Part 2 of Stan’s interview with historian John Ferling on Jefferson, Paine, and Monroe, as well a lightning round of “Rate that Founding Father.”

Category Archives: Books

S2 E1: The American Revolution and John Ferling, Part 1, October 5, 2018

Stan talks to author John Ferling about his new book, Apostles of Revolution: Jefferson, Paine, Monroe and the Struggle Against the Old Order in America and Europe.

What I’m Reading Now: September 4, 2018

No Irish Exit, Just a Temporary Farewell

No Irish Exit, Just a Temporary Farewell

Last November, I attended a GHS historical marker dedication for former Savannah mayor Malcolm Maclean and afterwards an attendee approached and pulled me aside. Could she kindly make a suggestion? Of course, I replied, bracing for what might be next.

To my surprise, her suggestion was about my blog. Being somewhat technologically challenged, as she put it, she requested more written content and less of my podcast. Podcasts were all well and good, but she missed the essays about history and books and hoped that I’d get back to those.

I thought about her request when I started this column nearly six months ago, intending to see if I could meet the demands of a weekly deadline while at the same time having fun writing about whatever I was reading. The idea came last spring while perusing through back issues of the Saturday Review of Literature, the venerable weekly that was published between 1924 and 1971 that carried a similar essay.

My goal was to keep it short—less than 500 words—and to devote no more than an hour to writing it every week. Alas, I almost always exceeded the word limit and sometimes felt like the preacher Abraham Lincoln famously told a story about. He could have written shorter sermons, the parson confessed, but once he started writing he was too lazy to stop. The truth is, despite what you may believe, it’s much harder and takes more discipline to write 500 words about something you’re interested in than it is to write 1,000. But since I set the rules for this blog, I saw no problem in occasionally breaking them. You, dear reader, were the one who had to pay the price. I also usually spent more than the allotted time, but it was always and always fun.

Why, you ask, am I telling you all of this? This marks my 25th offering over nearly six months, and with this entry, “What I’m Reading Now” will go on a temporary sabbatical to make way for the second season of Off the Deaton Path podcasts. This will no doubt be a great relief to many long-suffering readers who will be spared this weekly agony, while horrifying others who dread the prospect of hearing my voice. Just remember, you’ve been warned.

My other goal here was to see if I could pass along even a fraction of the great passion I have for the printed word and the singular joy that comes from reading a good book. If I’ve succeeded in doing either of those things—even for just one person—then mission accomplished. We’ll lift a glass and declare victory. To quote my old friend Mr. Pickwick: “If I have done but little good, I trust I have done less harm.”

I hope the column will appear intermittently over the next six months as time and other duties allow. To everyone who took a moment to read a few words or who provided feedback, I hope you’ll stay for the podcast and come back for more next spring.

To one and all, a heartfelt and sincere Thank You.

What I’m Reading Now: August 21, 1018

John Ferling, Apostles of Revolution: Jefferson, Paine, Monroe, and the Struggle Against the Old Order in America and Europe (Bloomsbury, 2018, 478 pp.)

John Ferling, Apostles of Revolution: Jefferson, Paine, Monroe, and the Struggle Against the Old Order in America and Europe (Bloomsbury, 2018, 478 pp.)

Among historians writing about the era of the American Revolution, David McCullough, Joseph J. Ellis, Gordon Wood, and Ron Chernow have received the lion’s share of attention in the public arena over the last 20 years. None has been as prolific as John Ferling, however, and none, with the possible exception of Wood, has written for a popular audience with more scholarly erudition.

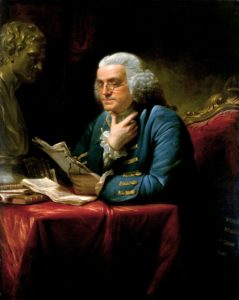

I first met John Ferling in 2000 when he was still teaching full time at what is now the University of West Georgia in Carrollton. He came to Savannah to speak at the Georgia Historical Society about his new book, Setting the World Ablaze: Washington, Adams, Jefferson, and the American Revolution (Oxford University Press), a prosopography of those three Revolutionary stalwarts. Despite teaching full-time, John had already written acclaimed biographies of Washington and Adams, as well as four other books on Early America.

After our first meeting in 2000, John would go on to write eight more books on the Revolutionary era over the next 18 years: A Leap in the Dark: The Struggle to Create the American Republic (Oxford, 2003); Adams vs. Jefferson: The Tumultuous Election of 1800 (Oxford, 2004, a volume in the “Pivotal Moments in American History” series); Almost a Miracle: The American Victory in the War of Independence (Oxford, 2007); The Ascent of George Washington: The Hidden Political Genius of an American Icon (Bloomsbury, 2009); Independence: The Struggle to Set America Free (Bloomsbury, 2011); Jefferson and Hamilton: The Rivalry That Forged a Nation (Bloomsbury, 2013); Whirlwind: The American Revolution and the War That Won It (Bloomsbury, 2015), and his latest.

I’ve written elsewhere on this blog about John’s ability to plow the same ground without saying the same thing. His latest entry remarkably achieves the same goal in that this is the fourth book he’s written with Jefferson’s name in the title, yet he still has new things to say about him. Here Jefferson is foremost among three “apostles of revolution” who sought real and radical changes in the political, social, and economic structure of America and Europe in the last decades of the 18th century and early years of the next.

