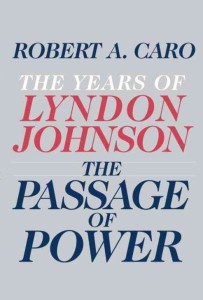

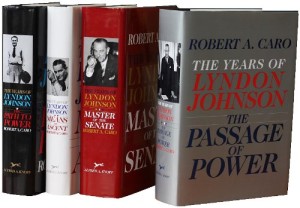

The Passage of Power: The Years of Lyndon Johnson. By Robert Caro. Alfred A. Knopf, 2012, 712 pp., $35.

The Passage of Power: The Years of Lyndon Johnson. By Robert Caro. Alfred A. Knopf, 2012, 712 pp., $35.

The assassination of President John F. Kennedy on November 22, 1963, continues to fascinate fifty years after that horrific Friday in Dallas. With the nation having just commemorated that milestone, I decided it was time to delve into the latest volume of Robert Caro’s massive-and-as-yet-unfinished biography of Lyndon B. Johnson. The Passage of Power covers the years 1958 to early 1964, including the Kennedy assassination and Johnson’s rise to power because of it, and it’s a masterful if wordy account.

In 1988, the nation marked the twenty-fifth anniversary of the tragedy, and CBS broadcast its coverage of the assassination and its aftermath in a 2-hour documentary entitled “Four Days in November 1963: The Assassination of President Kennedy.” Except for the occasional Dan Rather commentary, it was simply a re-broadcast of the coverage as it originally aired from November 22-25, 1963, and it was very powerful. Watching that show marked the first time I ever saw the unedited Abraham Zapruder film, and it shocked me. You can watch the CBS documentary on You Tube.

There have of course been innumerable documentaries on the Kennedy assassination and the conspiracies it has spawned, chief among the latter being Oliver Stone’s problematic film. Highly recommended, at least by me, is Robert Stone’s “Oswald’s Ghost,” originally broadcast in 2007 as an episode of PBS’s highly acclaimed “American Experience” series. There are too many others to mention but easily found—and in most cases watched—in the era of the internet.

Books and articles on the assassination abound too, of course, much of it written by amateur sleuths, would-be scholars, or outright hacks with a conspiracy theory ax to grind. It can be hard for published scholarship to keep up and compete with the overload of motion pictures, TV shows, and internet sites on the subject.

But make no mistake, the best written account of the assassination and its aftermath is here, in the pages of Caro’s fourth volume of his fascinating study.

Robert Caro’s biography is written in the grand style of the old nineteenth- and twentieth-century biographers, who spent decades and thousands of pages detailing the lives of their subjects. Who does this anymore? Dumas Malone spent nearly half a century researching and writing his 6-volume Jefferson and His Time, published in the 38 years between 1943 and 1981. Irving Brant’s 6-volume James Madison was published between 1941 and 1961, while Douglas Southall Freeman cranked out 4 volumes on Robert E. Lee, 3 more on Lee’s Lieutenants, and finished 6 books of a 7-volume biography of George Washington, all of it published in the 17 years between 1936 and Freeman’s death in 1953.

Caro is writing at a comparatively glacial pace. He began work on the LBJ project in 1976; the first volume, The Path to Power, appeared six years later in 1982, and three more volumes have been published in the intervening 30 years, averaging about 10 years between every book. Together the four tomes total about 3,300 pages and weigh more than Chris Christie’s lunch box.

Caro is writing at a comparatively glacial pace. He began work on the LBJ project in 1976; the first volume, The Path to Power, appeared six years later in 1982, and three more volumes have been published in the intervening 30 years, averaging about 10 years between every book. Together the four tomes total about 3,300 pages and weigh more than Chris Christie’s lunch box.

As a friend of mine once joked, all an author has to do to get me to buy a book is to put “Volume 1” on the cover. I’m a sucker for the multi-volume set and a completist at heart. My study is full of them, from all of the ones mentioned above, to the 60-volume Great Books of the Western World series (second edition), and its two companion series: the 10-volume Gateway to the Great Books, and the 38 volumes of The Great Ideas Today (published between 1961 and 1998); the Harvard Classics (51 volumes), Gibbon’s 6-volumes of The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, a complete set of the famous 11th edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica (29 volumes), and all manner of other multi-volume histories and biographies.

