Stan’s guest this week is Jerry Grillo, author of Big Cat: The Life of Baseball Hall of Famer Johnny Mize. Mize was born in Demorest, Georgia, and played 15 seasons in Major League Baseball and won 5 World Series.

Stan’s guest this week is Jerry Grillo, author of Big Cat: The Life of Baseball Hall of Famer Johnny Mize. Mize was born in Demorest, Georgia, and played 15 seasons in Major League Baseball and won 5 World Series.

This first appeared as an editorial in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution on Monday, February 19, 2024.

Percy Shelley wrote that power poisons every hand that touches it. History is littered with the names of those who attained power ruthlessly, wielded it arbitrarily, and refused to give it up.

Percy Shelley wrote that power poisons every hand that touches it. History is littered with the names of those who attained power ruthlessly, wielded it arbitrarily, and refused to give it up.

In one of history’s most famous stories, King George III asked the American painter Benjamin West what George Washington would do after winning independence. West replied, “They say he will return to his farm.” King George was incredulous: “If he does that, he will be the greatest man in the world.”

At the end of the American Revolution, George Washington rode to Annapolis, Maryland, where Congress was in session, to resign the commission he had accepted in June 1775, eight years earlier.

Consider what he was doing. Congress had vested full military authority in Washington to lead the Continental Army as commander in chief, and he had done so for the duration of the conflict. At least twice toward the end of that period, however, he was encouraged by others to seize power as dictator.

The Confederation Congress was weak and had virtually no ability to raise revenue to pay its expenses, chief among them the back pay of soldiers and officers of the Continental Army, months in arrears. Now was the time for Washington to strike.

On May 22, 1782, Washington received a letter from Colonel Lewis Nicola of Pennsylvania, proposing that Washington seize power with the help of the army and declare himself dictator or king. It had apparently been talked about for some time. Nicola was proposing nothing less than a military coup.

Revolutions often dissolve into dictatorships. Chaos breeds the conditions for a strong man to seize power, claiming to have all the answers and authority to solve complex problems. For many people this was where the road of self-government always ended. Why should the American Revolution have been any different?

If there was ever a moment in American history when one individual could have felt justified in seizing power and doing the unthinkable, that was it. There was no central government, no executive branch, no federal bureaucracy, no Supreme Court, and he was head of the national army. Washington could not be charged with acting unconstitutionally because there was no Constitution. Rule of law? Washington could have been the law.

No. Washington responded to Nicola with scorn and contempt. “Be assured, Sir, no occurrence in the course of the war has given me more painful sensations than such ideas existing in the Army as you have expressed, and I view them with abhorrence and reprehend with severity. I am at a loss to conceive what part of my conduct could have given encouragement to an address which to me seems big with the greatest mischiefs that can befall my country. You could not have found a person to whom your schemes were more disagreeable.”

Consider the reception Nicola’s letter might have received in other hands than Washington’s: “If you have any regard for your country, for posterity, or respect for me, banish these thoughts from your mind, and never communicate a sentiment of like nature.”

It happened again a year later. In March 1783, Washington refused to support the so-called “Newburgh Conspiracy,” a thinly veiled attempt by Continental officers to extort back pay from Congress by threatening a military coup.

Only one American could play the role of Caesar, and he twice refused to do it.

Two days before Christmas in 1783, Washington stood before Congress, the hall crowded with spectators, his hands visibly trembling. He spoke in a faltering voice. “Mr. President, having now finished the work assigned to me, I retire from the great theatre of Action; and bidding an Affectionate farewell to this August body under whose orders I have so long acted, I here offer my Commission, and take my leave of all the employments of public life.” He walked out, the hall ringing with applause.

Thomas Jefferson, present that day, understood the enormity of what he had witnessed: “The moderation and character of a single man has probably prevented the revolution from being closed, as most others have been, by a subversion of the liberty it was intended to establish.”

Had Washington possessed greater ambition and less character, the history of the United States would have been far different over the last two centuries.

After serving two terms as President, Washington walked away voluntarily again.

By surrendering power and refusing a dictatorship, Washington launched the American experiment on a firm foundation of principled and moral leadership that established that anyone who deviates from this model would be turning their back on one of the core values of the American republic—that ours is a government of laws, not of men—and one of the bedrock principles of American political leadership.

He secured to all mankind the gift of the world’s most enduring self-governing republic that, with all its flaws, remains an inspiration to the world.

The experiment continues, the outcome still in doubt. As Lincoln said, no one will ever conquer us—as a nation of free men and women, we shall live forever or die by suicide.

That need not be our destiny. When in doubt, look to our lodestar. As was said of Voltaire, so we can say about Washington: Consider that life and take courage.

This week Stan’s guest is historian and author Elizabeth Varon from the University of Virginia discussing her latest book, Longstreet: The Confederate General Who Defied The South. She talks about the life and career of this most controversial Georgian, from whether “Longstreet was late” at Gettysburg, and how his post-war decision to support Radical Reconstruction, Black office-holding and voting, and his post-war criticisms of Robert E. Lee all combined to nearly destroy his reputation and his life.

A shorter version of this essay first appeared in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution on Wednesday, January 3, 2024, and can be seen here.

Many people are asking, can a candidate run for the presidency from prison? Yes, and it’s happened before—to a Socialist who received nearly a million votes.

Eugene Debs ran as the Socialist Party nominee for president five times in the six presidential elections between 1900 and 1920—and in 1920 he ran from the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary.

Debs was born in Terre Haute, Indiana, in 1855. He left home at age fourteen to work on the railroad and became involved in the nascent efforts to organize labor unions. Before his 20th birthday he helped create a local lodge of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen, rising to become a national officer within five years. By the time he was 30 he was serving in the Indiana legislature.

