This edition of Off the Deaton Path’s podcast: Robert Johnson, Jim Croce, The Blues, the Devil, Lynching, Notable Passings, Fun Facts Known By Few, The Worst Invention Known to Man, and so much more……

Category Archives: Books

New Podcast: Hitler

Check out Stan’s first podcast on Off the Deaton Path, a new weekly feature. In the wake of the protests and violence in Charlottesville, this week he discusses a riveting new biography of Hitler.

Crush the Infamous

Heather Ann Thompson, Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy. Pantheon Books, 2016, 724 pp., $35.00.

At the Henry W. Grady School of Journalism at the University of Georgia, the late great Conrad Fink—Marine lieutenant, former Vietnam War correspondent, Associated Press veteran, and journalist par excellence—taught us that above all our mission was to “comfort the afflicted, and to afflict the comfortable,” to shine the light in dark places. Wherever things are done—for good or evil—by public institutions, he said, they are done in the name of the people of this republic, and therefore the people will always have a right to know what is done in their name.

At the Henry W. Grady School of Journalism at the University of Georgia, the late great Conrad Fink—Marine lieutenant, former Vietnam War correspondent, Associated Press veteran, and journalist par excellence—taught us that above all our mission was to “comfort the afflicted, and to afflict the comfortable,” to shine the light in dark places. Wherever things are done—for good or evil—by public institutions, he said, they are done in the name of the people of this republic, and therefore the people will always have a right to know what is done in their name.

In a similar vein, Voltaire long ago taught us that we should always rage against injustice, and that those in authority will forever bear watching because they will abuse that power. When they do, call them to account for it in the strongest terms possible. Theodore Besterman, the legendary Voltaire scholar, said of his subject’s life’s work, “Voltaire did not destroy injustice, but he took the first step, he put the unjust on the defensive.” Voltaire’s motto toward the end of his life? “Crush the infamous.”

In the finest sense of both of these charges, Heather Ann Thompson has fulfilled that mission and has shined a bright light on one of the darkest places imaginable and one of the most disturbing episodes in American history, the 1971 Attica prison uprising and its aftermath. She has put injustice on the defensive and in so doing has won the 2017 Pulitzer Prize for history.

First, a full disclosure: Heather Ann Thompson is my friend. I’ve known her and her husband Jon Wells for years, and they’re both great scholars and terrific people, so I can’t pretend to be impartial about this book. I think it’s great and would like it had it won nothing but the Irving Forbush Prize.

Jon Wells for years, and they’re both great scholars and terrific people, so I can’t pretend to be impartial about this book. I think it’s great and would like it had it won nothing but the Irving Forbush Prize.

But of course you don’t have to take my word for it. The 2017 Pulitzer judges awarded this book the prize for history for “a narrative history that sets high standards for scholarly judgment and tenacity of inquiry in seeking the truth about the 1971 Attica prison riots.”

Tenacity of inquiry is putting it mildly. The state of New York has had a vested interest for over 45 years in making sure the truth of what happened at Attica—during the takeover by the inmates, during the retaking by the state, and the fallout afterward—never sees the light of day.

Why would this be so? The state’s actions at Attica—taken in the name of the people—should have been able to bear the scrutiny of the most thorough investigation. As Thomas Jefferson said, “It is error alone which needs the support of government. Truth can stand on its own.”

But this has never been the case. From that day to this, the highest officials in the state of New York have done their best to make sure that the real story of this tragic episode never got out. It defies understanding how an entirely different generation of people, many of whom were not even born in 1971, could still be complicit in continuing to cover up the truth about Attica. And yet the documentary and artifactual evidence of what happened during the five days of September 9-13, 1971, and for years afterward, has been distorted, hidden away, or deliberately destroyed.

In a truly remarkable achievement of historical research and journalistic detective work, Heather relentlessly pursued the story of Attica using every weapon at her disposal to uncover the full story of the Attica uprising, the state’s brutal retaking of the prison that killed both hostages and inmates, and the barbaric retaliation meted out to prisoners in the days, months, and years afterwards. Martin Luther King, Jr. famously said that “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” In light of the Attica story, one wonders.