Thomas Paine to my mind is the most fascinating of the three but also the one whose inner life is most difficult to penetrate. Despite being the subject of several biographies, he is still a somewhat shadowy figure who remains on the historical margins. Paine was something—to use a word from our own day—of a slacker. He never kept gainful employment for very long, and he moved frequently between cities and countries. He is best known, of course, for his writing, and some of it still has the power to electrify. A couple of years ago I read his Age of Reason, an open attack on revealed religion and came away amazed at his intellectual bravery. It would take guts to write that book now, much less in 1795.

Monroe is the most problematic member of this book’s triumvirate, both in terms of his historical and intellectual heft. He’s always seemed something of a lightweight when compared to his historical contemporaries. Ferling certainly gives him a well-deserved spotlight, but the jury is still out on whether he has elevated Monroe’s stature among the leaders of Revolutionary word and deed in the Early Republic. It brings to mind something I read recently about Irving Brant, the author of a monumental 6-volume biography of James Madison, published between 1941 and 1961. Brant wanted to prove that Madison had been unfairly overlooked as one of the mainline founders. When the project was completed, reviewers gave it high praise for its thoroughness, but one critic said that it was so thorough that, instead of rescuing Madison from the Founding B-team, Brant had inadvertently proven that Madison was in fact quite rightly at home among the second-tier.

This caveat aside, John Ferling has once again given those of us who can’t get enough of the original “Greatest Generation” another literary feast—and this won’t be his last. I have it on good authority that he’s already written the first draft of his next book.

Is it too early to pre-order?

What I’m Reading Now: August 14, 2018

John Steinbeck, Travels with Charley: In Search of America (1962, Penguin Books, 277 pp.)

John Steinbeck, Travels with Charley: In Search of America (1962, Penguin Books, 277 pp.)

John Steinbeck is considered to be one of the foremost authors of the 20th century, keeping company with Hemingway, Faulkner, and Fitzgerald. Most of us make our first (and perhaps only) contact with Steinbeck in Of Mice and Men (1937) in high school, or in The Grapes of Wrath (1939), for which he won the 1940 Pulitzer Prize for fiction.

In 1962 he won the Nobel Prize for literature, though many thought his best work was decades behind him. He died in New York five days before Christmas in 1968, nearly 50 years ago, at age 66.

Long before “On the Road” with Charles Kuralt, and three years following Jack Kerouac’s novel of the same name, Steinbeck set out in the fall of 1960 to re-connect with America and its people. Having lived and worked for so long in New York, he felt he’d lost touch with “real” Americans.

In order to travel anonymously as much as possible so that people would talk freely with him, Steinbeck bought a three-quarter-ton pickup truck, had a camper built for its bed, christened it “Rocinante” after Don Quixote’s famous steed, and set out on the highway with his French poodle Charley on a trek that took him from Maine to California. The camper kept him from signing hotel registers, and he claims never to have been recognized by sight.

Along the way he met and talked with ordinary people, slept in Rocinante under the stars and found that the America of his youth and that he had always believed in was still out there. He visited New Hampshire farmers and Yellowstone National Park, always with Charley as his faithful companion: “It is my experience that in some areas Charley is more intelligent than I am, but in others he is abysmally ignorant. He can’t read, can’t drive a car, and has no grasp of mathematics. But in his own field of endeavor, the slow, imperial smelling over and anointing of an area, he has no peer. Of course his horizons are limited, but how wide are mine?”

He published the results in 1962 as a work of non-fiction, and critics raved that it was his best work in years. It’s great fun to read, and you can still see the truck and Rocinante at the National Steinbeck Center in Salinas, California.

But is it really non-fiction? A few years ago a dedicated researcher uncovered that most of it wasn’t, that Steinbeck slept many nights not in Rocinante but in luxury hotels, that the characters and dialogue were largely fiction, and that not only Charley but also his wife Elaine accompanied him much of the way.

This may all be true, but I’m not sure it really matters. What Steinbeck describes—and what he claims that he found universally among the people he met along the way—is a longing and a desire to get away from where we are, to go elsewhere, to be somewhere, anywhere, rather than where we are. “They spoke quietly of how they wanted to go someday, to move about, free and unanchored, not toward something but away from something.”

That still seems as true now—for us an individuals and maybe for the country as a whole—as when Steinbeck wrote it nearly 60 years ago. Even as I read, I fell into the trap of thinking that the early 1960s seemed preferable to the times in which we live, that Steinbeck’s America wasn’t filled with hyper-wired know-it-alls who are divided hopelessly into partisan tribes.

But of course I know better. The past always looks seductively more understandable and simple than our own times, just as another geographic space seems to offer more or less, depending on what you want, than where we stand now.

Travels with Charley—be it fiction or non-fiction—confirms that humans as individuals and as nations are universally restless and unsatisfied, that we always want to go someplace else—in time and/or space—that promises either to bring something back that’s missing or to offer a more fulfilling life than the one we live now. Isn’t this why I play the lottery every week?

As Steinbeck wrote and acknowledged himself, “our capacity for self-delusion is boundless.”