The news this week that the Atlanta Braves are leaving downtown Atlanta when their lease expires at Turner Field after the end of the 2016 season made me think about the Braves teams I grew up with.

The news this week that the Atlanta Braves are leaving downtown Atlanta when their lease expires at Turner Field after the end of the 2016 season made me think about the Braves teams I grew up with.

Ted Turner may have called them “America’s Team,” but for most of their time in Atlanta before 1991 they were lovable losers. The Braves played their first Atlanta season after moving from Milwaukee in 1966. In 25 years, they made the playoffs twice, in 1969 and again in 1982.

In between, Braves fans witnessed everything from Chief Noc-A-Homa to “Not Too Shabby” while learning to pronounce names like Pocoroba, Messersmith, and Asselstine. There were a few highlights and some great players like Hank Aaron, Phil Niekro, and Dale Murphy, but the Braves lost more games than any other Major League franchise between 1966 and 1990.

In between, Braves fans witnessed everything from Chief Noc-A-Homa to “Not Too Shabby” while learning to pronounce names like Pocoroba, Messersmith, and Asselstine. There were a few highlights and some great players like Hank Aaron, Phil Niekro, and Dale Murphy, but the Braves lost more games than any other Major League franchise between 1966 and 1990.

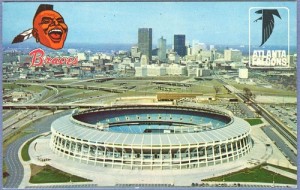

Those teams, of course, played in the old Atlanta Fulton-County Stadium, which was the brainchild of Mayor Ivan Allen, Jr., who promised in his 1961 mayoral campaign to bring major league sports to Atlanta. With financial support from C&S Bank president Mills B. Lane, Jr., they chose a 62-acre site that had been a neighborhood. Since this is a history column, it’s worth  noting that it was the neighborhood where Leo Frank lived when he was working at the National Pencil Factory in 1913 when he was arrested for the murder of Mary Phagan.

noting that it was the neighborhood where Leo Frank lived when he was working at the National Pencil Factory in 1913 when he was arrested for the murder of Mary Phagan.

In February 1964, the city lured the Braves from Milwaukee, city officials broke ground on the new stadium on April 15 of that year, and the “concrete donut,” as critics called Atlanta Stadium, was completed a year later in April 1965 for $18 million.

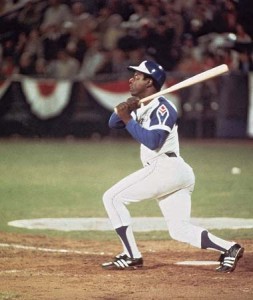

The Braves began play on schedule in 1966. There were bad games, but there were other milestones at the old Stadium as well: the Beatles concert in 1965, the Braves first National League West championship in 1969, Hank Aaron’s record-breaking home run in 1974, the Braves World Series championship in 1995, and Olympic baseball in 1996. The stadium was demolished in 1997 and the site of th e old field is now a Turner Field parking lot.

e old field is now a Turner Field parking lot.

Atlanta Mayor Kasim Reed has said that Turner Field will be torn down when the Braves move. No word yet on whether the outline of the old Atlanta Stadium playing field that now lies in a Turner Field parking lot will be preserved or not. Make no mistake, the site of Hammerin’ Hank’s historic tater in 1974 deserves to be marked and remembered, no matter what happens to the Ted itself after the Bravos head north on I-75.

Atlanta Mayor Kasim Reed has said that Turner Field will be torn down when the Braves move. No word yet on whether the outline of the old Atlanta Stadium playing field that now lies in a Turner Field parking lot will be preserved or not. Make no mistake, the site of Hammerin’ Hank’s historic tater in 1974 deserves to be marked and remembered, no matter what happens to the Ted itself after the Bravos head north on I-75.

