For Independence Day, Stan talks about This Week in History (including Elvis, the CDC, the Beatles, Sherlock Holmes, Thomas Jefferson & John Adams), notes the birthday of a celebrated historian, remembers a segregationist southern governor from the Civil Rights Movement, highlights new additions to the Off the Deaton Path bookshelf, and revisits one of his favorite movies about the American Revolution and the Founding Fathers.

Category Archives: Books

The Indefatigable Dr. Ferling

John Ferling, Winning Independence: The Decisive Years of the Revolutionary War, 1778-1781 (Bloomsbury, 2021, 701 pp., $40)

John Ferling, professor emeritus of history at the University of West Georgia, is one of the most prolific historians writing today—and one of the best. This is John’s 15th book on the colonial and Revolutionary period, and his 10th in the last 21 years. This volume, covering the last three years of the American Revolutionary War, weighs in at 561 pages of text and nearly 150 pages of notes and bibliography.

Long-suffering readers and listeners of Off the Deaton Path know that John and his work have been featured no less three times before, including a two-part interview.

By my count, this is John’s third book that focuses on the military phase of the Revolution, following Almost a Miracle: The American Victory in the War of Independence (Oxford, 2007), and Whirlwind: The American Revolution and the War That Won It (Bloomsbury, 2015). Of course his biographies of George Washington and John Adams cover the war years as well, as does his political history of the war, A Leap in the Dark: The Struggle to Create the American Republic (Oxford, 2003), and his prosopography, Setting the World Ablaze: Washington, Adams, Jefferson, and the American Revolution (Oxford, 2000). Yet he never repeats himself, always offering fresh insights and interpretations.

How does he manage to do this? Here’s what I wrote in a review of his dual biography, Jefferson and Hamilton: The Rivalry That Forged a Nation (Bloomsbury, 2013): “How, one might ask, does Ferling keep plowing the same ground and still have something new to say? Part of it is simply attributable to his maturity as a scholar. Unlike others who leap from one time period to another with each book, Ferling has spent his entire professional life laboring in the vineyard of the Founding era. Ferling isn’t just dabbling in this period; he knows it as well as anyone can who is now two centuries removed from the time about which he’s writing. He is well versed in what the Founders wrote, what they read, what they believed, and what they hoped to achieve. But he’s not awe-struck by them. Simultaneously, his reflections on people and events have deepened with the years, as he himself has aged. As should happen as we grow older, his own insights about human nature reflect his growth as a human being; he’s more empathetic, more forgiving of human foibles and less harsh on their failures, though he isn’t afraid to point them out and to hold men and women accountable for not only what they achieve, but what they fail to achieve. He knows what it’s like to live life, make mistakes, and have regrets. It’s the primary reason why people in their 20s shouldn’t write biographies.”

Rick Atkinson, the author of The British Are Coming: The War for America, 1775-1777 (Henry Holt, 2019), the first volume of his Revolutionary Trilogy, recently told me that he believes some subjects are bottomless. No matter how much is written about some historical periods and people, historians hundreds of years from now will still be producing books on Abraham Lincoln, the Second World War, and the American Revolution.

John Ferling’s masterful prose, in this and all his books, bears this out. As prolific as John is, I have no doubt that other volumes will follow, all exquisitely written, exhaustively researched, and deeply analytical.

Americans are endlessly fascinated by those who fought and won the Revolution, and that first greatest generation has no finer historian than the indefatigable Dr. John Ferling.

