August is here, and that means all sorts of things. For Braves fans, it means you brace yourself for the Annual August Flop, and sure enough, right on schedule, the swoon has begun. For college football fans, it means the long wait is almost over. And for we happy yet sweating denizens of Charm City, it means breaking out the kayaks for the evening commute after the drenching, frog-strangling storms that drop 3 inches of rain in 20 minutes every afternoon, hard on the heels of three-digit heat indices.

August is here, and that means all sorts of things. For Braves fans, it means you brace yourself for the Annual August Flop, and sure enough, right on schedule, the swoon has begun. For college football fans, it means the long wait is almost over. And for we happy yet sweating denizens of Charm City, it means breaking out the kayaks for the evening commute after the drenching, frog-strangling storms that drop 3 inches of rain in 20 minutes every afternoon, hard on the heels of three-digit heat indices.

August also means that, despite the unrelenting heat and humidity, summer is winding down. The unofficial end is a mere two weeks away on Labor Day but if you define summer by summer “vacation,” it’s already over at my house, where school started on August 7. It was 96 degrees that day, by the way. There’s lots of things wrong with that, but then nobody asked me if we should start school that early. If you define summer by temperature, summer in Savannah will last at least 3 more months. But let’s not turn this essay into another rant about the weather, shall we?

I’ve always found the notion of “summer reading,” once you’re out of K-12 or college, to be a relatively useless term. What adult has more time to read in summer than in any other season? Unless you are blessed—and I won’t name any names or occupations—to not have to work in the summer, I’ll wager you actually have less time to read in that season than in any other. The kids are out of school and they keep you busy. Longer days mean more time to do things outside and probably less time reading. Weekends are filled with yard work and other more pleasurable outdoor activities. Personally, I find the cooler afternoons and longer nights of autumn and winter to be more conducive to reading, but that’s just me. I suspect the notion of having more time to read in summer comes from “beach reading” that publishers like to promote, and the lofty idea that people take along stacks of books and actually read when they’re on vacation. If you read the rest of the year, you probably read on vacation. If you’re not a reader, you won’t read on the beach or anywhere else you vacate to. Readers read, no matter the season.

I’ve always found the notion of “summer reading,” once you’re out of K-12 or college, to be a relatively useless term. What adult has more time to read in summer than in any other season? Unless you are blessed—and I won’t name any names or occupations—to not have to work in the summer, I’ll wager you actually have less time to read in that season than in any other. The kids are out of school and they keep you busy. Longer days mean more time to do things outside and probably less time reading. Weekends are filled with yard work and other more pleasurable outdoor activities. Personally, I find the cooler afternoons and longer nights of autumn and winter to be more conducive to reading, but that’s just me. I suspect the notion of having more time to read in summer comes from “beach reading” that publishers like to promote, and the lofty idea that people take along stacks of books and actually read when they’re on vacation. If you read the rest of the year, you probably read on vacation. If you’re not a reader, you won’t read on the beach or anywhere else you vacate to. Readers read, no matter the season.

But the term “summer” reading also refers to seasonal reading, of course, and this idea has more traction–we read different things at different times of the year. Is that true for you? I wrote an essay for this blog last October about some great books to read around Halloween, and there are any number of books that make great reading during the Christmas season and on cold winter nights. Here’s what I’ve been reading this summer, broadly defined as Memorial Day to Labor Day:

World War I: With the 100th anniversary of the start of the war upon us this month, there is lots of good new scholarship being published on all aspects of the conflict. Here’s a few that I’ve picked up recently: Christopher Clark’s The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914; Geoffrey Wawro, A Mad Catastrophe: The Outbreak of World War I and the Collapse of the Habsburg Empire; David Crane, Empires of the Dead: How One Man’s Vision Led to the Creation of World War I’s War Graves; Britt Buttar, Collision of Empires: The War on the Eastern Front, 1914; Max Hastings, Catastrophe 1914: Europe Goes to War; Margaret Macmillan, The War That Ended Peace: The Road  to 1914; and Sean McMeekin’s July 1914: Countdown to War.

to 1914; and Sean McMeekin’s July 1914: Countdown to War.

This is a just a short list of some of the new stuff that’s out, and if it’s any indication, there’ll be a slew of new books over the next four years to mark the centennial of the Marne, the Somme, Flanders, Verdun, the Argonne, and Versailles, not to mention reassessments of all other aspects of battles, the carnage and personalities involved, and the war on the home front and its aftermath.