My very first Braves game was on Saturday, September 29, 1973,the penultimate game of the ’73 season. I was not yet 9 years old and in fourth grade at W.C. Britt Elementary School in Snellville, then a small bedroom community of Atlanta. My parents took my brother and me to see the Braves play the Astros in hopes that we’d also see history: Hank Aaron was chasing Babe Ruth’s homerun record of 714, and Hank stood at 712 entering play that night. After stopping for supper at Jack’s Corral on Highway 78, we headed down to my first major league baseball game.

We were part of a crowd of 17,836 who showed up that evening, and The Hammer almost did it. We had seats on the upper deck of the third base side, and Aaron hit a long drive off Jerry Reuss down the line in left that just barely missed the foul pole. That would have been 713 but wasn’t by only inches. He actually did hit 713 a few innings later, his 40th of the season, on the way to a 7-0 Braves win behind a complete game shutout by Carl Morton. Hank went 3 for 3, with 3 RBIs, but he came up one dinger short of tying the record that night.

We were part of a crowd of 17,836 who showed up that evening, and The Hammer almost did it. We had seats on the upper deck of the third base side, and Aaron hit a long drive off Jerry Reuss down the line in left that just barely missed the foul pole. That would have been 713 but wasn’t by only inches. He actually did hit 713 a few innings later, his 40th of the season, on the way to a 7-0 Braves win behind a complete game shutout by Carl Morton. Hank went 3 for 3, with 3 RBIs, but he came up one dinger short of tying the record that night.

Hank didn’t hit one the next day either , so Braves fans had to wait till the start of the ’74 season for him to tie the record on opening day, April 4, in Cincinnati. I’ve always thought there should be a place in the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown for my 4th-grade teacher, Mrs. Moon, who turned on our classroom TV that afternoon and allowed us to witness baseball history.

Four days later, Aaron shattered Ruth’s record at home in the Concrete Donut on April 8. It was a 4th inning shot off Al Downing of the Dodgers, and I watched it on TV, a rare local pre-TBS telecast that featured Milo Hamilton on WSB Channel 2 in Atlanta.

After that first game in 1973, it was nearly three years before I attended another game in person, but I was a baseball lifer. I began watching the World Series in 1973, and have seen the deciding game of every Series since.

In 6th grade I made straight A’s (which apparently I did quite frequently in my early scholastic career until the equivalent of a head-on and bloody collision with 9th-grade algebra), and the Braves gave away tickets to three games that season in a “Straight A” ticket program. For all I know they still do this. I remember taking the information home to my Dad, who picked out the teams and games we’d go to. Dad had an eye for the good teams.

First up were the Pittsburgh Pirates on Sunday, June 13, 1976. The Pirates of course had the legendary Willie Stargell at first, and the Candy Man, John Candeleria, started for them on the mound that day, a 6-2 Pirates win.

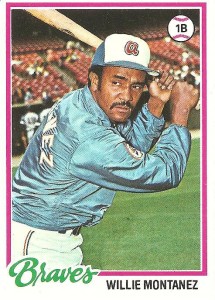

I can still remember the Braves lineup that day, as I watched nearly every game on TBS after this one: Rowland Office, Lee Lacy, Jimmy Wynn (the “Toy Cannon”), Earl Williams, Tom Paciorek, Ken Henderson, Jerry Royster (“Rooster”), Darrel Chaney, and Phil “Knucksie” Niekro on the mound. That day was historic also because it was the day the Braves acquired from the Giants my soon-to-be favorite player, Willie “Hot Dog” Montanez , to play first base. The Braves got him and three other players for Darrell Evans and Marty Perez. Montanez flipped his bat on the way to the plate, wore colorful wrist bands, snatched fly balls out of the sky with his first baseman’s mitt, and repeatedly tagged opposing players who slid back safely into first on steal attempts, much to their annoyance.

I can still remember the Braves lineup that day, as I watched nearly every game on TBS after this one: Rowland Office, Lee Lacy, Jimmy Wynn (the “Toy Cannon”), Earl Williams, Tom Paciorek, Ken Henderson, Jerry Royster (“Rooster”), Darrel Chaney, and Phil “Knucksie” Niekro on the mound. That day was historic also because it was the day the Braves acquired from the Giants my soon-to-be favorite player, Willie “Hot Dog” Montanez , to play first base. The Braves got him and three other players for Darrell Evans and Marty Perez. Montanez flipped his bat on the way to the plate, wore colorful wrist bands, snatched fly balls out of the sky with his first baseman’s mitt, and repeatedly tagged opposing players who slid back safely into first on steal attempts, much to their annoyance.