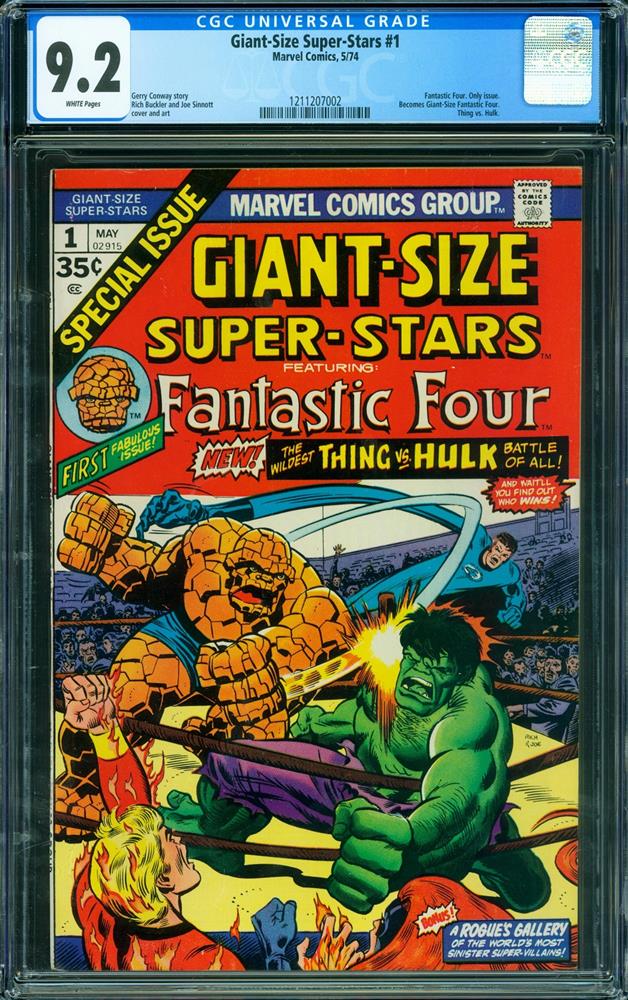

Podcast S4E7: Item! Stan Lee and the Golden Age of Comics

Stan talks about This Week in History (including King George III, AIDS, RFK, Mount Everest, & Charles Dickens), remembers a record-breaking baseball player, highlights new additions to the Off the Deaton Path bookshelf, and spotlights an incredible and historic collection of golden-age comic books about to hit the auction block–and the influence of comics in his own life.

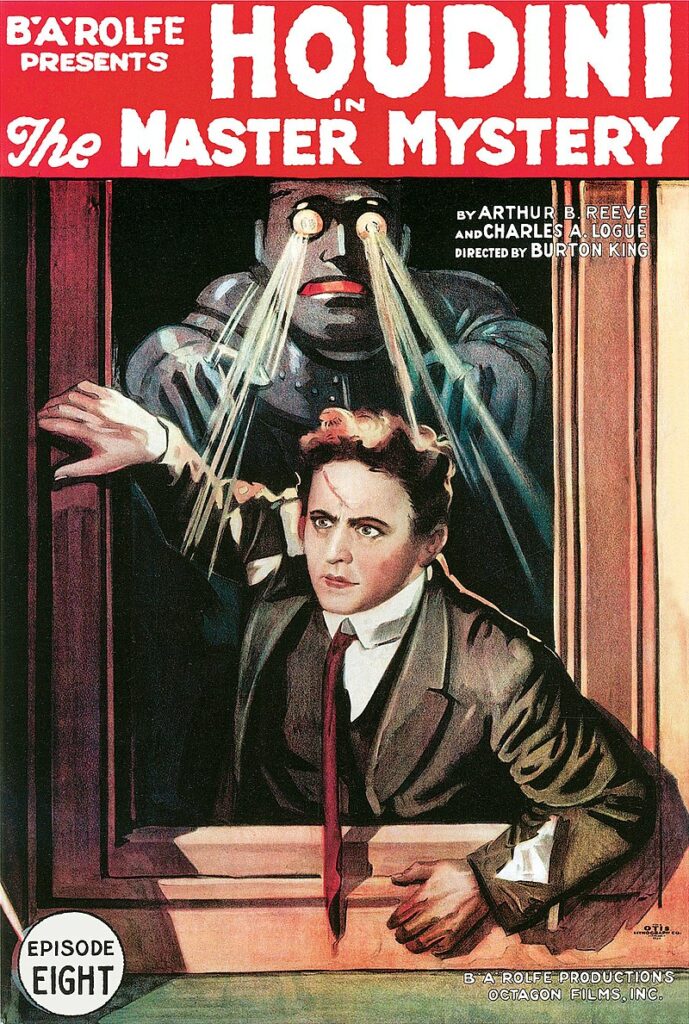

Podcast S4E6: The Stamp Act, Houdini, & Spike Lee

Stan talks about This Week in History (the Stamp Act, James Jackson, Spike Lee, the first Black graduate of West Point, the Masters, Tomochichi, & Houdini), says goodbye to a pathbreaking historian and actor, spotlights new additions to the Off the Deaton Path bookshelf, and welcomes the opening of Major League Baseball.

