When news outlets first reported the Colonial Pipeline software cyberattack last weekend, they warned that if the pipeline didn’t come back online in the near future, gas prices would in all likelihood be rising.

From that news, it took virtually no time for people to assume that must mean that there was no gasoline now, nor would there ever be again. Gasoline as we had known it was gone, never to return. Therefore, we should all go out and fill up our cars at the same time—RIGHT NOW!!!!—whether you had any gas in your car or not. Maybe you filled your car up just yesterday, or maybe you wouldn’t need gas for another week. No matter! Go now and top it off! Wait hours if you must, but go get gas now, now, now!!!

We thus ensured that we turned a mild inconvenience—higher gas prices—into a full-blown disaster.

You may recall that at this same time last year, during the pandemic, people rushed out to buy toilet paper in mass quantities—not because there wasn’t any, but because social media rumors spread that toilet paper might become scarce. So the obvious thing to do was to run out and panic buy as much as you could, RIGHT NOW!!

People got into fistfights over toilet paper. Viral videos of check-out-line shaming lit up the internet, as people bought 198 rolls at once. People who couldn’t find toilet paper were afraid to eat Varsity chili dogs. Other unfortunates began ordering bidets. Panic ensued.

What is it about the human condition that makes us act this way? And if you think this is a recent phenomenon or needs social media to happen, watch the classic “Twilight Zone” episode, “The Monsters are Due on Maple Street,” first broadcast in 1960.

I’m working in metro Atlanta this week, and people are lined up to buy gasoline. Those of us who are old enough to remember the gas crisis lines of the 1970s found it eerily familiar.

As a historian, I started thinking about a time in this country when gasoline was actually rationed and wondered, what would we do if that happened again?

With America’s entry into World War II in December 1941, the Federal government recognized immediately that certain consumer products that Americans took for granted would either become very scarce or completely inaccessible if it didn’t step in and restrain the American consumer. Rubber, sugar, alcohol, cigarettes, and gasoline topped the list.

Why rubber? Most of America’s rubber came from the Dutch East Indies (today’s Indonesia), and the Japanese invasion of those islands severed America’s supply. Without rubber, tires couldn’t be produced that would become essential in the war effort. As American car manufacturers shifted to production of planes, tanks, and Jeeps, rubber rationing began, followed closely by gasoline. The thinking was, if Americans didn’t have gasoline, they wouldn’t drive, thus decreasing the need for new tires and rubber.

To further decrease the rubber demand, no new cars were manufactured after January 1, 1942, while all automobile racing ceased. There was no Indianapolis 500 from 1942 through 1945.

We should take comfort that Americans 80 years ago didn’t like the idea of going without gasoline any more than we do now. The government first tried making gasoline rationing voluntary in the early months of 1942, and that worked out about as well as you’d imagine.

So on May 15, 1942–ironically, 79 years ago this week—gasoline rationing began in 17 Eastern states and was in effect in all 48 states by the end of the year.

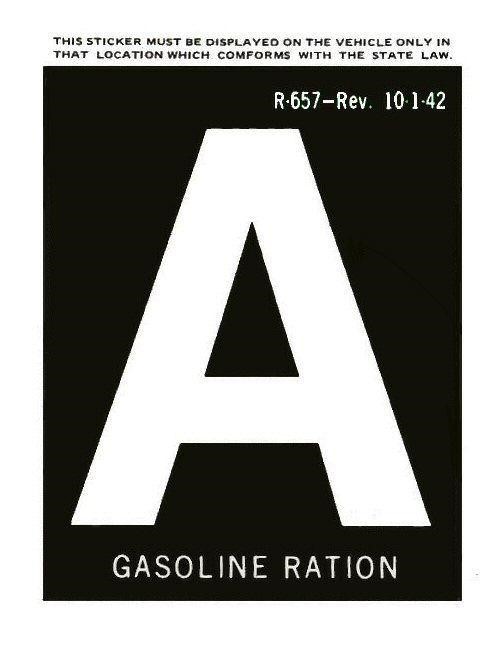

How did it work? Local rationing boards—over 5,000 of them across the country—oversaw the process and reported to the Office of Price Administration (known as the OPA) in Washington. Depending on your job, you received a colored sticker or card with a letter printed on it that you then placed on your windshield.

Most Americans got “A” cards, signifying the lowest priority and only 3 to 4 gallons of gas a week. Those in the military and industry got “B” stickers and up to 8 gallons a week. Doctors and others deemed essential to the war effort received “C” stickers, truckers got “T,” while those deemed most essential—clergy, police, firemen, mail carriers, and civil defense workers, got the coveted “X” stickers and unlimited gasoline. It didn’t take long for most Americans to start referring to the OPA derisively as “Only a Puny A-card.”

Lest we think the Greatest Generation was somehow more virtuous, it’s worth noting that there was a brisk underground market for upgrading one’s sticker for the right price. Rationing stamp books were also bought and sold illegally for those who found it hard to get things like sugar, meat, flour, and tobacco. And it won’t surprise you that 200 Congressmen tried to give themselves “X” stickers, but the ensuing outrage cancelled that idea, even without Twitter. Some things never change.

Thinking about all of this as I watched people lining up at Racetrac to panic buy before the last drop of fuel disappeared from the planet—or until the Colonial Pipeline flows once again—I couldn’t help but wonder how contemporary Americans would react to being asked for the kind of sacrifice that prevailed in World War II.

In our highly polarized country where distrust of the government is legion, it’s a given that gas-rationing would become highly politicized. One can imagine local rationing boards in some states simply refusing to meet, refusing to limit the amount of gas to people in their communities, and inviting their residents to drive down to the local QT and demand a full tank, regardless of their sticker. Gas equals freedom!! Let’s pause for a moment to imagine the viral videos of confrontations between gas sellers and consumers that would roil the Internet. Can you envision NASCAR shutting down or Americans going without new cars for three years?

I also pondered future shortages created by cyberterrorist attacks. What if the supply lines for whatever smart phones are made of are suddenly strangled? What about the life-giving transmission of coffee beans to Starbucks and elsewhere? If the world’s hops supply is interrupted (gasp!), would the beer pipeline shut down? Can you imagine the lines and fistfights at the Golden Gallon if that happens?

I know, I know—c’mon Stan, don’t joke about this. Cyberterrorism is real, it’s nothing to laugh at. To quote Abraham Lincoln, criticized for making jokes in cabinet meetings during the Civil War, I laugh because I must not cry.

Not to mention, when the great beer-rationing crisis comes, I’m sure I’ll get Only a Puny A-card. That’s when I’ll break out my government-rationed crying towel.

I’m making merry only because these and similar catastrophes are bound to happen—and when they do, we, all by ourselves, with no help from any outside source, will make it much worse than it should be. We always do.

Nancy Wilson Ross put it best: “When man conquers space, his ancient, universal, and perpetual problem will remain the same as it has been from the very beginning—to conquer himself.”