In the months leading up to September 1971, many of Attica’s prisoners petitioned and crusaded for better conditions at the prison, to no avail. On the morning of Thursday, September 9, in an uprising that was totally unplanned and unrehearsed, prisoners seized a chaotic moment in which a door was unexpectedly locked to rise up in protest against prison conditions and within hours nearly 1,300 inmates had taken control of Attica Correctional Facility. Seizing state and civilian hostages working at the prison (who naturally feared for their lives but who were protected by the inmates), prisoners negotiated with state authorities for basic civil and human rights that they felt they’d too long been denied. With tensions mounting and fears for the hostages safety, Governor Nelson Rockefeller sent the New York State Police and Attica’s Correctional Officers in with tear gas raining down and guns blazing.

Twenty-nine inmates and ten hostages were killed, all by state authorities, and over a hundred more were shot. In the bloody aftermath the state retaliated unmercifully for the uprising by torturing prisoners with sadistic acts and denying them adequate medical care. The officials also lied to hostage families about who killed their loved ones, and to the American public about what really happened. From Governor Rockefeller on down, the state went to extraordinary lengths to cover up official actions, protect state police from criminal charges, all while denying any official culpability for mental and physical damage inflicted on hostage and inmate survivors and their families that continues to this day.

It’s a shameful story that Heather has dragged kicking and screaming into the light of day through Freedom of Information requests, interviews with survivors, over a decade of dogged research in archives across the country, and sheer determination to not let this story remain hidden from the public any longer. In addition to the adulation and prizes, she’s also received threats and been vilified.

As you would expect from a prize winner, this book is a compelling, page-turning read, but make no mistake: some of the graphic descriptions of what happened at Attica will—and should—turn your stomach.

The author’s attention to the smallest details is impressive. Just two examples among hundreds: on the morning the uprising began, Heather describes a moment when the inmates battered down a gate that didn’t just give way; one of the bars securing the gate to the cement “broke in half about fifteen inches down from the ceiling” (p. 54), a small nugget gleaned from a close reading of a very long after-action report. Similarly, after the retaking, inmates struggled to get word out to loved ones that they were alive, if not safe from state retribution and retaliation. They smuggled a red spiral-bound notebook from cell to cell, into which inmates wrote notes to family members in hopes it would get over the walls. State police confiscated it, and 40 years later Heather held it in her hands in a warehouse of the New York State Museum, its messages finally seeing the light of day. The notebook and the rest of the documents and artifacts she saw in that warehouse have subsequently disappeared.

After years of litigation, the state of New York finally settled with a group of former Attica prisoners in 2000, and with surviving hostages and their families in 2005. To date there have been no official apologies or admissions of wrong-doing, and no trooper or correctional officer was ever charged with a crime for their actions during the re-taking.

Blood in the Water isn’t just about what happened in 1971, of course. As we continue to live in the era of mass incarceration, the populations of this country’s ever-expanding prisons receive the least sympathy/empathy/understanding of all our fellow human beings. It’s customary for us to turn away from what happens behind those walls, secure in the knowledge that “whatever they get, they deserve. They should have thought about that before they raped, murdered, shot, stole, or…..” whatever else “they” did. When prison rebellions occur, our collective response isn’t to try to understand why, it’s to crack down even harder on the system and those in it.

What civil or human rights, after all, do convicted criminals have? That question always reminds me of the exchange between William Roper and Sir Thomas More in A Man For All Seasons, when Roper says he would cut down every law in England to get to the Devil. More replied, “And when the last law was down, and the Devil turned ’round on you, where would you hide, the laws all being flat? Yes, I’d give the Devil benefit of law, for my own safety’s sake!”

As Attica and its aftermath make clear, in a nation that holds any moral claims to standing for basic human rights, we turn a blind eye to what is done in our name—in prisons or anywhere else—at our own peril. This book is a reminder to we who need reminding that indifference to injustice and human suffering is obscene and immoral, no matter the source, and that in a self-governing republic power must always be held accountable.

As Voltaire said, “Every man is guilty of the good he did not do.”

O Lost, and By the Wind Grieved

So my end-of-the year wrap-up blog is over two weeks late. That’s in part because I took a moment to enjoy the four days of cold weather that descended upon Savannah two weeks ago. Have no fear, this isn’t going to descend into another rant about the weather, but winter this year in Savannah was apparently scheduled for the four days surrounding that weekend, and I paused to enjoy it. It’s now spring again, here in mid January. Air-conditioners are running, trees are blooming, and grass will soon be growing and in need of trimming. Atlanta missed a record high on Christmas Eve by one degree, and came perilously close on Christmas Day. That’s two years in a row that bathing suits have been more in order at Yuletide than sweaters, and yours truly doesn’t like it. I don’t like it all. Okay, so it turned into a short rant about the weather. Sorry.