As a friend of mine once joked, all an author has to do to get me to buy a book is to put “Volume 1” on the cover. I’m a sucker for the multi-volume set and a completist at heart. My study is full of them, from all of the ones mentioned above, to the 60-volume Great Books of the Western World series (second edition), and its two companion series: the 10-volume Gateway to the Great Books, and the 38 volumes of The Great Ideas Today (published between 1961 and 1998); the Harvard Classics (51 volumes), Gibbon’s 6-volumes of The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, a complete set of the famous 11th edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica (29 volumes), and all manner of other multi-volume histories and biographies.

As multi-volume sets go, Caro’s four volumes on LBJ don’t sound like much, but they take up practically their own shelf. As I said above, they’re weighty tomes with small print—the shortest is 500 pages–but they’re all prize winners. The first two, The Path to Power and Means of Ascent, won the National Book Critics Circle Award, as has the latest volume. The third volume, Master of the Senate, won the Pulitzer Prize in biography and the National Book Award. It’s worth noting that the third installment was almost as long as the first two combined.

The latest volume comes in at 605 pages of text, and half of that covers the 47 days between JFK’s assassination and LBJ’s State of the Union address on January 8, 1964. The events of November 22 get 65 pages all by themselves, and it is riveting text. For Caro, LBJ’s flawless transition to the power of the presidency was his finest hour. Having witnessed so much of Johnson at his worst—the second volume, Means of Ascent, focuses almost entirely on the corrupt 1948 Senate election that LBJ won by 87 votes—Caro believes that the passage of power found the Texan at his best.

The latest volume comes in at 605 pages of text, and half of that covers the 47 days between JFK’s assassination and LBJ’s State of the Union address on January 8, 1964. The events of November 22 get 65 pages all by themselves, and it is riveting text. For Caro, LBJ’s flawless transition to the power of the presidency was his finest hour. Having witnessed so much of Johnson at his worst—the second volume, Means of Ascent, focuses almost entirely on the corrupt 1948 Senate election that LBJ won by 87 votes—Caro believes that the passage of power found the Texan at his best.

One reason the books are so big and so long is that Caro left no stone unturned in his research. He has talked to anyone and everyone associated with Johnson who would in fact talk with him (LBJ’s press secretary Bill Moyers never has). The book is filled to overflowing with insights, anecdotes, and analysis of LBJ and the Kennedy administration that make it hard to put down.

One reason the books are so big and so long is that Caro left no stone unturned in his research. He has talked to anyone and everyone associated with Johnson who would in fact talk with him (LBJ’s press secretary Bill Moyers never has). The book is filled to overflowing with insights, anecdotes, and analysis of LBJ and the Kennedy administration that make it hard to put down.

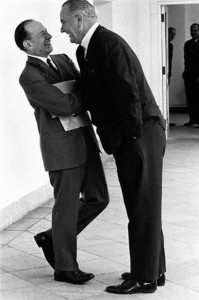

Caro is at his best in describing three things in particular: the Democratic campaign of 1960 in which LBJ’s dithering and failure to fully commit resulting in losing the nomination to JFK; the co mbustible LBJ-Bobby Kennedy relationship and the hatred on both sides; and LBJ’s masterful transition from VP to President in the minutes, hours, and days following Kennedy’s assassination.

mbustible LBJ-Bobby Kennedy relationship and the hatred on both sides; and LBJ’s masterful transition from VP to President in the minutes, hours, and days following Kennedy’s assassination.

Derided by Camelot denizens and journalists alike as Colonel Cornpone or Rufus Cornpone while he was vice president, Johnson assumed power flawlessly and tactfully before ever leaving Parkland Hospital in Dallas. Standing against a back wall in a cubicle in the Parkland Minor Medicine section, LBJ received the news of Kennedy’s death from a heart-broken Kenny O’Donnell: “He’s gone.”

In that moment, everything changed. The powerless vice president immediately became the Lyndon Johnson of old. Insisting on taking the oath of office before leaving Dallas (and offending the Kennedys by doing so), in the next few days he retained key JFK aides, calmed and united the American people behind the new (and un-elected) president, and reassured the world that America would seamlessly continue its leadership in the Cold War.

