared no better. The British army chased James Madison out of Washington before burning the city during the War of 1812. Andrew Jackson was censured by the Senate in his second term during the Bank War, the one and only time that has happened.

Lincoln was assassinated in his second term (as was McKinley), but had he lived his reputation might have foundered on the shoals of Reconstruction, just as Andrew Johnson’s did.

U.S. Grant was a war hero but the scandals of his second term marked his presidency as one of the worst in history.

World War I and the fight over the League of Nations nearly killed Woodrow Wilson in his second term. FDR’s ill-advised court-packing scheme during his second term nearly derailed his presidency and had World War II not been looming on the horizon, his political fortunes would have dropped considerably. Civil rights unrest, Sputnik, the Cold War, and Castro’s rise in Cuba all managed to douse Dwight Eisenhower’s popularity in the last years of his second term.

During the last 50 years, second terms have all been fraught with peril: the afore-mentioned LBJ (technically not a second term, but close, after finishing out JFK’s term); Nixon and Watergate; Reagan and the Iran-Contra affair; Clinton’s impeachment; while the Iraq war, the fumbled response to Katrina, and the economic meltdown eroded George W. Bush’s popularity to record-setting lows. And while Obama’s second term was not marked by outright scandal, it is not difficult to see Donald Trump’s 2016 election as a stinging rebuke to his administration.

Perhaps the Confederates got this part right: they limited their President to one six-year term, period. No worries about re-election, and the Congress knows it will have to deal with the same president for the next six years.

So why seek a second term at all? There is something about the power of the presidency, the pinnacle of political power, that is hard to give up voluntarily. Only time will tell if the current occupant succeeds where others have not. But history is not on his side.

As Thomas Jefferson said about the presidency from personal experience: “No man will ever bring out of that office the reputation which carries him into it.”

“Does anyone know where the love of God goes when the waves turn the minutes to hours?”

Gordon Lightfoot died on Monday, May 1, a transcendent singer and songwriter and one of the most talented and iconic musicians in the second half of the 20th century. I have loved his music from the moment I first heard him 50 years ago. His songs, like “Sundown,” “Carefree Highway,” “If You Could Read My Mind,” “Rainy Day People,” “Early Morning Rain,” “The Watchman’s Gone,” were all lyrical and deeply poetic, sung in that rich baritone voice, so easily imitable but impossible to replicate.

“The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald” was nothing less than an epic poem set to music and served as the unofficial soundtrack to that time of year “when the skies of November turn gloomy.” It rose to number 2 on the American Billboard charts, defying all norms of Top 40 standards with its length and arcane references to Lake Superior, Great Lakes shipping, and the legend that “lives on from the Chippewa on down.” I have listened to the song a thousand times, with its haunting guitar riffs and the mesmerizing story of the fateful ship that sank in the “face of a hurricane west wind” on November 10, 1975, on the “big lake they call Gitche Gumee.” Lightfoot, and many others, considered it his finest work.

He described himself as a songwriter in search of the “perfect poem” and to my mind, of all his compositions, “Song for a Winter’s Night” stands alone as a supreme achievement, a beautiful portrait of the aching loneliness of a dark night of longing:

The lamp is burnin’ low upon my tabletop

The snow is softly falling

The air is still in the silence of my room

I hear your voice softly calling

If I could only have you near

To breathe a sigh or two

I would be happy just to hold the hands I love

On this winter night with you.

(You should also check out this moving rendition by the Wichita State University School of Music.)

He was often hailed as a Canadian treasure—Geddy Lee, the lead singer of the Canadian rock band Rush, called him “our poet laureate,” while musician Tom Cochrane said that “if there was a Mount Rushmore in Canada, Gordon would be on it.”

But he really belonged to the world. As one critic noted, “It is impossible to explain the huge impact of Gordon Lightfoot on 20th century music. His songs were covered by everyone from Dylan to Elvis. His writing, imagery, and ability to create mood was without parallel.”

His songs were deceptively complex, layered with symbolism that belied the lyrics about mundane relationships, wandering spirits, or the beauty of the Canadian woodlands. “Don Quixote,” the heartbreaking “Bitter Green,” “The Watchman’s Gone,” and so many others, lent themselves to deeper meanings for anyone who cared to find them.

There’s a train down at the station

It’s come to carry my bones away

Two engines on

Twenty-one coaches long…

As I leave you in the sunset

Got one more nothin’ I’d like to say

‘You don’t know me

A son of the sea am I’

As I say to you, my brother

If you live to follow the golden sun

You better beware

Knowin’ the watchman’s always there.