One good thing about delaying this column is that it gives me a chance to congratulate the Atlanta Falcons for winning their division, locking up the second seed in the NFC playoffs, a first-round bye, and a divisional win over the Seattle Seahawks. The rematch with the Green Bay Packers in this weekend’s NFC championship game will be a good one. Stay tuned.

We can also congratulate the Clemson Tigers on knocking off the top-ranked Alabama Crimson Tide (after shutting out Ohio State) and winning the college football national championship. It’s not easy to beat Urban Meyer and Nick Saban, as Clemson did in this year’s playoff. The Tigers needed nearly all 60 minutes to beat Bama, but when it was over they had won their first national title in 35 years, thanks in large part to Gainesville native Deshaun Watson. How the Georgia schools let him get away is beyond me, but there he was wearing orange and purple and standing on the championship stage afterward. My prediction: Bama will be back in the playoff next year, and Clemson will be at home watching, with Watson and lot of other talent moving on. Everyone else has to rebuild; Saban just reloads and starts shooting again.

We can also congratulate the Clemson Tigers on knocking off the top-ranked Alabama Crimson Tide (after shutting out Ohio State) and winning the college football national championship. It’s not easy to beat Urban Meyer and Nick Saban, as Clemson did in this year’s playoff. The Tigers needed nearly all 60 minutes to beat Bama, but when it was over they had won their first national title in 35 years, thanks in large part to Gainesville native Deshaun Watson. How the Georgia schools let him get away is beyond me, but there he was wearing orange and purple and standing on the championship stage afterward. My prediction: Bama will be back in the playoff next year, and Clemson will be at home watching, with Watson and lot of other talent moving on. Everyone else has to rebuild; Saban just reloads and starts shooting again.

Another Goodbye to Another Good Friend: If you’re on social media at all, then you know that 2016 went down as one of the most unpopular years in recent memory, if we could take votes on such things. It was certainly a bad year for deaths in the entertainment industry, as you no doubt noticed yourself and as many other people have pointed out. The deaths of David Bowie, Prince, Glenn Frey, and many others left a huge void, and they’ve all been lovingly remembered and mourned on cultural and social media. There were many other famous passings, from Muhammad Ali to Nancy Reagan.

But lost among all those big names were some lesser stars in the firmament that you may or may not have heard of but should have. We’ll pause for a moment here and take one last look back at some other folks who shook off this mortal coil in 2016:

Though you may have missed it, Thomas Jefferson died in 2016, 190 years after his first death. Okay, so it wasn’t that Jefferson. But all the millions of fans of the movie musical 1776—of which I happen to be one—fondly remember Ken Howard’s lighthearted portrayal of Thomas Jefferson, long before he became The White Shadow on TV. The Tony- and Emmy-award-winning Howard died on March 23 at age 71.

Though you may have missed it, Thomas Jefferson died in 2016, 190 years after his first death. Okay, so it wasn’t that Jefferson. But all the millions of fans of the movie musical 1776—of which I happen to be one—fondly remember Ken Howard’s lighthearted portrayal of Thomas Jefferson, long before he became The White Shadow on TV. The Tony- and Emmy-award-winning Howard died on March 23 at age 71.

Horace Ward, born in LaGrange, Georgia, was the first African American to attempt to batter down the wall of segregation that prevented black students from attending the University of Georgia. In 1950 he applied to UGA Law School and was turned down, despite a stellar undergraduate career at Morehouse and Atlanta University. Ward tried and failed for nearly a decade to overturn the decision in court, but his case helped eventually to end segregation at Georgia’s flagship university after 175 years, when Hamilton Holmes and Charlayne Hunter were admitted in 1961. Ward went on to become the first African American ever to serve on the federal bench in Georgia, though he shamefully had to go elsewhere to earn his law degree. Judge Horace Taliaferro Ward died at the age of 88 on April 23 and is buried in Atlanta’s Westview Cemetery.

Horace Ward, born in LaGrange, Georgia, was the first African American to attempt to batter down the wall of segregation that prevented black students from attending the University of Georgia. In 1950 he applied to UGA Law School and was turned down, despite a stellar undergraduate career at Morehouse and Atlanta University. Ward tried and failed for nearly a decade to overturn the decision in court, but his case helped eventually to end segregation at Georgia’s flagship university after 175 years, when Hamilton Holmes and Charlayne Hunter were admitted in 1961. Ward went on to become the first African American ever to serve on the federal bench in Georgia, though he shamefully had to go elsewhere to earn his law degree. Judge Horace Taliaferro Ward died at the age of 88 on April 23 and is buried in Atlanta’s Westview Cemetery.

