Earlier this week, my colleague Lisa “War Eagle” Landers, the GHS Education Coordinator, sent me a letter she had received from a middle school teacher, who asked:

“Do you know why Lester Maddox, once elected governor, chose to appoint so many African Americans to government positions given his strong record on segregation? It would seem he would favor an all-White government. I have done a lot of research on Lester Maddox trying to find that information with no luck. I have to think it was for self-gain.”

It’s a great question. Lisa asked me for a response, and I thought I’d knock out a quick reply. The answer turned out to be a bit more complicated than I thought.

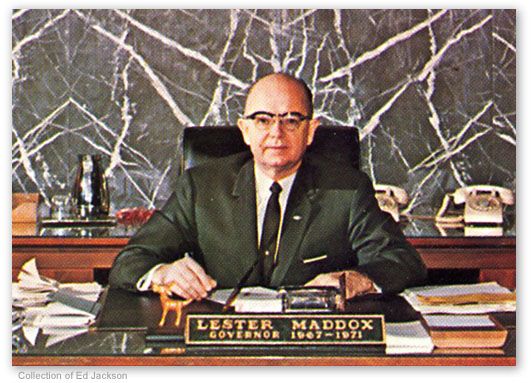

It was one of the great ironies in Georgia history: Maddox had run for governor in 1966 on a segregationist, states-rights platform—despite & because of the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965—but then once in power he appointed more Black Georgians to positions in state government than any previous governor. He also desegregated the Georgia State Patrol, no small thing all by itself.

Every available source on Governor Maddox tells us these facts, but as I prepared my response for Lisa, I realized that the usual go-to sources don’t directly answer the question as to why. What was Maddox’s motivation?

Lester Maddox was the original Donald Trump. He campaigned as an outsider who loathed the establishment. He was a businessman with no political experience. He behaved in diametrically opposite ways from more button-downed establishment politicians. He hated the press but loved publicity. He made deliberately provocative statements to rev up his base. He labeled political opponents as not just wrong but as un-American socialists and communists. And no one gave him a chance of actually becoming governor.

As UGA history professor Numan Bartley explained in a 1974 Georgia Historical Quarterly article: “Sophisticated observers found it difficult to take Maddox seriously, given his reputation for antics and colorful fanaticism, but, like Eugene Talmadge before him, Maddox had a genuine appeal for the white common folks.”

Sound familiar?

Maddox, unlike Trump, came from very modest circumstances. He quit high school during the Great Depression to help support his family. As an outspoken segregationist, he had twice run unsuccessfully for mayor of Atlanta and Lt. Governor of Georgia. But Maddox had made a name for himself as the owner of The Pickrick cafeteria near Georgia Tech, where he steadfastly refused to serve Black customers, even after the passage of national Civil Rights laws that required him to do so. In July 1964 he even chased several Black Tech students out of his business with an ax handle, which soon became one of his popular public props. Maddox eventually sold his restaurant rather than integrate.

All of this, of course, made Maddox wildly popular with the many White Georgians who fiercely opposed the Civil Rights movement. When he ran for governor in the 1966 Democratic primary against the much more moderate Ellis Arnall, Maddox, according to Bartley, “projected a certain charisma with his earnest blend of social segregation and religious fundamentalism.”

Maddox held nothing back. In the words of the New York Times, Maddox’s openly racist platform “included the view that blacks were intellectually inferior to whites, that integration was a Communist plot, that segregation was somewhere justified in Scripture and that a federal mandate to integrate schools was ‘ungodly, un-Christian and un-American.’” The Ku Klux Klan wholeheartedly endorsed him.

Less than two years after the passage of two of the most far-reaching pieces of social legislation in American history, angry and resentful White Georgians were in no mood for moderation. Maddox won 64 percent of the rural vote, but only 41 percent of the urban, much as Trump would 50 years later. And like Trump, Maddox overwhelmingly won White working-class voters (70 percent in urban areas) but only about a quarter of more affluent Whites, and only 0.3 percent of the urban Black vote. In the general election, Republican Bo Callaway outpolled Maddox but didn’t gain a majority, throwing the contest into the Democratic-controlled House, where the ax-handle-wielding Maddox won easily.