If you find me feedin’ daisies

Please turn my face up to the sky

And leave me be

Watchin’ the moon roll by…

Drink Your Glasses Empty to this son of Orillia, Ontario, with the unmatched voice, who brought joy to so many with the gift of his song. Farewell and Godspeed, Gordon Lightfoot. We too have followed the golden sun.

The fire is dying

Now my lamp is growing dim

The shades of night are lifting

The morning light steals across my windowpane

Where webs of snow are drifting

If I could only have you near

To breathe a sigh or two

I would be happy just to hold the hands I love

On this winter night with you

And to be once again with you.

Item: Play Ball: It’s April, and Major League Baseball has returned, complete with a pitch clock, larger bases, and other rule changes designed either to speed up the game or otherwise make it more exciting for the casual fan. So far our beloved Braves are off to a very hot start and look better than the hated Mets or Phillies (the reigning National League champions who finished a distant 3rd place in the NL East)—and better than the version that won the 2021 World Series. Time will tell, but this should be a fun season.

Item: Hoops: In the meantime, I hope you didn’t miss the Women’s Final Four in college basketball or the championship game between LSU and Iowa, instant classics all. Angel Reese, Georgia Amoore, Aliyah Boston, and Caitlin Clark, are all superstars right now, with many years and great games ahead of them in the WNBA–whose season starts May 19 by the way, with 40 games on the schedule this year. Our Atlanta Dream opens the season on Saturday, May 20, at the Dallas Wings, 1pm on ABC. Don’t miss it.

Item: More Hoops/Football: Speaking of college basketball, just one observation—uninhibited by the thought process—about the men’s final, featuring the exciting San Diego State Aztecs. Their run to the final was great fun to watch and they’re an explosive team. But they were a 5th seed and I kept wondering, if they win the championship, can we really believe that they were the best team in all of college basketball through the year—or just the best team over a number of weeks, during the tournament? Doesn’t matter, right, if they win the championship game? Except that I kept thinking that the college football playoffs are about the expand to 12 teams, and it’s inevitable that a low seed with 3 losses during the regular season will get hot for a few weeks and win it all by beating a previously unbeaten team. Will they really be the champions? Or just a hot team at the right time? Yes to both. I get that it’s much more unlikely in college football that a team with three losses will upset an undefeated team on a neutral field, but it’s bound to happen eventually—like a 16th-seed beating a 1-seed in basketball: it’s only happened twice, but it has happened. It will happen in college football too, and it will dilute the sport, no doubt about it. But it’s inevitable. Then again, my team has won back-to-back championships under the current system, so I’m prejudiced. Moving on…

