Marcel Proust, Swann’s Way: In Search of Lost Time, Volume 1. The C. Scott Moncrieff Translation, Edited and Annotated by William C. Carter (1913; rpt. Yale University Press, 2013, 487 pp.)

“What are you reading these days, Stan?”

“Proust.”

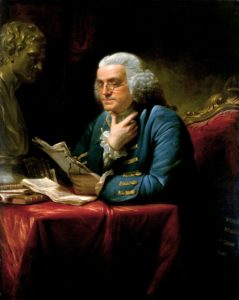

Let’s face it, one of the best reasons for reading an author like Marcel Proust is being able to tell people that you’re reading an author like Marcel Proust. To get the full effect, you should be wearing a bow tie, adjusting your monocle, and holding a pipe.

While I was reading Proust, I had no less than three occasions to tell inquiring minds that I was reading Proust, just as if I’d tee’d it up myself. Even without the bow tie, monocle, or pipe the effect remained the same: the questioner seemed impressed, slightly bemused, or downright baffled by my choice of summer reading. Responses ranged from “Hmm, something heavy,” to “A little light reading, huh?” to “Who?”

My own response might be, “Why?”

The reason, of course, is that Proust is one of those writers, like James Joyce, William Faulkner, and Thomas Wolfe, that usually show up on the list of 20th-century authors who are “must-reads.” But are they really? You began to wonder once you start reading their books. Their writing can seem like trying to climb the literary Mount Everest–forbidding, daunting, and, yes, even unreadable. Who hasn’t cracked open Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury and wondered, what the hell is even going on here?

In Search of Lost Time is made up of not one but seven volumes, of which Swann’s Way is the first. Proust published it at his own expense in 1913; he published two more volumes before his death in 1922 and the last four were published posthumously between 1923 and 1927.

“This is the longest first-rate novel ever written. Its difficulties, like its rewards, are vast. If you respond to it at all (many do not) you may feel quite justified in spending what time you can spare over the next five or ten years making it a part of your interior world.” So wrote Clifton Fadiman in his essay on Proust in The Lifetime Reading Plan nearly 60 years ago. The Encyclopedia Britannica calls it “one of the most profound achievements of the human imagination.” All of this is still true.

What is this book about? In 1909 Proust experienced a moment that perhaps you’ve shared: the involuntary recall of a childhood memory. It happened through the act of eating a piece of bread dipped in tea. Struck by the impact of it, he committed the rest of his life to writing a novel about recapturing lost time, the vanished past that gives our lives beauty and meaning. The novel was formerly referred to as Remembrance of Things Past.

Sometimes it’s heavy sledding, and sometimes not. The prose is famously beautiful, but, as Fadiman says, Proust can analyze “with intolerable exhaustiveness” and you may agree with him and other critics that the book is “less like a narrative than a symphony.” Proust could challenge Henry James for sentences that go on for days, but for all the underbrush, when you do come upon a clearance the views are indeed magnificent.

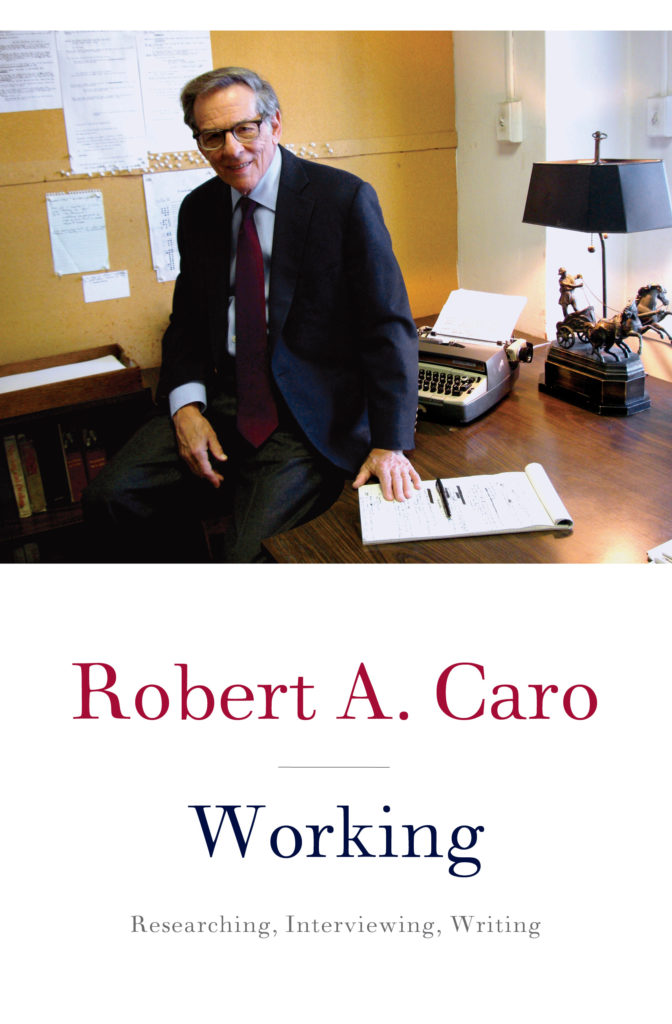

To say that there is a Proust cult would be an understatement. Shelby Foote–he of Civil War and Ken Burns fame–read all seven volumes at least nine times in his life and considered him second only to Shakespeare among writers. Alan Jacobs in The Pleasure of Reading in the Age of Distraction (Oxford, 2011) wrote that one of his high school teachers affirmed that she read the entire seven volumes every summer “because the book was so great, and so deep, and so subtle that she always found something new in it, always had more to learn about it and through it.” Yale University Press is in the midst of publishing new editions of the C. Scott Moncrieff translation, edited and annotated by the renowned Proust scholar and biographer William C. Carter.

There seem to be three schools of thought on this tome: that it’s the greatest novel in the world; that it’s unreadable; or, finally, that it’s mammoth but minor. To which of these do I subscribe after finishing the first volume?

I did not find it unreadable, though I can definitely say that at times I felt like the proverbial buyer who wanders in but is “just looking around”–I wasn’t always sure what was going on but I admired everything and just kept moving. At this point I wouldn’t call it the greatest novel ever written, but give me another year and I’ll be ready to tackle the next volume.

If Proust really is better than Dickens, Tolstoy, Austen, Hugo, Dumas, or a host of others, he will be a mountain well worth climbing.

Check back with me in about ten years.