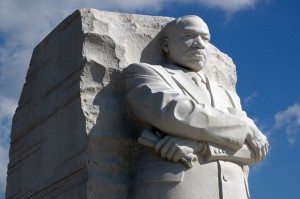

In the 47 days following the assassination, the former Master of the Senate managed–through political savvy, flattery, and invoking the legacy of the martyred Kennedy–to skillfully maneuver key pieces of JFK’s legislative agenda through Congress that had been stalled for three years. The master stroke was getting Kennedy’s Civil Rights bill passed by both houses of Congress later in 1964, overcoming the usual southern intransigence and stonewalling.

“Power is where power goes,” LBJ said, and as president he used it effectively as few other presidents have before or since, as great a combination of restraint and outright political arm-twisting as can be imagined. He wooed the fiscally conservative Harry Byrd relentlessly in passing a tax cut, strong-armed his segregationist mentor Richard Russell into serving on the Warren Commission (Russell hated Earl Warren for Brown v. Board of Education) and coaxed and flattered Robert McNamara, Dean Rusk, and McGeorge Bundy into staying on in the Cabinet after Kennedy’s death. He even persuaded long-time Kennedy stalwart Ted Sorensen that he could best serve JFK’s legacy by writing the speech LBJ delivered to a joint session of Congress just two days after Kennedy’s funeral and the State of the Union address on January 8.

“Power is where power goes,” LBJ said, and as president he used it effectively as few other presidents have before or since, as great a combination of restraint and outright political arm-twisting as can be imagined. He wooed the fiscally conservative Harry Byrd relentlessly in passing a tax cut, strong-armed his segregationist mentor Richard Russell into serving on the Warren Commission (Russell hated Earl Warren for Brown v. Board of Education) and coaxed and flattered Robert McNamara, Dean Rusk, and McGeorge Bundy into staying on in the Cabinet after Kennedy’s death. He even persuaded long-time Kennedy stalwart Ted Sorensen that he could best serve JFK’s legacy by writing the speech LBJ delivered to a joint session of Congress just two days after Kennedy’s funeral and the State of the Union address on January 8.

The seven weeks are for Caro probably the most pivotal in American history. Johnson, Caro writes, used those seven weeks “as a platform from which to launch a crusade for social justice on a vast new scale”—the beginning of LBJ’s historic Civil Rights bills, the war on poverty, Medicare, Medicaid, and the Great Society, all of which transformed the country.

During those seven weeks, Johnson had conquered himself, held the worst of his personality in check—the insecurity, indecisiveness, paranoia, the need to dominate and control—and for Caro it was his finest hour: “In the life of Lyndon Baines Johnson, this period stands out as different from the rest, as perhaps that life’s finest moment, as a moment not only masterful, but, in its way, heroic.”

During those seven weeks, Johnson had conquered himself, held the worst of his personality in check—the insecurity, indecisiveness, paranoia, the need to dominate and control—and for Caro it was his finest hour: “In the life of Lyndon Baines Johnson, this period stands out as different from the rest, as perhaps that life’s finest moment, as a moment not only masterful, but, in its way, heroic.”

The tragedy is that it wouldn’t last. The next (and presumably last) volume will chronicle the spiral downward into the quagmire of the Vietnam War, civil unrest at home, the anti-war movement, the King and RFK assassinations of 1968, and a White House and president increasingly under siege. It all resulted, of course, in a Richard Nixon presidency and eventually Watergate. As Caro points out, the prestige of the presidency would never be the same after those 47 days.

William Manchester didn’t live to finish his 3-volume biography of Winston Churchill. Douglas Southall Freeman’s George Washington was one volume short of the finish line at the time of his death. Robert Caro says that he’s completed the research on the next volume already, that all he needs to do is write it. He’s now 78. One can only hope that his writing pace picks up, because having come this far, it would be a crime if Caro didn’t journey with LBJ all the way to the end. The last line of the last volume, he says, is already written.

William Manchester didn’t live to finish his 3-volume biography of Winston Churchill. Douglas Southall Freeman’s George Washington was one volume short of the finish line at the time of his death. Robert Caro says that he’s completed the research on the next volume already, that all he needs to do is write it. He’s now 78. One can only hope that his writing pace picks up, because having come this far, it would be a crime if Caro didn’t journey with LBJ all the way to the end. The last line of the last volume, he says, is already written.

But if these four volumes are all we get, if the story ends here, it will be more than enough. Caro has already given us a literary monument the likes of which we are not likely to see again.