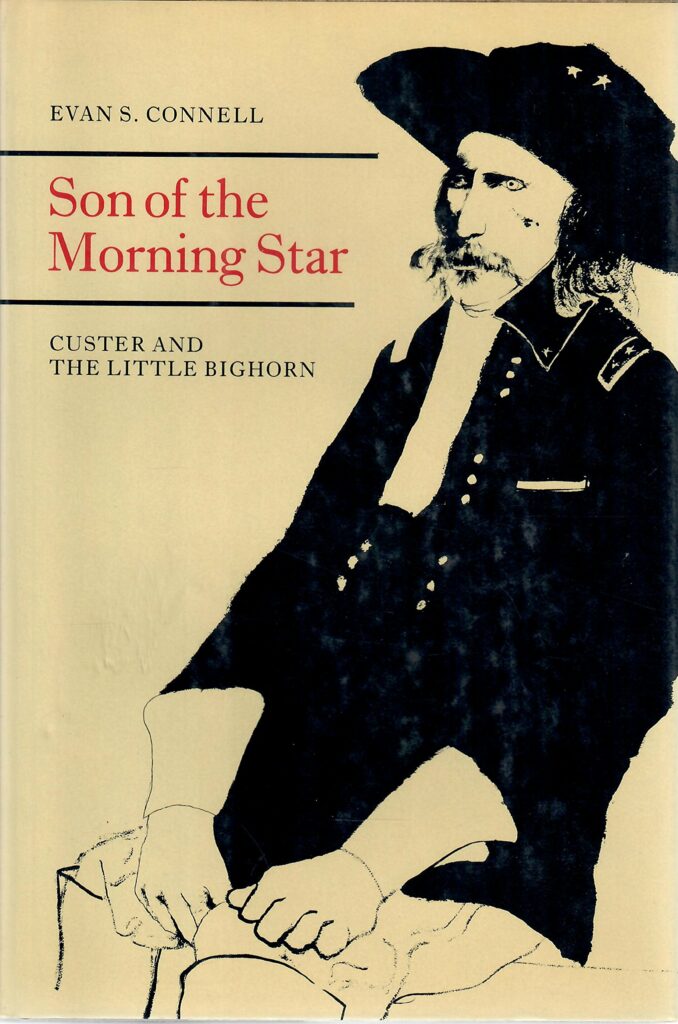

Item: Books, or A Case of Serendipity: I recently bought a copy of T.J. Stiles’s 2015 book, Custer’s Trials: A Life on the Frontier of a New America, which won the 2016 Pulitzer Prize for History. As I was putting it on the appropriate shelf in my office, I noticed immediately beside it my copy of Evan Connell’s 1984 best-seller on Custer, Son of the Morning Star, which has been hailed as a masterpiece. I remember buying the book as an undergraduate at UGA just getting interested in history. Why had I never read it? And who was Evan Connell? I remember reading articles in the mainstream media (like Time magazine) about how this unusual book and author surprisingly took the literary world by storm that year. I did the usual Google searches on Connell and found myself fascinated by what I discovered. Suffice it to say, Connell is considered a writer’s writer, at home in nearly every genre, from fiction, essays, and short stories, to history, biography, and poetry. The contemporary of Jack Kerouac, Philip Roth, and John Updike labored in comparatively undeserved obscurity, but hiding in plain sight was part of his deliberate brand. Connell, who died in 2013 at age 88, was a lifelong unmarried loner, the opposite of a self-promoter, who hated publicity and never courted the spotlight. He granted few interviews (none on camera) and if there’s a picture out there anywhere of him smiling, I’ve never seen it. He never did public readings of his work, never spoke publicly about his writing, never taught classes about writing or literature. He lived in the Bay Area much of adult life, spent some time in local watering holes, and formed few permanent attachments. He

Item: Books, or A Case of Serendipity: I recently bought a copy of T.J. Stiles’s 2015 book, Custer’s Trials: A Life on the Frontier of a New America, which won the 2016 Pulitzer Prize for History. As I was putting it on the appropriate shelf in my office, I noticed immediately beside it my copy of Evan Connell’s 1984 best-seller on Custer, Son of the Morning Star, which has been hailed as a masterpiece. I remember buying the book as an undergraduate at UGA just getting interested in history. Why had I never read it? And who was Evan Connell? I remember reading articles in the mainstream media (like Time magazine) about how this unusual book and author surprisingly took the literary world by storm that year. I did the usual Google searches on Connell and found myself fascinated by what I discovered. Suffice it to say, Connell is considered a writer’s writer, at home in nearly every genre, from fiction, essays, and short stories, to history, biography, and poetry. The contemporary of Jack Kerouac, Philip Roth, and John Updike labored in comparatively undeserved obscurity, but hiding in plain sight was part of his deliberate brand. Connell, who died in 2013 at age 88, was a lifelong unmarried loner, the opposite of a self-promoter, who hated publicity and never courted the spotlight. He granted few interviews (none on camera) and if there’s a picture out there anywhere of him smiling, I’ve never seen it. He never did public readings of his work, never spoke publicly about his writing, never taught classes about writing or literature. He lived in the Bay Area much of adult life, spent some time in local watering holes, and formed few permanent attachments. He  died alone in Santa Fe, New Mexico. And yet his novels reveal a remarkably penetrating insight into human relationships that are astonishing for someone who seemed to spend most of his life shunning them. His 1959 novel Mrs. Bridge (a National Book Award finalist) was praised as a masterpiece of spare, lean, concise story-telling, with not a spare word in it, as was his 1969 follow-up, Mr. Bridge. I bought and devoured them both and wished for more. I finally also read Son of the Morning Star (published by then-little-known North Point Press in Berkeley, now owned by FSG) and found it beautifully written and moving as well. The New York Times called it “impressive in its massive presentation of information” and added that “its prose is elegant, its tone the voice of dry wit, its meandering narrative skillfully crafted.” The Washington Post said it “leaves the reader astonished,” and the Wall Street Journal called it “a scintillating book, thoroughly researched and brilliantly constructed.” I can confirm that all of this is true. Happily, for people like me who are fascinated by him, there’s a new literary biography of Connell out by Steve Paul, Literary Alchemist: The Writing Life of Evan S. Connell, published in 2021 by the University of Missouri Press. And so, through the serendipity of shelving one book, Evan Connell is now on my list as a favored author whose writings I plan to work through patiently and in their entirety, one bite at a time. I’ll be spending considerable time with him in the coming years. If you love the power of words, I invite you also to get to know this talented, mysterious man in the only way we can—through his writing.