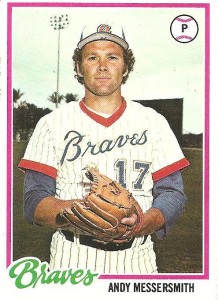

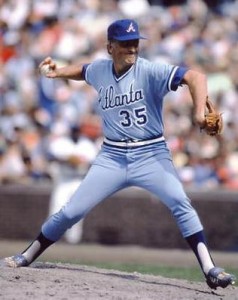

A month later we went to see the Braves play the Big Red Machine, one of the great baseball moments of my life. The Cincinnati Reds had beaten the Red Sox in the previous fall’s World Series and were on their way to a repeat that summer. I saw them in a July doubleheader, and they were all on the field: Pete Rose, Ken Griffey, Joe Morgan, George Foster, Johnny Bench, Tony Perez, Davey Concepcion, and Cesar Geronimo. Andy Messersmith pitched the Braves to a 5-4 win in the opening game, but we lost 6-3 in the nightcap. Hot Dog, however, went 3 for 5, so I was happy. And not one but two games in the same day with the Big Red Machine? What baseball fan wouldn’t be thrilled.

A month later we went to see the Braves play the Big Red Machine, one of the great baseball moments of my life. The Cincinnati Reds had beaten the Red Sox in the previous fall’s World Series and were on their way to a repeat that summer. I saw them in a July doubleheader, and they were all on the field: Pete Rose, Ken Griffey, Joe Morgan, George Foster, Johnny Bench, Tony Perez, Davey Concepcion, and Cesar Geronimo. Andy Messersmith pitched the Braves to a 5-4 win in the opening game, but we lost 6-3 in the nightcap. Hot Dog, however, went 3 for 5, so I was happy. And not one but two games in the same day with the Big Red Machine? What baseball fan wouldn’t be thrilled.

Despite their losing 92 games that season, I stuck with the Braves. The next season, 1977, was among the worst in Braves history. The team lost 101 games, including 17 in a row at in April and May. Things got so bad that season that Ted Turner came down out of the owner’s box and actually managed a game at one point. Commissioner Bowie Kuhn put a stop to that happening again.

To give you some idea of how bad the Braves were, starting pitcher Phil Niekro won 16 games but lost 20 that season, and he would repeat the 20-loss feat two years later by going 21-20. Virtually no manager ever lets a starter lose 20 games in a season anymore. It’s only happened once since 1980 (Mike Maroth with the Tigers in 2003). Knucksie did it twice in three seasons, and he’s in the Hall of Fame.

To give you some idea of how bad the Braves were, starting pitcher Phil Niekro won 16 games but lost 20 that season, and he would repeat the 20-loss feat two years later by going 21-20. Virtually no manager ever lets a starter lose 20 games in a season anymore. It’s only happened once since 1980 (Mike Maroth with the Tigers in 2003). Knucksie did it twice in three seasons, and he’s in the Hall of Fame.

Finally, at long last, the 1982 season promised to be different. The Braves won the first 13 games coming out of the gate that season and the sky seemed the limit. In typical Braves fashion, however, they played .500 ball for the remaining 149 games, including losing 11 in a row and 15 out of 16 at one point coming down the stretch, and held on by their fingernails to win the National League West by one game over the Dodgers. They got swept by the Cardinals in three games in the NLCS.

