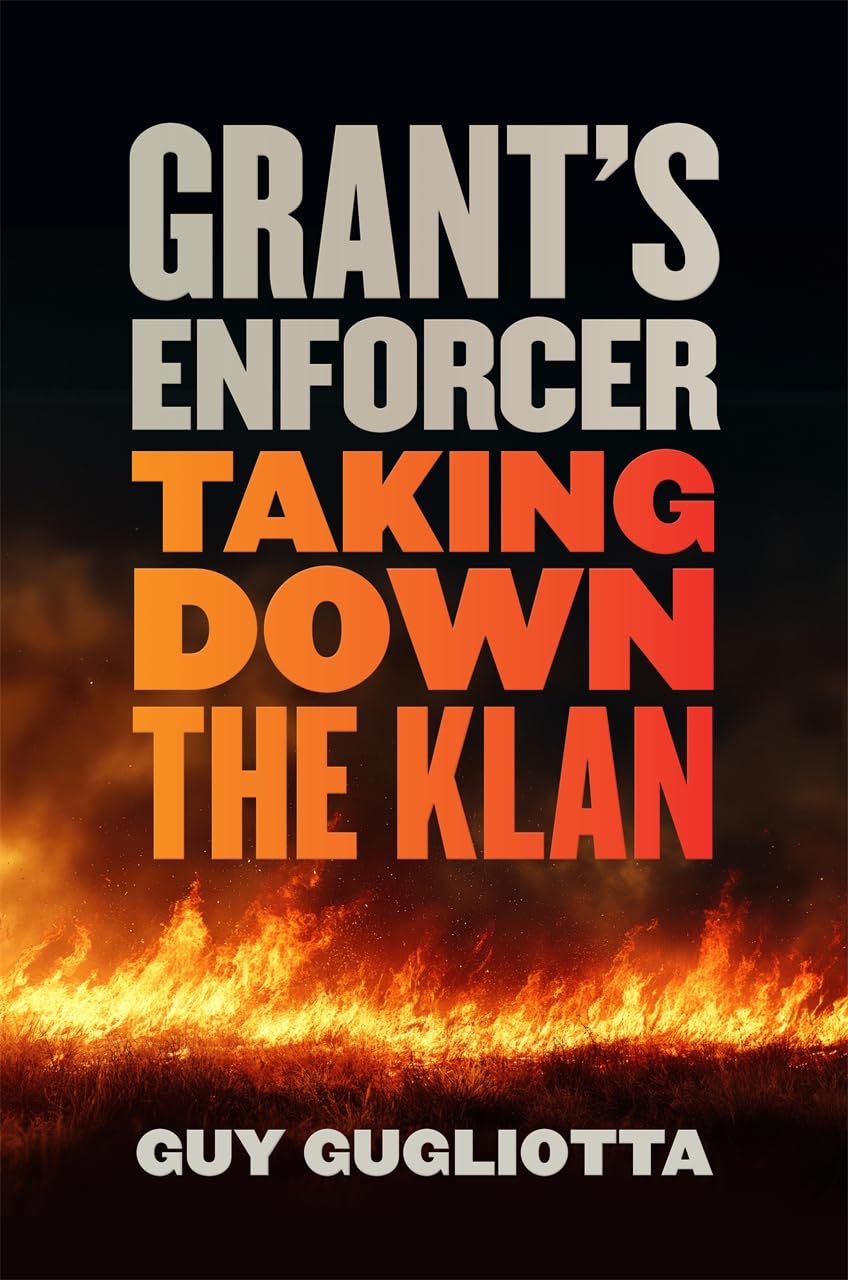

Stan’s guest this week is journalist and author Guy Gugliotta, discussing his new book, Grant’s Enforcer: Taking Down the Klan, published on April 15 of this year by the University of Georgia Press. It’s the story of how Amos T. Akerman, a Georgian, was appointed by President Ulysses S. Grant in 1870 to become the Attorney General of the United States, the first to lead the newly created Department of Justice, and how he waged war against and defeated the Reconstruction-era Ku Klux Klan.

Please note, due to a recording equipment glitch, portions of the audio may sound distorted. Even still, we think you’ll enjoy this conversation!

Version 1.0.0