Q&A: Reading and Writing with Drew Swanson

Drew Swanson is Professor of History at Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio, where he teaches classes in environmental history, food, 19th-century America, and public history. He received his Ph.D. in History from the University of Georgia in 2010. Born in rural Virginia, he worked as a farmer, zookeeper, and natural resource manager before turning to academia. Dr. Swanson’s research examines the intersections of nature and culture in the American South. He is the author of three books: Beyond the Mountains: Commodifying Appalachian Environments (University of Georgia Press, 2018); A Golden Weed: Tobacco and Environment in the Piedmont South (Yale University Press, 2014); and Remaking Wormsloe Plantation: The Environmental History of a Lowcountry Landscape (University of Georgia Press, 2012), which won the Georgia Historical Society’s Malcolm Bell, Jr. and Muriel Barrow Bell Award for the best book in Georgia history in 2013. Dr. Swanson also won the inaugural John C. Inscoe Award in 2017 for the best article published in the Georgia Historical Quarterly the previous year. He currently serves on the GHQ Board of Editors.

What first got you interested in history?

Biology, strangely enough. I majored in biology in college and was working as a naturalist in western North Carolina, and in that job I discovered that the human history of the region fascinated me at least as much as its natural history. When people would point to a tree and ask me what species it was, I would find myself rambling on about how people used to use its bark to dye leather. That realization propelled me back to graduate school and the study of history. I ended up an environmental historian, which fused the two interests.

What kind of reader were you as a child? Which childhood books and authors stick with you most?

I got in trouble in school in the second grade. Once I finished my work I started talking and disturbing others. My teacher began requiring my parents to send me to school with a book that I could read once I completed my assignments, and that got me hooked on the Hardy Boys. From there I turned to science fiction–Isaac Asimov, Orson Scott Card, Ursula K. Le Guin–and then westerns. There’s still a set of the complete works of Zane Grey somewhere in our barn, I’m pretty sure.

And I was voracious, reading at every available moment. I know I looked like the typical sullen tween, with my head down all the time, but it was usually because there was a book hidden under the edge of the desk or table.

What book did you read in grad school that you never want to see again—and what book was most influential?

This is tough. I’ve got a couple of shelves in my office full of books I never intend to read again! Jacques Derrida is probably brilliant, I’m just not quite smart enough to be certain why.

There were plenty of books to love, though. Two that I regularly return to are Brian Donahue’s The Great Meadow: Farmers and the Land in Colonial Concord (Yale University Press, 2007),and Michael Wayne’s Death of an Overseer: Reopening a Murder Investigation from the Plantation South (Oxford University Press, 2001). Donahue is a brilliant example of how crucial it is to really get to know a place in order to better explain its past, and Wayne’s book reminds me of the value of curiosity and good story telling. The past is a mystery, and we shouldn’t downplay that.

What’s the last great book you read, fiction or non-fiction?

I read John Kennedy Toole’s A Confederacy of Dunces (LSU Press, 1980)again not too long ago. It always pulls me in, although it is hard to put a finger on exactly why. If I had to guess, I’d say it is the way his caricatures remind me of real people more than most of the “realistic” fiction out there. It’s hard to exaggerate just how quirky humanity is.

For nonfiction, I thoroughly enjoyed Stephen Heyman’s new biography of Louis Bromfield, The Planter of Modern Life: Louis Bromfield and the Seeds of a Food Revolution (Norton, 2020). Partying with Gertrude Stein and Ernest Hemingway in France, hanging around Hollywood with Humphrey Bogart, experimenting with local food and agricultural improvement on his Ohio farm, and, oh yeah, writing some of the most popular novels of the early twentieth century: Bromfield’s life is almost too bizarre to believe, and Heyman tells it well.

When you’re not reading for your particular field of history, what else do you like to read? What genres do you avoid? And what’s your guilty reading pleasure?

I love how-to manuals. Masonry, carpentry, small engine repair, plans for building garden sheds, cookbooks, and the like. I think it’s a form of procrastination—I can read about doing these things rather than actually get up and accomplish something.

I avoid poetry. It has never made sense to me. (My dad’s a poet, so there may be something psychological involved here.) I deal with 19th-century sources in my work, and it was an age in love with poetry. Every time I strike a poem in a source I’m reading I groan a little inside.

As far as guilty reads go, I love a good detective procedural. The more atmospheric European serials tend to hook me, like the work of John Harvey, Henning Mankell, Tana French, and and Arnaldur Indridason.