died alone in Santa Fe, New Mexico. And yet his novels reveal a remarkably penetrating insight into human relationships that are astonishing for someone who seemed to spend most of his life shunning them. His 1959 novel Mrs. Bridge (a National Book Award finalist) was praised as a masterpiece of spare, lean, concise story-telling, with not a spare word in it, as was his 1969 follow-up, Mr. Bridge. I bought and devoured them both and wished for more. I finally also read Son of the Morning Star (published by then-little-known North Point Press in Berkeley, now owned by FSG) and found it beautifully written and moving as well. The New York Times called it “impressive in its massive presentation of information” and added that “its prose is elegant, its tone the voice of dry wit, its meandering narrative skillfully crafted.” The Washington Post said it “leaves the reader astonished,” and the Wall Street Journal called it “a scintillating book, thoroughly researched and brilliantly constructed.” I can confirm that all of this is true. Happily, for people like me who are fascinated by him, there’s a new literary biography of Connell out by Steve Paul, Literary Alchemist: The Writing Life of Evan S. Connell, published in 2021 by the University of Missouri Press. And so, through the serendipity of shelving one book, Evan Connell is now on my list as a favored author whose writings I plan to work through patiently and in their entirety, one bite at a time. I’ll be spending considerable time with him in the coming years. If you love the power of words, I invite you also to get to know this talented, mysterious man in the only way we can—through his writing.

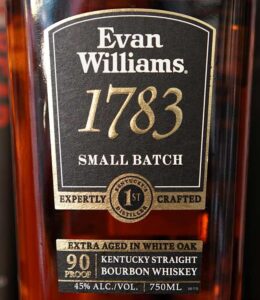

Item: Bourbon: Speaking of Evan, Evan Williams has long been known among bourbon lovers as one of the best low-priced (read “cheap”) bourbons on the market. This is especially true of Evan Williams 1783 Small Batch, which I highly recommend. The date comes from the year that Williams founded Kentucky’s first distillery. If you’re keeping score, this particular batch is 78 percent corn, 12 percent malted barley, and 10 percent rye. For those uninitiated, enjoying bourbon whiskey is quite simple: pour it into the appropriate glass, either over a few cubes of ice or without, then a) see the bourbon, b) smell the bourbon, and c) taste the bourbon. This one is aged 6-8 years, so you will see a nice copper bronze in your glass. You will smell charred oak, caramel, and vanilla. You will taste all three plus brown sugar and a flash of heat as it goes down. Nicely priced and packaged, widely available, and back up to 90 proof (previously 86), this is a great entry-level bourbon that I highly recommend for the upcoming Kentucky Derby Day—or any upcoming day, actually. As always, I am not getting paid to endorse this product, but I should be.

Item: This week in Literary History: On April 3, 1783, 240 years ago, Washington Irving (not to be confused with famous cricketer Irving Washington), another of my favorite authors, was born in New York City, the youngest of 11 children. He will become the first American author to gain critical and popular fame in this country and in Europe. Charles Dickens, another favorite, said of him: “I don’t go upstairs to bed two nights out of seven without taking Washington Irving under my arm.” On April 6, 1895, author Oscar Wilde is on trial in London for sodomy and gross indecency. He was accused on the stand of having written the story, “The Priest and the Acolyte,” a story of a love affair between an Anglican priest and a 14-year old boy (it was actually written by John Francis Bloxam). Wilde denied authorship and when asked if the story was immoral, he famously replied, “It was much worse than immoral. It was badly written.”