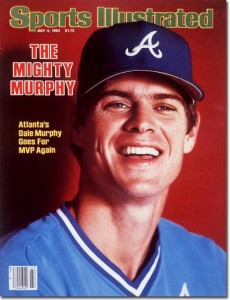

The one bright spot in those dreadful years, besides Aaron and Niekro, was # 3, Dale Murphy. Murph was and still is one of the classiest guys who ever put on a baseball uniform, a role model for any young person watching and trying to learn the right way to play the game. Murph made his debut as a catcher, playing 19 games in the ’76 season, before moving to first base and then finally center field. He won back-to-back league MVP awards in ’82 and ’83 and finished his career two homers shy of 400. The fact that he’s not in Cooperstown is a travesty. He proudly represented the team and the city for 15 seasons before they traded him to the Phillies in the middle of the 1990 season.

The one bright spot in those dreadful years, besides Aaron and Niekro, was # 3, Dale Murphy. Murph was and still is one of the classiest guys who ever put on a baseball uniform, a role model for any young person watching and trying to learn the right way to play the game. Murph made his debut as a catcher, playing 19 games in the ’76 season, before moving to first base and then finally center field. He won back-to-back league MVP awards in ’82 and ’83 and finished his career two homers shy of 400. The fact that he’s not in Cooperstown is a travesty. He proudly represented the team and the city for 15 seasons before they traded him to the Phillies in the middle of the 1990 season.

Everything changed for the Braves in 1991, with the arrival of Terry Pendleton, Sid Bream, Rafael Belliard, closer Juan Berenguer (“Señor Smoke/El Gasolino”) and the return of Bobby Cox  in his first full season of his second-go-round as Braves manager. The Braves run of 14 consecutive division titles, five National League pennants, and a World Series championship was the fulfillment of what we all dreamed about during all those dismal years before.

in his first full season of his second-go-round as Braves manager. The Braves run of 14 consecutive division titles, five National League pennants, and a World Series championship was the fulfillment of what we all dreamed about during all those dismal years before.

If the Atlanta Stadium years represent one chapter of the Braves, the Turner Field years represent another (though there is some overlap in terms of division and league championships), and now that chapter is coming to a close too. The Braves will move away from their home of 50 years (geographically speaking) when the 2016 season ends, and head north to play in Cobb County, hoping the fans follow with them. That seems to be open to debate at this point.

And what will the new stadium be named? The Braves say they will sell the naming rights, so it won’t be named for Hank Aaron, Phil Niekro, or Dale Murphy, though it should be. Aaron-Niekro-Murphy Stadium has a nice ring to it, and it would be a fitting tribute to three giants of the game, men of class and integrity who played the game the way it was meant to be played and who made following the Braves in those long-ago summers worth every bit of the anguish and heartbreak of losing all those games.  Incidentally, the broadcast booth of the new stadium should be name for Skip Carey, Pete Van Wieren, and Ernie Johnson, the radio and TV voices who journeyed with us all the way, and who made it all seem like fun no matter the score.

Incidentally, the broadcast booth of the new stadium should be name for Skip Carey, Pete Van Wieren, and Ernie Johnson, the radio and TV voices who journeyed with us all the way, and who made it all seem like fun no matter the score.

When the Braves leave downtown Atlanta, something of lasting value will be lost that can’t be tallied up in the won-loss column or in a box score. The memories—and the ghosts—of Capitol Avenue will linger on in the hearts of one Braves fan at least long after the last game at Turner Field is over and the stadium has returned to dust. Hail and farewell. Game called.

Game Called, by Grantland Rice–1956 version

Game Called. Across the field of play

the dusk has come, the hour is late.

The fight is done and lost or won,

the player files out through the gate.

The tumult dies, the cheer is hushed,

the stands are bare, the park is still.

But through the night there shines the light,

home beyond the silent hill.

Game Called. Where in the golden light

the bugle rolled the reveille.

The shadows creep where night falls deep,

and taps has called the end of play.

The game is done, the score is in,

the final cheer and jeer have passed.

But in the night, beyond the fight,

the player finds his rest at last.

Game Called. Upon the field of life

the darkness gathers far and wide,

the dream is done, the score is spun

that stands forever in the guide.

Nor victory, nor yet defeat

is chalked against the players name.

But down the roll, the final scroll,

shows only how he played the game.