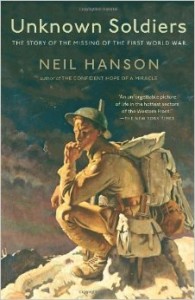

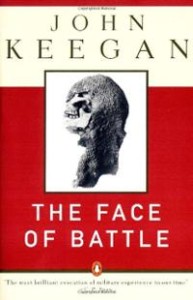

I’m giving a couple of upcoming talks on the centennial of the First World War, so I used that as an excuse not to dig into the new books but to re-read three compelling books that I enjoyed the first time around and that I now consider classics: Unknown Soldiers: The Story of the Missing of the First World War (Knopf, 2005) by Neil Hanson; Back to the Front: An Accidental Historian Walks the Trenches of World War I (Avon, 1996) by Stephen O’Shea; and John Keegan’s The Face of Battle (Penguin, 1976). Keegan’s account of Agincourt, Waterloo, and the Somme is the best known, but all three offer riveting accounts of the slaughter of an entire generation and the scar the Great War left on the 20th century.

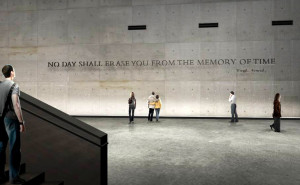

I’m giving a couple of upcoming talks on the centennial of the First World War, so I used that as an excuse not to dig into the new books but to re-read three compelling books that I enjoyed the first time around and that I now consider classics: Unknown Soldiers: The Story of the Missing of the First World War (Knopf, 2005) by Neil Hanson; Back to the Front: An Accidental Historian Walks the Trenches of World War I (Avon, 1996) by Stephen O’Shea; and John Keegan’s The Face of Battle (Penguin, 1976). Keegan’s account of Agincourt, Waterloo, and the Somme is the best known, but all three offer riveting accounts of the slaughter of an entire generation and the scar the Great War left on the 20th century.  Hanson’s book in particular highlights how the unprecedented carnage of 37 million casualties changed the way societies memorialize the men who fought and died, and how those memorials institutionalize the trauma of coming to terms with the hundreds of thousands who have no known grave. All are highly recommended as we contemplate the continuing meaning of the Great War in our lives.

Hanson’s book in particular highlights how the unprecedented carnage of 37 million casualties changed the way societies memorialize the men who fought and died, and how those memorials institutionalize the trauma of coming to terms with the hundreds of thousands who have no known grave. All are highly recommended as we contemplate the continuing meaning of the Great War in our lives.

The Great Books: In 2008 I subscribed to Easton Press’s list of the “100 Greatest Books Ever Written,” and I read three offerings this summer: Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus by Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley; Fathers and Sons by Ivan Turgenev; and The Red and the Black by Stendhal. Shelley’s gothic novel, first published in 1818, is not at all like the camp versions served up by Hollywood, which is a real shame. It seems to me that there have been many missed opportunities to get this story about the creation of life and what, in the end, makes us human, on film.  I remember the 1973 made-for-TV movie, Frankenstein, the True Story, though critically lampooned, as coming closer to the novel than Boris Karloff ever did. Stendhal’s work is rightly hailed as a groundbreaking novel, one of the first to explore the psychological dimensions of its multi-layered characters. The three books each feature some of the most memorable characters in literature: Victor Frankenstein and his unnamed Creature (not at all like the Golem featured in films); the young Nihilist physician Bazarov in Turgenev’s 1862 novel of generational conflict; and the ambitious climber Julien Sorel in Stendhal’s 1830 realistic classic. Are they three of the greatest books ever written? Read and decide for yourself.

I remember the 1973 made-for-TV movie, Frankenstein, the True Story, though critically lampooned, as coming closer to the novel than Boris Karloff ever did. Stendhal’s work is rightly hailed as a groundbreaking novel, one of the first to explore the psychological dimensions of its multi-layered characters. The three books each feature some of the most memorable characters in literature: Victor Frankenstein and his unnamed Creature (not at all like the Golem featured in films); the young Nihilist physician Bazarov in Turgenev’s 1862 novel of generational conflict; and the ambitious climber Julien Sorel in Stendhal’s 1830 realistic classic. Are they three of the greatest books ever written? Read and decide for yourself.

Autobiography: Washington Post book reviewer and Pulitzer Prize winner Michael Dirda is one of my favorite writers and I’ve devoured everything he’s published. He is, in my humble opinion,  the best American literary critic writing today; you can find him every Wednesday in the Post, the New York Review of Books, and online on The American Scholar and Barnes and Noble reviews. His books of essays have brought dozens of great reads into my life—new ones and overlooked classics. This summer I came across a copy of his memoir, An Open Book: Growing up in the Heartland (2003), a heartfelt tribute to a lifelong love of reading and the printed word that began in Lorain, Ohio. If you haven’t already, get to know Michael Dirda.

the best American literary critic writing today; you can find him every Wednesday in the Post, the New York Review of Books, and online on The American Scholar and Barnes and Noble reviews. His books of essays have brought dozens of great reads into my life—new ones and overlooked classics. This summer I came across a copy of his memoir, An Open Book: Growing up in the Heartland (2003), a heartfelt tribute to a lifelong love of reading and the printed word that began in Lorain, Ohio. If you haven’t already, get to know Michael Dirda.