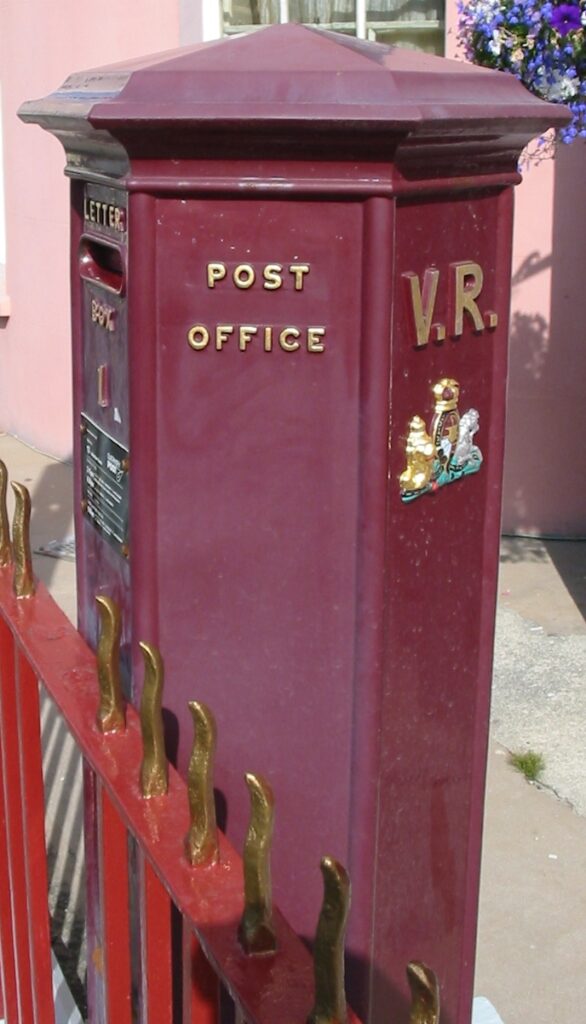

Item: Currently Reading: The Last Chronicle of Barset, by Anthony Trollope (originally published in 1867), the final volume (of 6) in the Barsetshire series that begins with The Warden (1855) then continues with Barchester Towers (1857), Doctor Thorne (1858), Framley Parsonage (1861), and The Small House at Allington (1864), chronicling the always interesting goings-on in the fictional county of Barsetshire and its cathedral town of Barchester during the height of the Victorian Era. The county is peopled with delightful almost-living characters like The Rev. Mr. Quiverful, Mrs. Proudie, Sir Omicron Pie, Dr. Fillgrave, Sir Abraham Haphazard, Sir Raffle Buffle, and many, many others. The series is beloved by Trollope fans, who are legion, ranging from actor Alex Guinness (Obi-Wan Kenobi), who never travelled without a Trollope novel, to economist John Kenneth Galbraith, to author Sue Grafton. It’s taken me 14 years to read the series, not because the books are hard to read—just the opposite; one critic said they’re like eating peanuts, hard to stop—but because I let too many years elapse between volumes. After this, it’s on to Trollope’s 6-volume Palliser series, which I hope to finish in half the time. Maybe I’ll read those straight through? At any rate, Trollope is also one of my favorite authors, not only for his wonderful books but because of how he wrote them. He famously kept to a disciplined schedule, putting in 3 hours at his writing desk every day before going to his real job at the Post Office, where he is credited with introducing the ubiquitous red pillar mailbox to the United Kingdom (seen here). His literary output was prodigious by any standards: 47 novels, 42 short stories, 5 travel books, 2 works of non-fiction, and an auto-biography. I intend to read them all.

Item: Currently Reading: The Last Chronicle of Barset, by Anthony Trollope (originally published in 1867), the final volume (of 6) in the Barsetshire series that begins with The Warden (1855) then continues with Barchester Towers (1857), Doctor Thorne (1858), Framley Parsonage (1861), and The Small House at Allington (1864), chronicling the always interesting goings-on in the fictional county of Barsetshire and its cathedral town of Barchester during the height of the Victorian Era. The county is peopled with delightful almost-living characters like The Rev. Mr. Quiverful, Mrs. Proudie, Sir Omicron Pie, Dr. Fillgrave, Sir Abraham Haphazard, Sir Raffle Buffle, and many, many others. The series is beloved by Trollope fans, who are legion, ranging from actor Alex Guinness (Obi-Wan Kenobi), who never travelled without a Trollope novel, to economist John Kenneth Galbraith, to author Sue Grafton. It’s taken me 14 years to read the series, not because the books are hard to read—just the opposite; one critic said they’re like eating peanuts, hard to stop—but because I let too many years elapse between volumes. After this, it’s on to Trollope’s 6-volume Palliser series, which I hope to finish in half the time. Maybe I’ll read those straight through? At any rate, Trollope is also one of my favorite authors, not only for his wonderful books but because of how he wrote them. He famously kept to a disciplined schedule, putting in 3 hours at his writing desk every day before going to his real job at the Post Office, where he is credited with introducing the ubiquitous red pillar mailbox to the United Kingdom (seen here). His literary output was prodigious by any standards: 47 novels, 42 short stories, 5 travel books, 2 works of non-fiction, and an auto-biography. I intend to read them all.

Item: Finally, this little gem from columnist Giles Coren of The Times of London: “I’ve always thought of art as culture for people too thick to read books. The super-rich invariably collect paintings but I’ve never met one who could quote Milton.”—Coren, in The Times of London, February 27, 2023. Ouch.

Until next time, thanks for reading.