On April 22, 1945, Jerry O’Keefe of Ocean Spring, Mississippi, shot down five Japanese planes over Okinawa in his first aerial dogfight. He was 21 years old. After the war he went into the insurance business and became mayor of Biloxi, where—Mississippi born and bred—he faced down and arrested members of the Ku Klux Klan who marched there without a permit. The Klan sent him death threats and burned a cross on his lawn. The warrior who earned the Air Medal, the Navy Cross, the Distinguished Flying Cross, and the Congressional Gold Medal died on August 23 at age 93.

On April 22, 1945, Jerry O’Keefe of Ocean Spring, Mississippi, shot down five Japanese planes over Okinawa in his first aerial dogfight. He was 21 years old. After the war he went into the insurance business and became mayor of Biloxi, where—Mississippi born and bred—he faced down and arrested members of the Ku Klux Klan who marched there without a permit. The Klan sent him death threats and burned a cross on his lawn. The warrior who earned the Air Medal, the Navy Cross, the Distinguished Flying Cross, and the Congressional Gold Medal died on August 23 at age 93.

It took William H. McNeill ten years to write The Rise of the West: A History of the Human Community, but after its publication in 1963 it became a surprising best seller and won the National Book Award for history and biography. As Clifton Fadiman said, it is “deeply reflective, the work of a master scholar.” Hugh Trevor-Roper, no slouch himself, called it “the most learned…the most intelligent…the most stimulating and fascinating book that has ever set out to recount and explain the whole history of mankind.” It remains unsurpassed in scope and breadth, one of 20 books that McNeill wrote in a long and distinguished career. If you haven’t read it, you should. McNeill died on July 8 at 98.

Andy Griffith fans everywhere (like me) have Richard Linke to thank for Griffith’s discovery and the TV show that brought him worldwide fame as the mighty sheriff of Mayberry. While working for Capitol Records, Linke was sitting by his radio one clear night in 1953 when he picked up a southern station broadcasting Griffith’s recording of “What it Was, Was Football.” Linke knew something special when he heard it. He flew immediately to North Carolina, bought the rights to the record for Capitol for $10,000, signed Griffith to a contract, and managed his career for the rest of his life. As Griffith put it, “had it not been for him, I would have gone down the toilet.” Linke died on June 15 at 98.

Andy Griffith fans everywhere (like me) have Richard Linke to thank for Griffith’s discovery and the TV show that brought him worldwide fame as the mighty sheriff of Mayberry. While working for Capitol Records, Linke was sitting by his radio one clear night in 1953 when he picked up a southern station broadcasting Griffith’s recording of “What it Was, Was Football.” Linke knew something special when he heard it. He flew immediately to North Carolina, bought the rights to the record for Capitol for $10,000, signed Griffith to a contract, and managed his career for the rest of his life. As Griffith put it, “had it not been for him, I would have gone down the toilet.” Linke died on June 15 at 98.

Producer and arranger Milt Okun performed a similar service for music fans. He helped create the Chad Mitchell Trio and when Mitchell left in 1965, Okun discovered and hired Henry John Deutschendorf, Jr. to replace him. Okun turned John Deutshchendorf into John Denver and produced and published the music that made him a folk and pop legend. The man who gave the world the musical gift of the Bard of the Rocky Mountains died on November 15 at age 92.

Producer and arranger Milt Okun performed a similar service for music fans. He helped create the Chad Mitchell Trio and when Mitchell left in 1965, Okun discovered and hired Henry John Deutschendorf, Jr. to replace him. Okun turned John Deutshchendorf into John Denver and produced and published the music that made him a folk and pop legend. The man who gave the world the musical gift of the Bard of the Rocky Mountains died on November 15 at age 92.

If you’re a fan of classic cartoons like me, you’ve heard the voice of Janet Waldo all of your life. She was the female Mel Blanc, bringing dozens of animated characters to life over the last 60 years, from Josie in “Josie and the Pussycats,” to Judy Jetson, Penelope Pitstop, and Fred Flintstone’s mother-in-law. She died on June 12 at the age of 96.