As with the presidential election 50 years later, the establishment across the nation staggered in disbelief that the man pilloried as an outspoken clown had triumphed. Time magazine labeled him a “strident racist.” Newsweek dismissed him as a “backwoods demagogue out in the boondocks.” Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., said Maddox’s election made him ashamed to be a Georgian. Two years later, Governor Maddox refused to honor the martyred King by allowing his body to lie in state in Georgia’s Capitol, nor did he attend his funeral or lower state flags to half-mast.

Georgians and national observers braced for the publicity-seeking Maddox to roll back the clock and begin an all-out war of Massive Resistance to Civil Rights. But that didn’t happen.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia summarizes Maddox’s accomplishments thus: “Maddox proved reasonably progressive on many racial matters. As governor he backed significant prison reform, an issue popular with many of the state’s African Americans. He appointed more African Americans to government positions than all previous Georgia governors combined, including the first Black officer in the Georgia State Patrol and the first Black official to the state Board of Corrections. Though he never finished high school, Maddox greatly increased funding for the University System of Georgia.”

How to explain the enigma of Lester Maddox?

The traditional sources list these facts but offer little else. To gain more insight, I called two of Georgia’s most knowledgeable political insiders: Jim Galloway, a 40-year veteran of the Atlanta Journal-Constitution and the former lead writer and founder of the AJC’s Political Insider blog; and Keith Mason, Governor Zell Miller’s chief of staff.

They both readily agreed that whatever else Lester Maddox was, he was an astute politician with good instincts who hired highly qualified and capable people to fill administrative posts. The best of these was undoubtedly a teacher from north Georgia named Zell Miller, hired in 1969 to serve as Governor Maddox’s executive secretary, as the Chief of Staff position was known at that time.

It was Miller who pushed Maddox toward progressive policies regarding race and higher education, and Maddox was smart enough to listen. Galloway also suggested that however racist Maddox may have been at heart, he did not want to be remembered as a leader who took Georgia backward. Instead, looking toward a political future beyond the governorship, Maddox worked hard to build an image that was at odds with everything he had done to win the office. He was savvy enough to know that, though he may not like it, Black voters would play a prominent role in Georgia’s future, and he wanted to be able to point to substantive racial accomplishments during his administration. It turns out that even the brazenly outspoken Lester Maddox didn’t want to be remembered as nothing more than a bigot.

But that was Maddox the politician. Maddox the man changed very little. He endorsed George Wallace for president in 1968, called MLK an “enemy of our country” after his assassination, and ran for president himself in 1976 against Jimmy Carter (who Maddox called the most corrupt man he’d ever met). Though he never changed, Georgia did: voters rejected Maddox’s repeated attempts to regain Georgia’s governorship.

Till the end Lester Maddox denied to all who would listen that he was not and had never been racist in his life. Jim Galloway said that in every conversation he had with him, Maddox pushed back hard against any notion that there was anything to atone for. Still, he remained unapologetically committed to segregation till the day he died on June 25, 2003: “I want my race preserved, and I hope most everybody else wants theirs preserved. I think forced segregation is illegal and wrong. I think forced racial integration is illegal and wrong. I believe both of them to be unconstitutional.”

In 1999, the State of Georgia dedicated the Lester and Virginia Maddox Bridge, located on Interstate 75 in Cobb County, near Truist Park. Not surprisingly, the name has come under fire in the last year in the wake of the movement to remove controversial statues and names of White supremacists from public landmarks.

Who was Lester Maddox? Was he the man with the ax-handle who chased Black patrons from his restaurant? Or the man who broke the color barrier at the Georgia State Patrol and insisted that police officers address Black Georgians with respect?

Zell Miller, himself no stranger to charges of political inconsistency, believed that, “No man in Georgia public life has been more maligned, more misrepresented, or more misunderstood than Lester Maddox.”

Georgia is once again in the national spotlight: For the first time in its history, Georgia recently elected a Black man and a Jewish man to represent the state in the US Senate. Georgia also recently passed a controversial voting law that its advocates say promotes election integrity but has brought national scrutiny amid charges that the law aims to suppress minority votes.

Modern Georgia, like the legacy of Lester Maddox—indeed, like all of our history—is more complicated than we think.