History: Nature’s God: The Heretical Origins of the American Republic by Matthew Stewart (W.W. Norton, 2014) A full review of this book is forthcoming on this blog, but suffice it to say that this is a very controversial book (or will be to many people who read it) and is a full-throated rebuttal to those who insist that the United States was founded by Christians as a  Christian nation. Read this one and discuss with your book club if you want to liven things up.

Christian nation. Read this one and discuss with your book club if you want to liven things up.

Bedtime Reading: Finally, what to read before turning out the lights? I save the heavy stuff for the early mornings. Clifton Fadiman, he of The Lifetime Reading Plan fame, wrote in his 1955 essay, “Pillow Books,” that bedtime reading should be chosen carefully. “I hold with neither the Benzedrine nor the Seconal school,” he declared. “As for the first, to read the whole night through is to trespass upon nature. The dark hours belong to the unconscious, which has its own rights and privileges. To use the literary lockout against the unconscious is unfair to the dreamers’ union. Hence the wise bed reader, rendering unto Morpheus the things that are Morpheus’, will shun any book that appears too interesting.”

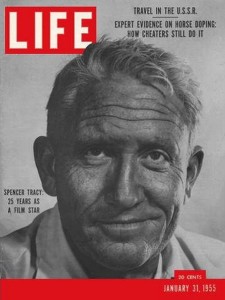

The ideal bedtime book, he says, should neither bore nore excite. Wise advice. So at night this summer I turned to Erle Stanley Gardner’s The Case of the Half-Wakened Wife, # 27 in the Perry Mason series, first published in 1945, and containing the usual cast of characters—the erstwhile counselor Perry, his girl Friday (and sometime love interest) Della Street, detective and Mason sidekick Paul Drake, and the pompous and overbearing DA, Hamilton Burger. The literary Perry Mason cracks jokes, smokes, curses, enjoys a drink, and is occasionally profane. Why Raymond Burr was ever cast as television’s Perry Mason, I’ll never know. I find Gardner’s Mason to be much more human than the unbending Burr ever was on screen. All the stories in the Perry Mason series are interesting but easy to put down and pick up the next night without losing your place. Ideal for pillow reading.

The ideal bedtime book, he says, should neither bore nore excite. Wise advice. So at night this summer I turned to Erle Stanley Gardner’s The Case of the Half-Wakened Wife, # 27 in the Perry Mason series, first published in 1945, and containing the usual cast of characters—the erstwhile counselor Perry, his girl Friday (and sometime love interest) Della Street, detective and Mason sidekick Paul Drake, and the pompous and overbearing DA, Hamilton Burger. The literary Perry Mason cracks jokes, smokes, curses, enjoys a drink, and is occasionally profane. Why Raymond Burr was ever cast as television’s Perry Mason, I’ll never know. I find Gardner’s Mason to be much more human than the unbending Burr ever was on screen. All the stories in the Perry Mason series are interesting but easy to put down and pick up the next night without losing your place. Ideal for pillow reading.

Just for fun I tossed in P.G. Wodehouse’s The Inimitable Jeeves, a collection of short stories first published in in 1921 in the Strand Magazine. For those of you not blessed to have made their acquaintance, all the stories involve English gentleman/socialite/fop Bertie Wooster, his humble but all-knowing valet Jeeves, and Bertie’s friend and fellow Drones Club member Bingo Little. This was the second collection of Jeeves stories published, following My Man Jeeves, with the celebrated first chapter, “Jeeves Exerts the Old Cerebellum.” Wodehouse was the unparalled master at British Upper Crust Old Boy humor, and his stories have a charm, lightness, and hilarity all their own. There is a whole other universe in Wodehouse’s writing, and it’s all perfect for perusing just before turning out the lights.

Just for fun I tossed in P.G. Wodehouse’s The Inimitable Jeeves, a collection of short stories first published in in 1921 in the Strand Magazine. For those of you not blessed to have made their acquaintance, all the stories involve English gentleman/socialite/fop Bertie Wooster, his humble but all-knowing valet Jeeves, and Bertie’s friend and fellow Drones Club member Bingo Little. This was the second collection of Jeeves stories published, following My Man Jeeves, with the celebrated first chapter, “Jeeves Exerts the Old Cerebellum.” Wodehouse was the unparalled master at British Upper Crust Old Boy humor, and his stories have a charm, lightness, and hilarity all their own. There is a whole other universe in Wodehouse’s writing, and it’s all perfect for perusing just before turning out the lights.

Which it’s time to do for this column. Turn the page and enjoy the rest of your summer.