And if you’re a devotee of classic movies, one death last year was especially notable: Madeleine Lebeau was 19 years old when she was cast as Yvonne in Casablanca, and she achieved screen immortality by singing “La Marseillaise” with tears streaming down her face. When she died on May 1 at age 92, the French culture minister Audrey Azoulay said, “She will forever be the face of French resistance.” Lebeau was the last surviving credited cast member of what is arguably the best film ever made.

And if you’re a devotee of classic movies, one death last year was especially notable: Madeleine Lebeau was 19 years old when she was cast as Yvonne in Casablanca, and she achieved screen immortality by singing “La Marseillaise” with tears streaming down her face. When she died on May 1 at age 92, the French culture minister Audrey Azoulay said, “She will forever be the face of French resistance.” Lebeau was the last surviving credited cast member of what is arguably the best film ever made.

There were other “lasts” who died in 2016: Bill Herz was the last surviving crew member of Orson Welles’ “War of the Worlds” 1938 radio broadcast that terrified listeners with the news of Martians invading New Jersey. Herz died on May 10 at 99.

Two other big-screen deaths of note: Fritz Weaver was an all-purpose actor who appeared in dozens of movies and TV shows since the 1950s, but to my mind his most notable role was as the paranoid Air Force Colonel Cascio, who refuses to help the Russians shoot down American planes in the 1964 Cold War thriller Fail Safe. Diehard “Twilight Zone” fans will remember him from the episodes “Third From the Sun” and “The Obsolete Man.” He died November 26 at age 90.

Two other big-screen deaths of note: Fritz Weaver was an all-purpose actor who appeared in dozens of movies and TV shows since the 1950s, but to my mind his most notable role was as the paranoid Air Force Colonel Cascio, who refuses to help the Russians shoot down American planes in the 1964 Cold War thriller Fail Safe. Diehard “Twilight Zone” fans will remember him from the episodes “Third From the Sun” and “The Obsolete Man.” He died November 26 at age 90.

Similar to Weaver, Frank Finlay had a long and distinguished career across the stage and screen, but every Christmas he returns as Jacob Marley’s ghost in the 1984 George C. Scott version of A Christmas Carol, the best of them all, in my humble and uninformed opinion. Finlay died on January 30 at 89.

Similar to Weaver, Frank Finlay had a long and distinguished career across the stage and screen, but every Christmas he returns as Jacob Marley’s ghost in the 1984 George C. Scott version of A Christmas Carol, the best of them all, in my humble and uninformed opinion. Finlay died on January 30 at 89.

The 1990s TV show “Homicide: Life on the Street” was groundbreaking television and is considered by many to be one of the best shows ever produced. I happen to be one of those people.  One of the finest episodes was Season Three’s “Crosetti,” which explored the suicide of Detective Steve Crosetti and its devastating impact on his fellow officers. Jon Polito played Crosetti for only two seasons but he left an indelible mark on the show, as well as the numerous characters he created as a stock player in several Coen Brothers’ films, including The Big Lebowski. He also played Jerry and Kramer’s landlord in the Season Nine “Seinfeld” episode “The Reverse Peephole.” Jon Polito died on September 1 at age 65.

One of the finest episodes was Season Three’s “Crosetti,” which explored the suicide of Detective Steve Crosetti and its devastating impact on his fellow officers. Jon Polito played Crosetti for only two seasons but he left an indelible mark on the show, as well as the numerous characters he created as a stock player in several Coen Brothers’ films, including The Big Lebowski. He also played Jerry and Kramer’s landlord in the Season Nine “Seinfeld” episode “The Reverse Peephole.” Jon Polito died on September 1 at age 65.

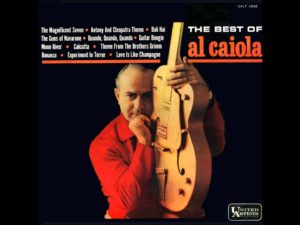

A personal memory: my mother had a wonderful and eclectic album collection when I was growing up, and one of my favorites was the steel guitar sounds of Al Caiola. You may think you don’t know him but you do: he recorded scores of instrumental versions of movie and TV show themes that became big hits and the soundtrack of a generation, most famously “The Magnificent Seven” and “Bonanza.” The next time you hear Paul Anka’s “Put Your Head on My Shoulder,” Neil Sedaka’s “Calendar Girl,” Bobby Darin’s “Mack the Knife” or “Splish-Splash,” Simon & Garfunkel’s “Mrs. Robinson,” Johnny Mathis’ “Chances Are,” Del Shannon’s “Runaway” and Ben E. King’s “Stand by Me,” you’re listening to the great guitarist who died in a New Jersey nursing home on November 9. He was 96.