What do you read—in print or online—to stay informed?

I’ve tried to cut down on my news consumption in recent months. The danger of being uninformed seems less than the hazard of being overwhelmed. It’s a trade off, to be sure, but I’m attempting to focus more on what’s going on in my local community. We still get a local newspaper, the quirky but excellent Yellow Springs News (independently owned since 1880!), which is chock full of village shenanigans, combative editorials, and actual locally relevant news stories. Not to mention an infamous weekly police blotter.

Describe your ideal reading experience (when, where, what, how).

Nodding off in the evening to one of those aforementioned detective novels.

What’s your favorite book no one else has heard of?

It would be a stretch to describe it as unknown, but I love Wendell Berry’s essay collection, Home Economics: Fourteen Essays (North Point, 1987). In his unification of home and work life, philosophy and practicality, Berry appeals to me. This collection tends to be overshadowed by The Unsettling of America: Culture and Agriculture (Sierra Club, 1977) and The Gift of Good Land: Further Essays Cultural and Agricultural (North Point, 1981), but in my mind it is one of his best. And damn, can he write. There’s a power and grace in Berry’s language that I’d love to emulate, but I can’t.

What book or collection of books might people be surprised to find on your shelves?

I have a lot of field guides left over from my previous work. If you want to identify a mushroom you found in the Pacific Northwest or skim through the Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas, I have you covered.

How have your reading tastes changed over time?

I have less patience for the sort of jargon I could stomach in graduate school. I’ll stop reading a book that I should probably finish if it is unnecessarily dense. The linguistic gymnastics that once impressed me as signs of insight now just make me wish for a well-told story. Historians lament that general readers so rarely find and read our work, but we’re not doing as much as we could to help them out.

Disappointing, overrated, just not good: What book did you feel as if you were supposed to like, and didn’t? Do you remember the last book you put down without finishing?

Salmon Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses (Viking, 1989). It seems obligatory, and I’ve been trying to read it for more than ten years. I start it and then always lose the thread.

What book would you recommend for America’s current moment?

It never hurts to read more Flannery O’Connor. She had a remarkable talent for tackling tough, divisive issues in an empathetic way. Race, religion, sex, disability—she wrote about it all in a way that still seems fresh and moving.

I’m also a huge fan of Tiya Miles’s Tales from the Haunted South: Dark Tourism and Memories of Slavery from the Civil War Era (University of North Carolina Press, 2015). It’s a powerful dive into what titillates us about the southern past, and, as O’Connor observes, the truth isn’t always pretty.

And Jon Ronson’s So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed (Riverhead, 2015). He was a couple of years ahead of the curve on the trouble with cancel culture.

What do you plan to read next?

A lot of agricultural history! I am on a book prize committee for the Agricultural History Society, and a pile of new titles is stacked by my desk. In my reading so far I’ve been really impressed by the excellent recent work in the field. America’s small farmers may be struggling, but historians are doing a great job of explaining how they reached this point.

What is the next book you’re going to write?

A history of the consumer culture of American hunting since the Civil War. There is an irony at the heart of the project: We like to think we go to the woods to “get away from it all,” but we sure take a lot of stuff with us. I’ve found a pretty fascinating group of characters who helped create this trend, the sort of people we might today be tempted to call “influencers.” I won’t give away too much, but they include an alcoholic ex-librarian holed up in the Great Smoky Mountains, bow hunters chasing lions in Tanzania in Ford Model-T’s, and Ted Nugent. I’m having fun with the process.

When and how do you write?

I do all the things I tell my students not to do: I write in short bursts, I write in the bleachers at my kids’ swim practices, I write with the television on in the background, sometimes I write after I’ve had a beer. It’s a matter of necessity more than preference, but I’ve also discovered that my focus seems sharpest in short blocks of time. If I know that I have 45 minutes to write, I will really bear down. Give me a day set aside to do nothing but write, and I’ll end up staring out the window.

For me the most important thing seems to be to get words on paper, to make steady progress. That keeps me from feeling like I’m falling behind on a project. It also means I spend a lot of time revising and editing, and I’m okay with that.

With which three historic figures, dead or alive, would you like to have dinner?

Anthony Bourdain, Alice Waters, and Donald Link. I’m taking the “dinner” part of the question seriously.