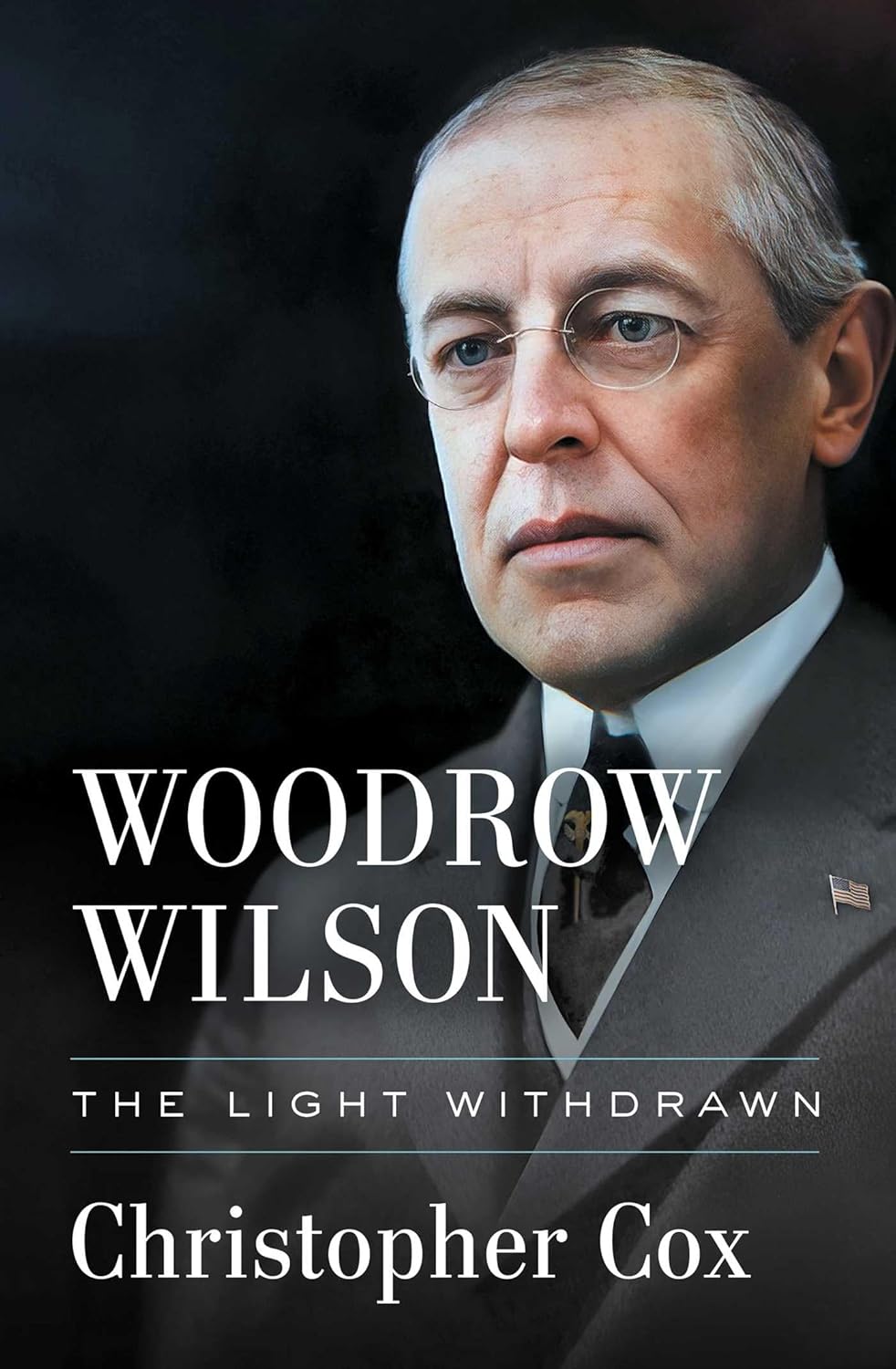

This week Stan talks to Christopher Cox, Senior Scholar in Residence at the University of California, Irvine, about his new book, Woodrow Wilson: The Light Withdrawn, published in 2024 by Simon & Schuster. Cox’s focus is on Wilson’s role in the movements for women’s suffrage and racial equality, and his open hostility to both. This is a riveting, beautifully written reassessment of the heroes who fought so hard for decades to pass the Susan B. Anthony Amendment more than a century ago—and Wilson’s legacy in our own day.