A personal memory: my mother had a wonderful and eclectic album collection when I was growing up, and one of my favorites was the steel guitar sounds of Al Caiola. You may think you don’t know him but you do: he recorded scores of instrumental versions of movie and TV show themes that became big hits and the soundtrack of a generation, most famously “The Magnificent Seven” and “Bonanza.” The next time you hear Paul Anka’s “Put Your Head on My Shoulder,” Neil Sedaka’s “Calendar Girl,” Bobby Darin’s “Mack the Knife” or “Splish-Splash,” Simon & Garfunkel’s “Mrs. Robinson,” Johnny Mathis’ “Chances Are,” Del Shannon’s “Runaway” and Ben E. King’s “Stand by Me,” you’re listening to the great guitarist who died in a New Jersey nursing home on November 9. He was 96.

Finally, the man known to his legion of fans as The Hag died on his 79th birthday on April 6. As Keith Richards said, “One of the great country singers of all time and a helluva guitar player. Gonna miss you pal.”

Finally, the man known to his legion of fans as The Hag died on his 79th birthday on April 6. As Keith Richards said, “One of the great country singers of all time and a helluva guitar player. Gonna miss you pal.”

Literary Mountains Climbed: In 2016 I read 31 books totaling almost 12,000 pages. Among them were two that I’ve had on my list for a long time: War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy, and Thomas Wolfe’s Look Homeward, Angel.

Tolstoy’s masterpiece, first published in 1869, is as advertised, one of the best books I’ve ever read. Don’t let its size daunt you: the version I read, Easton Press’s leather-bound edition in its series “The 100 Greatest Books Ever Written,” came in at 1,035 closely written pages. The Count of Monte Cristo and Les Miserables were both longer. It took me 45 days to read, an average of 23 pages a day. That’s easily doable, and most days I read closer to 30-40. It was well worth the time and effort.

Tolstoy’s masterpiece, first published in 1869, is as advertised, one of the best books I’ve ever read. Don’t let its size daunt you: the version I read, Easton Press’s leather-bound edition in its series “The 100 Greatest Books Ever Written,” came in at 1,035 closely written pages. The Count of Monte Cristo and Les Miserables were both longer. It took me 45 days to read, an average of 23 pages a day. That’s easily doable, and most days I read closer to 30-40. It was well worth the time and effort.

For all of its reputation, it’s not hard to read, and the Russian names are not hard to follow. The best advice I can offer is just start reading and keep at it; the names will sort themselves out in good time, and the story will carry you along. Tolstoy is not Dostoyevsky; he doesn’t drill down a thousand feet, he is not concerned with the abstract, the unconscious, or the abnormal. Tolstoy is focused on human life, in all its vastness and complexity, and that’s his real subject in this book. The book drops down into a group of people’s lives and it leaves them still struggling at the end. Along the way, you learn a lot about them, about the choices we all make as human beings—and you’ll learn about yourself as well. As literary critic Clifton Fadiman said so well, “once a few minor hazards are braved, this vast chronicle of Napoleonic times seems to become an open book, as if it had been written in the sunlight.” This is a timeless book with its own rhythm that will have a lasting effect on you long after you finish it, as all great books do. Read it like eating an elephant, one bite at a time. You will not regret it.

Thomas Wolfe’s “young-man-from-the-provinces” theme in his semi-autobiographical Look Homeward, Angel: A Story of the Buried Life (1929) will be familiar to anyone who’s read Stendahl’s classic The Red and the Black. Wolfe of course takes the genre to another level and inspired a host of writers since. I had long imagined Wolfe to be as impenetrable as William Faulkner, but in this I was completely wrong.

Thomas Wolfe’s “young-man-from-the-provinces” theme in his semi-autobiographical Look Homeward, Angel: A Story of the Buried Life (1929) will be familiar to anyone who’s read Stendahl’s classic The Red and the Black. Wolfe of course takes the genre to another level and inspired a host of writers since. I had long imagined Wolfe to be as impenetrable as William Faulkner, but in this I was completely wrong.

