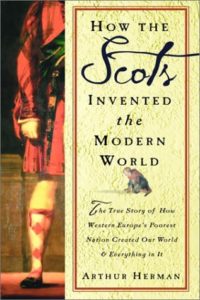

How the Scots Invented the Modern World: The True Story of How Western Europe’s Poorest Nation Created Our World & Everything in It by Arthur S. Herman (Crown Publishing, 2001, 472 pp.).

How the Scots Invented the Modern World: The True Story of How Western Europe’s Poorest Nation Created Our World & Everything in It by Arthur S. Herman (Crown Publishing, 2001, 472 pp.).

The Enlightenment is one of my favorite periods in history, as writers and thinkers like Voltaire pushed back hard against the orthodox boundaries that had shackled human minds for centuries. That didn’t start or end with the Enlightenment of course, but it certainly reached its apogee then, in my uninformed opinion. While reading Dennis Rasmussen’s new book, The Infidel and the Professor: David Hume, Adam Smith, and the Friendship that Shaped Modern Thought (Princeton University Press, 2017) I came across the title of this book about the Scottish Enlightenment. The Scottish Enlightenment would have been better chosen as a title for this book, by the way. The existing title is a little too hyperbolic, as many reviewers have pointed out. Why does nearly every non-fiction book published these days by a commercial press have a subtitle that makes such ludicrous claims? You’ve seen them: The Flatulent Toad: How One Peasant’s Quest for Flavored Ice Cream Led to the Invention of Pepto-Bismol, The Atomic Bomb, and Everything Else You Could Possibly Imagine. Enough already. Title aside, this book covers 200 years of history and makes a very compelling case for the importance of Scots and their descendants in nearly every major undertaking of modern society, from education to technology to law, government, and religion. I’m not totally convinced by a long shot, but it’s a thought-provoking book with an endlessly fascinating cast of characters, from John Knox to David Hume, Adam Smith, Thomas Telford, and Walter Scott, to Andrew Jackson and Andrew Carnegie, all of whom you’re left wanting to know more about through further reading and exploration. Luckily for us there’s a wealth of riches to choose from: Nicholas Phillipson’s recent biography Adam Smith: An Enlightened Life (Yale, 2012); Ernest Mossner’s The Life of David Hume (Clarendon, 2001), Julian Glover’s Man of Iron: Thomas Telford and the Building of Britain (Bloomsbury, 2017) and John Prebble’s highly partisan but classic Fire and Sword trilogy about the Highland Scots: Culloden (1961), The Highland Clearances (1963), and Glencoe (1966). More books to buy!