Debs was a labor organizer, but he was not anarchist. He had been shocked by Chicago’s Haymarket Riots of 1886. Though he was the son of Alsatian immigrants, he still indulged in nativist rhetoric, insisting that the incoming tide of Eastern European Jews and Southern European Catholics in the late 19th century threatened Protestant White Americans. “The Dago,” he said, “works for small pay and lives far more like a savage or a wild beast than the Chinese.” Like a modern-day cable news talking head, he warned that “Italy has millions to spare, and they are coming.” He denounced the influx of Russian Jews as “criminals and paupers.”

By the 1890s, the growing power of corporations and the threat they posed to workers led Debs to oppose all attempts to divide workers against themselves based on ethnicity. Class, not religion, was his fault line. He led the American Railway Union in a successful strike for higher wages against the Great Northern Railway in April 1894.

Debs gained greater renown—and vilification—in 1895 when he was sentenced to six months in jail for his role in leading the Chicago Pullman Palace Car Company strike, which severely disrupted rail traffic in the Midwest during the summer of 1894. That strike was historic: it marked the first time that the Federal government resorted to an injunction to break the strike.

Sitting in jail for his 40th birthday, Debs read Karl Marx’s Das Kapital, and though he never embraced Marxian Socialism, he grew to loathe competitive capitalism. Lincoln, not Lenin, remained his hero. But the rail-splitter’s America was gone, replaced by an economic system that Debs felt would have been unrecognizable to the Founders.

Debs emerged from jail more defiant than ever. An inspiring speaker, he energized a crowd of more than 100,000 in Chicago, denouncing capitalism and advocating for “the Spirit of ’76” and a system that allowed every worker “the opportunity to advance to the fullest limits of his abilities.” He was not a revolutionary, calling instead for workers to seize power through the ballot and reclaim the country that was rightfully theirs.

In 1897 he proclaimed himself a Socialist and founded the Socialist Party of America, injecting European-style class conflict into American politics.

Debs ran for president at the head of his party in 1900, receiving 96,000 votes; the total grew to 400,00 four years later. He ran again in 1908 and 1912, receiving 6 percent of the vote.

With the U.S. entry into World War I, the Federal government’s need for increased industrial production clashed headlong with the goals of Debs and organized labor. In the flurry of war-time patriotism, Congress passed the Espionage Act of 1917, designed to punish acts deemed disloyal, dangerous, and disruptive of the war effort. “I believe in free speech, in war as well as in peace,” Debs declared. “If the Espionage Law stands, then the Constitution of the United States is dead.” Flouting the law, Debs encouraged young American men not to fight: “The master class has always declared the wars, the subject class has always fought the battles.”

Federal authorities pounced. Prosecutor Edwin Wertz announced that “No man, even though four times the candidate of his party for the highest office, can violate the basic law of this land.” Debs was charged with violating the Espionage Act and convicted of sedition in 1918—and disfranchised for life. He was sentenced to three concurrent ten-year sentences. (Ironically, the same Act was used to charge Donald Trump in his handling of classified documents.)

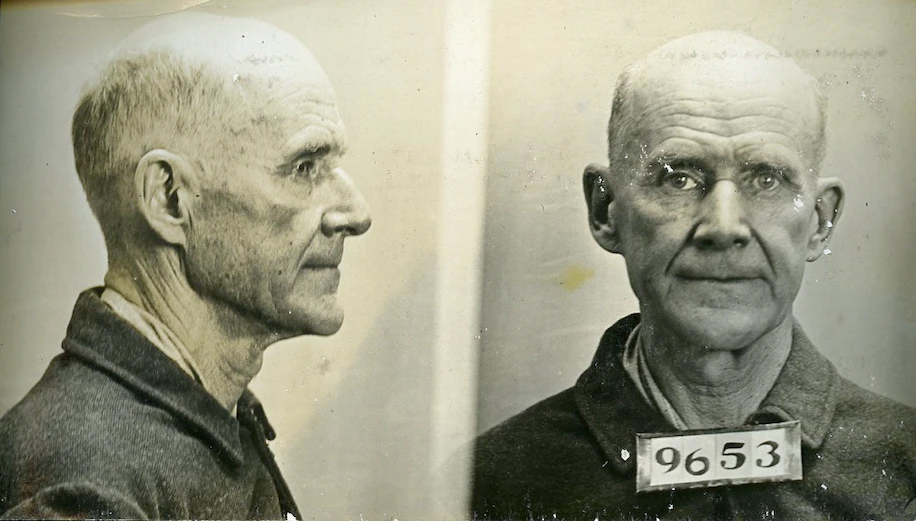

Whether First Amendment martyr or war-time traitor, Eugene Debs found himself running as the Socialist candidate for president in 1920 from the Atlanta Federal prison. He told his supporters, who handed out photos of the candidate in convict denim, along with campaign buttons for “Prisoner 9653,” “I enter the prison doors a flaming revolutionist, my head erect, my spirit untamed and my soul unconquerable.” Despite the obvious impediments to his campaign and doubts about his eligibility, Debs received 915,000 votes for president—3.5 percent—the highest total the party ever won.

President Warren Harding finally released Debs—but did not pardon him—on Christmas Day 1921, and promptly invited him to the White House, where Debs’s charm was on full display. Fifty thousand supporters greeted him on his return to Indiana. But it was a pyrrhic victory, as prison nearly broke him. His health was ruined.

Debs died five years later, in 1926, at age 70, his dream and his cause in ruins. To this point, Eugene Debs remains the only presidential candidate to seek the office while imprisoned after a Federal conviction.

Stan’s guest this week is best-selling author Jeryn Turner, who discusses her writing life, her upbringing, books, and the inspiration behind her fulfilling life.