After reading A. Scott Berg’s Max Perkins: Editor of Genius, Berg’s award-winning biography of the legendary Scribner’s editor who tamed and cut Wolfe’s rambling prose down to size, I decided to tackle the novel and see for myself. Wolfe’s telling of Eugene Gant’s growing up to age 19 in Altamont, North Carolina, is a tour-de-force: ““By God, I shall spend the rest of my life getting my heart back, healing and forgetting every scar you put upon me when I was a child. The first move I ever made, after the cradle, was to crawl for the door, and every move I have made since has been an effort to escape.” The Gant family was, to put it mildly, dysfunctional before that word became stylish, and Wolfe spares no one. His real hometown of Asheville turned harshly on him when the novel was released because of his unsparing portrait, but he remains North Carolina’s most famous author. The first thing I did after I finished was to order the sequels: Of Time and the River, The Web and the Rock, and You Can’t Go Home Again, the latter two published after Wolfe’s untimely death at 37 in 1938.

Wolfe’s literary star has fallen since his death, unlike those of contemporaries Faulkner, Hemingway, and F. Scott Fitzgerald. In my uninformed opinion he towers over them all, and his books deserve to be more widely read. The title of this essay is perhaps the most famous passage from Wolfe’s first novel and the title he preferred for it. It was for good reason that critic Malcolm Cowley wrote that Wolfe was “the only contemporary writer who can be mentioned in the same breath as Dickens and Dostoevsky.”

Other Mountains Climbed in 2016: Last year in my end-of-year column I wrote that some of my 2016 goals were: “Exercise more. Run more. Read more. Write more. Listen more. Hike more. Bike more. Talk less. Eat less. Complain less. Argue less. Get angry less. Watch TV less. To pick up the phone and talk to someone I haven’t talked to in a long time. To renew friendships and make new ones. To try on a daily basis, as Thomas Jefferson so eloquently put it, to take life by the smooth handle. To meet life and its challenges and opportunities with stoicism. To try, as Marcus Aurelius said, to arise each morning and remember what a precious privilege it is to be alive.”

I succeeded in some areas (I exercised 316 days last year) and not so much in others. The list seems pretty good as I read over it again, so I’ll stick with it for this year. Whatever your goals and aspirations, I hope you succeeded in 2016.

To one and all who took the time to read a word of this blog last year—or any year—I offer my heartfelt thanks. Happy New Year, and I hope to see more of you here in 2017.

The Roar of the Approaching Night

A recent story on the national park at the site of the crash of Flight 93 in Shanksville, Pennsylvania, brought back all the raw emotions of September 11. The anger, the terror, and the realization that our lives can change in an instant was never more starkly on display than on that sun-lit Tuesday fifteen years ago.

A recent story on the national park at the site of the crash of Flight 93 in Shanksville, Pennsylvania, brought back all the raw emotions of September 11. The anger, the terror, and the realization that our lives can change in an instant was never more starkly on display than on that sun-lit Tuesday fifteen years ago.

There will be many moments of reflection on this momentous anniversary. As we do, we should reflect on two other events from this past July that went by virtually unnoticed.

July 1 marked the 100th anniversary of the beginning of the Battle of the Somme during World War I. On July 2, Elie Wiesel died at age 87, the Auschwitz survivor who spoke eloquently for those 6 million who could no longer speak for themselves.

What will happen when those who give voice to hell in the flesh are gone?

At the anniversary of September 11, it’s worth remembering that every event in history that evoked raw emotions was in time smoothed over and faded from memory. In our own time, the Somme and Wiesel’s death should remind us what can happen when the voices of resentment become dominant.

We’ve already forgotten about the horrors of the Somme—and World War I in general. Probably not one American on the street could tell you what happened in that murderous and savage battle. Or at Passchendaele or Verdun.

not one American on the street could tell you what happened in that murderous and savage battle. Or at Passchendaele or Verdun.

The Somme is a river in northern France, and the battle that took place there for 136 days in 1916 has become a metaphor for the useless slaughter of human life.

The Germans were securely entrenched and strategically located when the allied British and French forces launched their frontal attack on a 21-mile front north of the River. Before they sent the men over the top, they shelled the dug-in Germans with a week-long artillery bombardment. For the Germans living through it, it was hell: A soldier who suffered through the bombardment at Verdun said that by day nine almost every soldier was crying. The bombardment was so loud and so intense it could be heard north of London. When the shells subsided for an instant, the air was filled with the buzzing of millions of flies who were eating the dead, and the terrifying high-pitched screams of the rats who often grew so big and bloated from feeding on the dead, it was said that they would attack and eat a wounded man if he couldn’t defend himself. It brought catatonic depression, shell shock, madness.

Saturday, July 1, 1916, was the day of the biggest military fiasco in British history. At 7:30 that morning Field Marshal Douglas Haig, the commander of the British Expeditionary Force, ordered his men over the top, out of their trenches, to attack the German lines head on at the Somme. Within a matter of hours 21,000 British soldiers were killed, 40,000 wounded, many of them within sight of their own trenches.

By noon 60,000 men lay wounded, dying, or dead. Let that soak in. 60,000. The Germans said they didn’t even have to aim, just shoot. The 1st Newfoundland Battalion lost 91% of its men within 40 minutes, which is why July 1 is Memorial Day in Newfoundland and Labrador.

By noon 60,000 men lay wounded, dying, or dead. Let that soak in. 60,000. The Germans said they didn’t even have to aim, just shoot. The 1st Newfoundland Battalion lost 91% of its men within 40 minutes, which is why July 1 is Memorial Day in Newfoundland and Labrador.

After that day, the Somme offensive deteriorated into a battle of attrition. In October torrential rains turned the battlefield into an impassable sea of mud, and by mid-November the Allies had advanced only 5 miles.

Between July and November 1916, there were an estimated 1.3 million Allied and German casualties on the Somme. Among the British losses 73,412 were never recovered or identified.

Let me repeat those figures: 1.3. million casualties in that one battle in a war that lasted over four years. Almost 75,000 missing. To give you some perspective, as of March 23, 2016, the total of those missing in action in Vietnam is 1,621.

All those deaths and mangled bodies, for what? A few yards of mud. Almost no one today can tell you anything about it, or explain how the war began in a toxic brew of ethnic hatred, religious animosities, and tribalistic territorial alliances.

The poison of the first world war culminated of course in the second one.

In 1956, Elie Wiesel published Night, his memoirs of his experience in the concentration camps: “Never shall I forget that night, the first night in camp, which has turned my life into one long night. Never shall I forget that smoke. Never shall I forget the little faces of the children, whose bodies I saw turned into wreaths of smoke beneath a silent blue sky. Never shall I forget these things, even if I am condemned to live as long as God himself. Never.”

In 1956, Elie Wiesel published Night, his memoirs of his experience in the concentration camps: “Never shall I forget that night, the first night in camp, which has turned my life into one long night. Never shall I forget that smoke. Never shall I forget the little faces of the children, whose bodies I saw turned into wreaths of smoke beneath a silent blue sky. Never shall I forget these things, even if I am condemned to live as long as God himself. Never.”

Wiesel recounted it all, including the murders of his father, mother, and sister.

The U.S. Third Army liberated Buchenwald on April 11, 1945. Among the survivors was Elie Wiesel.

“I must do something with my life,” he said years later. “It is too serious to play games with anymore, because in my place, someone else could have been saved. And so I speak for that person.”

The Somme and the Holocaust stand as warnings as we once again find ourselves grappling both at home and around the world with tribalism, revanchism, and nativism. We delude ourselves if we think these things cannot happen again.

The European Union has presided over peace in Europe for the longest period in its history, 71 years and counting, and it is imploding before our eyes in a swirl of economic unrest and ethnic hostility. We think that we are too superior to blunder blindly into another useless and forgotten conflict like World War I, leaving 37 million causalities behind. We are not.

We think we would never allow something like the Holocaust to happen again, that we would see the madmen coming and cut them down before they turned the world into a charnel house again. Would we? Emotions flamed by legitimate fears of terrorism and fueled by religious and ethnic hatred raise troubling doubts.

We think we would never allow something like the Holocaust to happen again, that we would see the madmen coming and cut them down before they turned the world into a charnel house again. Would we? Emotions flamed by legitimate fears of terrorism and fueled by religious and ethnic hatred raise troubling doubts.

This September 11, along with the memory of our dead and the brave warriors who have since died fighting, remember too the dead of the Somme and the unchecked madness that allowed 6 million to be exterminated. The cult of resentment and fanaticism have their fatal and tragic consequences. Night may come again. If it does, humanity itself will be its author—and its final victim.

Elie Wiesel warned that “if we forget, we are guilty, we are accomplices.” 37 million casualties in World War I. Over 100 million in World War II. 6 million human beings in the Holocaust. Fifteen years after September 11 and every day forward, remember.

Elie Wiesel warned that “if we forget, we are guilty, we are accomplices.” 37 million casualties in World War I. Over 100 million in World War II. 6 million human beings in the Holocaust. Fifteen years after September 11 and every day forward, remember.

Remember.